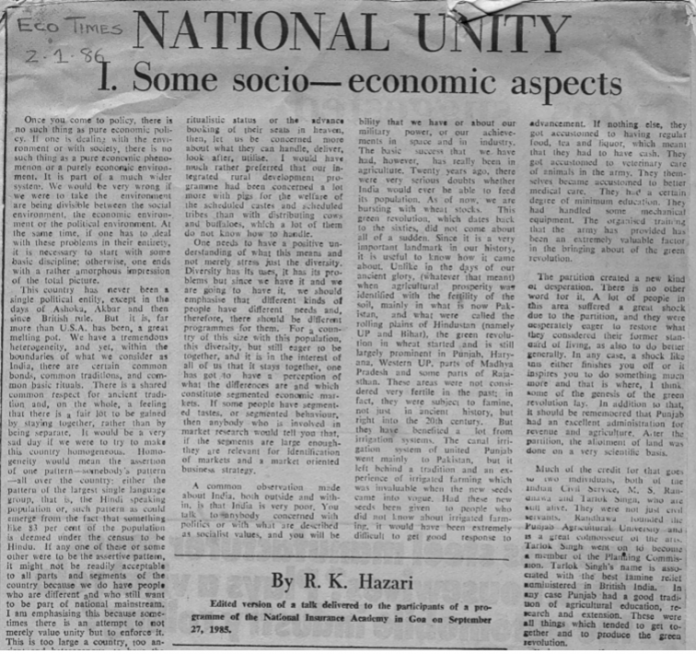

Edited version of a talk delivered to the participants of the National Insurance Academy in Goa in September 27, 1985.

I. Some socio—economic aspects

Once you come to policy, there is no such thing as pure economic policy. If one is dealing with the environment or with society, there is no such thing as a pure economic phenomenon or a purely economic environment. It is part of a much wider system. We would be very wrong if we were to take the environment are being divisible between the social environment the economic environment or the political environment. At the same time, if one has to deal with these problems in their entirety, it is necessary to start with some basic discipline; otherwise, one ends with a rather amorphous impression of the total picture.

This country has never been a single political entity, except in the days of Ashoka, Akbar and then since British rule. But it is, far more than U.S.A. has been, a great melting pot. We have a tremendous heterogeneity, and yet, within the boundaries of what we consider as India, there are certain common bonds, common traditions, and common basic rituals. There is a shared common respect for ancient tradition and, on the whole, a feeling that there is a fair lot to be gained by slaying together, rather than by being separate. It would be a very sad day if we were to try to make this country homogeneous. Homogeneity would mean the assertion of one pattern—somebody’s pattern —all over the country, either the pattern of the largest single language group, that is, the Hindi speaking population or, such pattern as could emerge from the fact that something like 83 per cent of the population is deemed under the census to be Hindu. If any one of these or some other were to be the assertive pattern, it might not be readily acceptable to all parts and segments of the country because we do have people who are different and who still want to be part of national mainstream. I am emphasising this because sometimes there is an attempt to not merely value unity but to enforce it. This is too large a country, too ancient and heterogenous, to have the kind of unity or homogeneity that, we believe, has been achieved in U.S.S.R. or in China or in Japan.

We speak a wide variety of languages and there is often much more in common between people who come from one part of the country regardless of which religion or whatever they belong to, and people from a different part of the country where the religion might be the same but the languages or the customs are very different. To give an example, there are many people who go abroad from India and say that we Indians are vegetarians. This is not true even of all the Brahmins in the country – many Brahmins take meat or fish or both. If you take the most vegetarian state in this country, namely, Gujarat, I would request you to remember that a large part of the population of Gujarat itself is tribal and is, therefore, not vegetarian. There is a fairly large part which is scheduled caste and not vegetarian. A fairly large proportion is Muslim and not vegetarian. A fairly large proportion, one of the highest in the country, probably the highest, is Rajput and not vegetarian. One cannot identify what you might call the Indian ethos with any particular type of behavior or system of thinking and action.

