- Author

- Ranina Sanglap Gaurav Raghuvanshi

- Theme

- Banking

Many Indian nonbanking financial companies may remain short of funds as investors become more cautious and the economy contracts, adding risks to the broader financial system.

Indian authorities have recently stepped up efforts to improve liquidity for nonbanking financial companies, or NBFCs, as the coronavirus pandemic halted the economy for several weeks, adding strain on the nonbank lending sector that was already hit by a funding squeeze after a few high-profile defaults. Now, as the wheels of the world’s fifth-biggest economy begin to turn again, analysts doubt whether the smaller and weaker NBFCs will still find favor.

The government announced a 300 billion rupee special liquidity window for NBFCs and a partial credit guarantee program of up to 450 billion rupees of their loans. The Reserve Bank of India slashed interest rates, allowed a six-month moratorium on payments by borrowers, relaxed rules for recognizing nonperforming loans and a special three-year repurchase operation aimed directly at providing loans to NBFCs.

Devil in the details

“While the intent is good, the devil is in the details,” said Nirmal Jain, chairman of retail-focused NBFC IIFL Finance Ltd., in comments emailed to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The government’s plan to buy NBFCs’ bonds of up to 300 billion rupees can be via primary or secondary purchases. “In practice, mutual funds will get rid of their NBFC bonds by selling to banks under this scheme. … The net effect is the government taking over risk from mutual funds for decisions taken even before the crisis, and funds do not go to the NBFCs,” Jain said.

Indian NBFCs were seen as a beacon of financial inclusion and economic growth. But they became a major source of systemic risk since mid-2018 after scandals and defaults by several large players such as Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services Ltd., Dewan Housing Finance Corp. Ltd. and Reliance Capital Ltd.

The perception of NBFCs ranges between some who view them as “doing an altruistic job of delivering credit to the underprivileged, underserved segments of society,” while others “view them as an avoidable annoyance, with questionable governance, posing threats to the financial system’s stability,” Jain said.

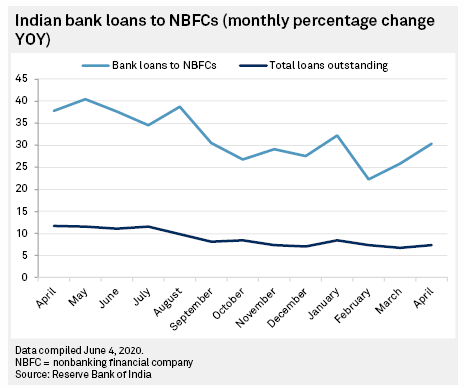

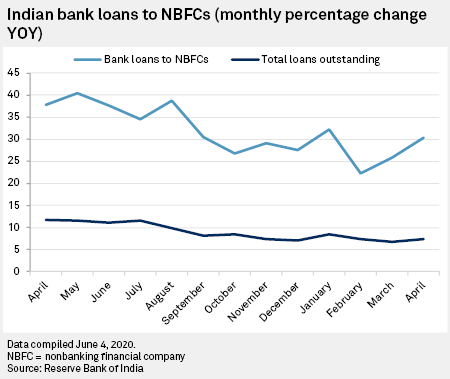

Banks have been the only major source of funds for Indian NBFCs in recent months as other avenues such as mutual funds and external commercial borrowings have reduced significantly.

Mutual funds’ exposure to NBFCs has almost halved over the past 18 months, falling to 18% of debt assets under management in April 2020, from 34% in September 2018, Credit Suisse said in a May 26 note.

“Mutual funds have been aggressive in reducing exposure to perceived weaker NBFCs,” Credit Suisse said, noting that they have almost completely pulled funding to such players in the last 1.5 years.

The “long tail” of the previous corporate nonperforming loans cycle over 2016-2019 had already led to a lending concentration around well-rated players. However, it has been further accentuated in the last 12 months with most large players in the segment giving more than 90% of their incremental credit to only the well-rated entities, Credit Suisse said.

“Banks are unlikely to add incremental credit risks to balance sheets in the current uncertainty and to continue to chase improvement in the rating mix of their existing corporate portfolios,” it said.

Long and short

The inherent problem with Indian NBFCs is that they “borrow short and lend long,” said Hemindra Hazari, an independent analyst based in Mumbai. Moreover, Indian NBFCs’ problems are not just liquidity or asset and liability management. Often, it can be a solvency issue as a lot of their lending has been problematic, Hazari said in a phone interview with S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The solution for NBFCs is to contract their books and raise equity, Hazari said. The banking system is unwilling to lend and promoters have been reluctant to bring in fresh equity. And yet, the NBFCs are affected as production has been lost. The government’s fiscal measures to stimulate the economy so far have been inadequate, Hazari said.

The moratorium by banks to NBFCs on loan repayments is the only “meaningful relief” for them to withstand the liquidity stress, Moody’s said June 1. However, it is not clear whether all NBFCs will benefit from the moratorium as banks will likely decide on a case-by-case basis, it said. Also, the moratorium on repayments “does not address the structural access to funding issues of NBFCs,” it said.

An added complication is that the moratorium is also available to the NBFCs’ clients, which has led to declines in their inflows, choking off a primary source of debt repayments, Moody’s said.

“It is a situation where a water tank, however strong, has its inlet closed and outlet open. Currently, only banks are flush with liquidity and in a position to provide fresh credit,” IIFL’s Jain said.

It is the smaller and weaker NBFCs that are mainly facing the liquidity crunch, said Jayesh Kumar, chief economist at Manappuram Finance Ltd. “The challenge is two-faced. One, to ensure NBFCs don’t go belly up for lack of liquidity and to get the credit cycle restarted. Addressing just one of them would not be enough.”

Narrow window

The Finance Industry Development Council, a lobby group for Indian NBFCs, said the window of the government’s relief measures is too small. The special liquidity plan is available only for three months and may provide relief to existing holders of short-term NBFC debt instruments, without translating in additional cash flow to the sector.

It may not encourage NBFCs to lend to the medium- and small-scale borrowers. Any NBFC availing of funds under the plan “may in fact, end up in disturbing its asset-liability matching,” the Finance Industry Development Council said May 20. It wants the liquidity program to run for three years. The FIDC has also sought an extension of the government’s guarantee plan to cover loans or instruments with a residual maturity of three years, from less than one year offered at present.

However, not all may be lost, according to Sameer Narang, chief economist at state-run Bank of Baroda. In the past, after every credit shock, it usually took six to nine months for normalcy to return. As the economy reopens, many NBFC customers will resume payments, he said.

“It has to be a step-by-step process. The first step is to ensure liquidity, so that credit is available. Then, demand needs to be created, and demand will automatically get created once the economy opens up,” Narang said.

Some increase in defaults is to be expected, but as economic activity resumes, the NBFCs’ customers will get cashflows and that will be used for repayments, Narang said. “You may come out of this quite alright.”

As of June 8, US$1 was equivalent to 75.48 Indian rupees.