I have known some Indians abroad who express horror that the Chinese love to eat pigs and dogs. I wonder how many of you are aware that this is true in many parts of India too. The Nagas love dogs; stuffed dog is a delicacy for them. Similarly, pigs are the favoured food not only among the tribal of the North East; they are also the favoured meat of nearly all the scheduled castes nearly all over India. I wish the government had been more conscious of this fact in some of its development programmes, it is no use giving cows and buffaloes to people who like to eat pigs. If you are concerned with their welfare rather than their ritualistic status or the advance booking of their seats in heaven, then, let us be concerned more about what they can handle, deliver, look after, utilise. I would have much rather preferred that our integrated rural development programme had been concerned a lot more with pigs for the welfare of the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes than with distributing cows and buffaloes, which a lot of them do not know how to handle.

One needs to have a positive understanding of what this means and not merely stress just the diversity. Diversity has its uses it has its problems but since we have it and we are going to have it, we should emphasise that different kinds of people have different needs and, therefore, there should be different programmes for them. For a country of this size with this population, this diversity, but still eager to be together, and it is in the interest of all of us that it stays together, one has got to have a perception of what the differences arc and which constitute segmented economic markets. If some people have segmented tastes, or segmented behaviour, then anybody who is involved in market research would tell you that, if the segments are large enough-they are relevant for identification of markets and a market oriented business strategy.

A common observation made about India, both outside and within, is that India is very poor. You talk to anybody concerned with politics or with what are described as socialist values, and you will be reminded in no time that, may be 50 per cent or 40 per cent of the population is below the poverty line. What is the poverty line? It has been defined in India as approximately Rs. 65 per head per month al 1978 prices and in terms of calories about 2,000 calories per day. This is a dismally low level. You compare this with the definition of the poverty line in the US, where it is about $10,000 of so per family per year. But I would also request you to appreciate that, by this very distinction, about half of the population is above the poverty line. It is a question of describing a glass as half-empty or half-full. Most market research analysts have indicated that out of the population of 700 million, approximately 100 million have purchasing power that would equal the purchasing power of any rich country in the world. This is not a market size that you can regard as small. One can get into quantification problems. One can look into consumer behaviour, saving behaviour, and what not. All that I am saying is that the extent of poverty in this country should not blind us to the fact that we also have a very large market. We have large segments of the population whose purchasing power is very large and, therefore, this is a country in which you can do a fair lot of business. This is of relevance not just for foreign investment (of which we. have very little, rightly or wrongly) but also as a basic indicator for domestic investment as well as for domestic marketing.

Let me get on to something which is very closely allied with technology, with certain historical developments, with certain geographical aspects. The greatest success that we have had since independence has been in agriculture, though every visiting foreigner asks or, when an Indian visits abroad, he is asked, about the nuclear capability that we have or about our military power, or our achievements in space and in industry. The basic success that we have had, however, has really been in agriculture. Twenty years ago, there were very serious doubts whether India would ever be able to feed its population. As of now, we are bursting with wheat stocks. This green revolution, which dates back to the sixties, did not come about all of a sudden. Since it is a very important landmark in our history, it is useful to know how it came about. Unlike in the days of our ancient glory, (whatever that meant) when agricultural prosperity was identified with the fertility of the soil, mainly in what is now Pakistan, and what were called the rolling plains of Hindustan (namely UP and Bihar), the green revolution in wheat started and is still largely prominent in Punjab, Haryana, western UP, parts of Madhya Pradesh and some parts of Rajasthan. These areas were not considered very fertile in the past; in fact, they were subject to famine, not just in ancient history, but right into the 20th century. But they have benefited a lot from irrigation systems. The canal irrigation system of united Punjab went mainly to Pakistan, but it left behind a tradition and an experience of irrigated farming which was invaluable when the new seeds came into vogue. Had these new seeds been given to people who did not know about irrigated farming, it would have been extremely difficult to get good response to the fruits of new research. Fortunately, these came to farmers who had rich experience, first in canal irrigation and, subsequently, also in tube-well irrigation.

These are also the areas where there has been a tradition of military service. You might ask me what is the connection between military service and the technological break-through in agriculture. I think they are closely interrelated. It has nothing to do with martial races or merely ethnic qualities. Please remember that the Bengal Army of the East India Company and even much of the Bombay Army was recruited till 1857 largely from UP (Hindustanis as they were called), particularly Brahmins. It has, however, a lot to do with the fact that when you have military recruitment and military training of a large number of people from a certain area, people get acquainted with new goods and new needs. They are more willing to accept a new discipline and they learn to do many things as an organisation. They react, therefore, not just as individuals but as organised bodies of men.

What is more, it gives a secure cash income while the people are in service and a cash pension when they retire. Some of us have forgotten what it means to have cash in hand because cash is now far more freely available. I remember as a child in the 1930’s and the 1940’s what it meant to have cash. It was quite scarce. You might say money had value then and has very little value now but, leaving that aside, I have known people get a pension of three rupees to five rupees a month; and what a difference it used to make to their families in the Punjab. It also meant that people had travelled to different parts of the country and the world and, therefore, their eyes had opened to the possibilities of advancement. If nothing else, they got accustomed to having regular food, tea and liquor, which meant that they had to have cash. They got accustomed to veterinary care of animals in the army. They themselves became accustomed to better medical care. They had a certain degree of minimum education, have handled some mechanical equipment. The organised training that the army has provided has been an extremely valuable factor in the bringing about of the green revolution.

The partition created a new kind of desperation. There is no other word for it. A lot of people in this area suffered a great shock due to the partition, and they were desperately eager to restore what they considered their former standard of living, as also to do better generally. In any case, a shock like this either finishes you off or it inspires you to do something much more and that is where, I think, some of the genesis of the green revolution lay. In addition to that, it should be remembered that Punjab had an excellent administration for revenue and agriculture. After the partition, the allotment of land was done on a very scientific basis. Much of the credit for that goes two individuals, both of the Indian Civil Service, M. S. Randhawa and Tarlok Singh, who are still alive. They were not just civil servants. Randhawa founded the Punjab Agricultural University and is a real connoisseur, of the arts. Tarlok Singh; went on to become member of the Planning Commission. Tarlok Singh’s name is associated with the best famine relief administered in British India. In any case Punjab had a good tradition of agricultural education, research and extension. These were things which tended to get together and to produce the green revolution.

It is not as if these conditions have not been or cannot be reproduced elsewhere you can see the achievements in some other parts of the country. You take coastal Andhra their achievement in rice has been remarkable. You take rice production in Thanjavur district of Tamil Nadu, it has been remarkable. These are all areas where irrigation has been extremely good, where educational levels are fairly high, where the government administration has been good for law and order and for irrigation. Please remember irrigation depends a lot upon the government, not only canal irrigation but even well irrigation. What has distinguished coastal Andhra and Thanjavur from Punjab has been that, on the whole, in Punjab due to land reforms as well as various other factors, the distribution of land is on the whole far more equitable than it has been In Andhra or Thanjavur.

Let me deal with two points that rise out of the green revolution which are often commented upon adversely. There are some people who damn the green revolution because it has made the “lower” classes uppity. This is fundamental to economic growth, whether the people concerned are scheduled castes or not, and whether they are local people or imported labour. You will find that when people are terribly poor, they cannot rebel and they cannot agitate. In our last great famine in Bengal in 1943-44, 3.5 million persons died of hunger. Not a single food shop was looted. That cannot happen now. For one thing, there is no question of any large number of people dying of famine. Our last bad crop was in 1980 and yet nobody died of famine. For another, when people have their stomachs reasonably full, and when they are somewhat better dressed than before, and they also know that they have the right to vote and that they also have the right to watch T V, then they are going to agitate, because they will have aspirations and they will like those aspirations to be fulfilled. If they were absolutely hungry, they would not have the energy to agitate. They would not have the energy to promote their interests. When their stomachs are reasonably full, they have the energy to agitate and they are conscious of their rights. They are bound to be uppity.

A second aspect is that, in India, developmental tensions accentuate class-cum-caste problems. The rich have, of course, become richer but the poor have not become poorer, they are becoming less poor. The point is very often raised that there are few castes that have benefited from this process. Now leave aside Brahmins, whose importance is primarily in terms of ritualistic status, or because they have a disproportionate importance in administration and in the professional classes, and who, therefore, stand to benefit disproportionately from the bureaucratic expansion (both governmental and commercial) which is a common feature of a control-state. The importance of the Kshatriyas was greatly reduced after the abolition of zamindari and the privy purses; they are recovering some of their earlier importance, partly because of their renewed interest in agriculture, partly because of the new political balancing of forces. The Baniyas have always been economically important. Please remember that none of the three higher castes is numerically important. When you have a universal right to vote. It is not enough to have just economic importance. You have also got to have enough votes. When it comes to the number of those who vote, it is the so-called lower castes that are of predominant importance, because they would constitute more than three-fourths of the Hindu population. Since the caste system is found among the other communities also, you can take it mat they account for roughly three-fourths of the total population too.

The tensions in the South which marked the anti-Brahmin movement have almost disappeared there now, because while the Brahmin might still be part of the non-Brahmin consciousness, he is not that material or important there any more. The tensions and the conflicts that matter are those on the ground between different sections of the farming community, and between the farm owning communities and those who work without owning the land. At this level, the tensions are violent with no holds barred. You see this phenomenon, for instance, in the North west between the Jat and the Chamar, in the South between the Nadars, Mudaliars and the Palayas, in the Fast between the Bhumihar Yadav and the Chamar. Within the fold of the green revolutionaries, in Haryana, you see it between the Jat, the Ahir and the Bishnoi. Accompanying these is the tensions between the small and large farmers, the dry and the wet farmers, and between those with rival claims to water. Participation in the green revolution has become one of the instruments of acquiring power. There is rivalry in politics, in administration and in cooperative and educational institutions.

While it is a positive achievement to have better economic performance, please remember that there is also a cost, and that cost is not just deficit financing and inflation, it is not just your foreign indebtedness. There is conflict, tension and violence. There was a time when people of the lower castes never attacked or counter-attacked people of the higher castes. That is not so any more. It was taken as normal in the olden days for people of the higher income or higher status groups to take away the lands or women of the people lower down. When you try to do this now, it is resisted. And you get not only violence but an explosive potential for violence. This is what I would regard as the cost of the green revolution. This is an inevitable cost. The green revolution is a great success story because the benefits outweigh the costs. The outcome will not be smooth, painless, quiet, non-violent process. There is no such thing. This country is not a non-violent country nor are the people non-violent. That is why I started by talking about vegetarianism: we have too many false notions about ourselves.

Social and sectional violence is not a new phenomenon. At the risk of committing blasphemy, let me start with the Epics. What are the two famous Hindu Epics about? Do they not portray violence from the beginning till the end? There is violence within and between families. There is violence against women, violence of the dominant Aryas against the Rakshasas. There is violence of the superior castes over the inferior castes. The Hindus have a holy book, it is the Gita. Where was it recited? What was the occasion for it? It was a violent struggle between cousins. What happened on the battlefield as a result of that battle? Entire communities were destroyed — ostensibly for the victory of righteousness. If you think that all are sagas of mythology, take the major recorded history of what is described in text books as the Hindu period: Kalhana’s Rajtaranpani is the history of Kashmir upto roughly 1100 A.D. It is again a history of violence of every kind, of civil wars, of wars against neighbours, burning of holy shrines, melting of precious idols for their bullion, oppression of the Brahmins and the Buddhist monks, of atrocities against women. The greatest oppression of the Brahmins of Kashmir was done by Hindus.

II. Green revolution

I am not saying that India was a picture of violence unalleyed. All that I am saying is that violence has been and is part of our ethos. Violence is an integral part of our history and life — just as sex is. The green revolution is giving it an economic base which is positive as compared with the impoverishment and misrule which spawned the infamous Pindaric, Thugs and dacoits of Central India. You might ask, then why the green revolution has not made adequate headway elsewhere, particularly in the areas east of Lucknow. Mind you this is changing, though Bihar and Orissa are still pretty bad in agriculture. During the last ten years, there has been a fair lot of growth of irrigation, of new seeds and of marketing in Central and Eastern U.P. At one time, it almost appeared that, after the introduction of bamboo tube-wells in North West Bihar, there would be a major change there also especially in the old districts of Cbamparan and Saran, unfortunately, this trend leveled off around the mid-seventies. The trends during the last five years in eastern U.P. have been most encouraging.

Outputs

I am saying this not on the basis of the inputs “distributed” but on the basis of the outputs. The statistics indicate more wells dug, more fertilizer consumption, as also much higher food procurement. This is also supported by the sales data of the companies that sell consume: goods in these areas. The green revolution has definitely spread to Eastern U.P. I hope it spreads more. It is still not comparable with Punjab, not at all. But once it gets going in Ganga valley, it will be a lot cheaper than the green revolution in Punjab. The wage rates are lower, the land is more fertile, and there is not the same need for initial pioneering investment and the learning cost.

Even in West Bengal, till the mid-seventies, that is to say,” roughly between 1970 and 1976, there were hopeful signs that the green revolution would make headway. There was a fair lot of experimentation in agricultural research and extension, especially in evolving new strains of paddy suitable for additional crops. Bengal has been a producer of wheat for quite sometime and there is a second rice crop and a third rice crop in many districts. Unfortunately, all this tended to level off after 1976, due to a variety of reasons, which I will not go into, except to stress that the reasons are not that we cannot evolve new seeds or that the Bengalis don’t work. These things require direction and political and administrative motivation. They require good politics, or at least for positive political direction.

The slow pace of development in the Eastern region is a very important question that must be tackled because this large part of the country cannot be left to languish without endangering the whole country. Somehow in our consciousness, we have been much more concerned about the divide between the north and the south, than the divide between the rest of the -country and the eastern region. This divide is a lot more important than has been realized. This was so even in ancient times. Much of what is called Indian history is really the history of north India. Southern history was really tagged on to, it as part of the effort for the cultural integration of Hindudom, especially after the 6th century A.D. This is, I concede a matter of historical dispute and debate. What is beyond dispute is that much of the Eastern region was not really part of Aryavarta or Hindustan, as those terms were generally understood.

The eastern boundary of Aryavarta, i.e., Ancient Hindu North India was at Varanasi. Any orthodox Hindu who went to the east of Varanasi had to say his last prayers before leaving and, if he returned alive, he had to get purified after return. Why? Because the lands to the east of Varanasi were full of what were described as rakshasas, malechhas, heretics, blasphemers and the like (including the heretical Buddhists and Jains). The integration of this region that was coming about between the 7th and the 11th centuries A.D. was disrupted by what is described as the Islamic invasion, which was nothing more than a Turko-Afghan invasion, reinforced by an egalitarian message, supported with fast cavalry and ritually impure gunpowder.

Muslim conquest

If you leave aside the loot-raid of Mahmud Ghaznavi and Mohammed Ghori, the real so-called Muslim conquest was by the Khiljis around the end of the 12th century. In less than two decades the armies of Khilji marched triumphantly from Delhi to Mathura and from Bhatinda to Dhaka. As Prof. Habib, the Alligarh historian has asserted, this was not so much a conquest by Islam or its conquering sword. No sword or cavalry can move that fast successfully. It could come about only because the social structure was so rotten that the invading armies were welcomed as liberators by many sections of the population. They had no stake in the state or the society of that time. Or, take a more recent example within our living memory. In 1971, the Indian army could not have liberated Bangladesh by the force of arms alone within a fortnight of hostilities. Had it encountered a hostile population in Bangladesh, why the Indian army, all the armies of the world would have sunk in the silt of the Ganga in Bangladesh. It is one of the most difficult terrains in the world, if you have to fight for every inch.

What I am stressing is that this kind of alienation from the mainstream that large groups of people come to feel is a dangerous thing. I am not saying that people in the eastern region would secede from the country or anything like that. If any large set of people feel rightly or wrongly, that they are being ignored, or slighted by the larger community or that they are not accepted as an integral part of the community, then, whether you get internal problems or you get border problems, you have difficulties, in the eastern region, we have not only poverty and backwardness, we have much more ethnic diversity than most of us have realised. There are ethnic problems not merely in the tribal north east, but also in south Bihar, in Orissa, and even in West Bengal.

This divide is more intense than the familiar one between the north and the south, which was somehow bridged over many centuries by the establishment of a common Hindu orthodox tradition and, in more recent years, by a quicker pace of economic and educational development in the peninsula. A large part of the population of the eastern region is either Mongoloid or Austroloid. The bulk of them may be classified as Hindus in the Census, but they are ethnically distinguishable from the mainstream. A conscious and concerted effort is required to integrate them.

You have to go to Bihar to find out what unproductive land ownership can mean. Land is unequally owned even in Coastal Andhra, but the large Andhra farmers are known at least for their high productivity. There has been no land reform worth the name in Bihar. The large land owners have, in general, participated little in the green revolution. Floods are an annual or bi-annual occurrence in most parts of the eastern region; they might renew the fertility of the soil but they discourage permanent improvement of the land. There has been little attention to the promotion of rabi cultivation which could be relatively safe against floods or, for that matter, to the improvement and maintenance of transport and marketing facilities. The old handicraft industries of the eastern region were undermined long ago. Most of the industries that were set up under British auspices got into trouble from the mid-sixties when the plan holiday started. Jute textiles have suffered even more than cotton mills. Much of the recent expansion in coal has been outside Bengal and Bihar. Tea has, on the whole, done well in the last ten years but almost no new industry has been going to the eastern region for a variety of reasons.

Eastern region

I think it would be very sad if we were to neglect the problems of the eastern region any longer. Let me take you back a little into some post-independence history. Why was a deliberate attempt made to locate so many new public sector industrial units in Bangalore and later in Hyderabad? Why were uniform prices and tariffs fixed; for coal and steel? Why was so much encouragement given, partly, for commercial reasons but also for political reasons, to the development of Bombay? Why were two oil refineries located in Bombay in the early fifties? Why was Madras, under Rajaji and the Chief Ministers who followed him, allowed to run “productive” overdrafts on the Reserve Bank long before the practice caught on in all the states? Apart from security considerations of developing new facilities well away from the borders, there was quiet rightly a feeling that the peninsula should not feel alienated from the politically dominant north The peninsula had to be made to feel that it could enjoy large benefits from being an integral part of the country. I think this effort was worthwhile. You can keep different parts of the country together by being deliberately generous in the treatment of areas and segments that otherwise might feel that they are not an integral part of the community. This treatment requires to be extended to the eastern region. It is ethnicallv different and, at the extremes, it has been exposed a lot more to the army and the police than to the more positive economic aspects of post-independence Indian administration.

Professional persons are few in number but they have a strong vested interest in the unity of the country, because their business and their promotional prospects depend upon having large and expanding markets all over the country.

In olden days what unity there was in the concept of India rested largely upon the common Brahmin tradition, which could enjoy sanctity and acceptance only when the social structure was explicitly inegalitarian. Political unity was hardly relevant then. Now that it is of paramount and perennial importance. One needs strengthening of cementing factors and forces, so that there may be continued vested interest in keeping the country together. The green revolutionaries who have contributed so much to economic achievement do not-need to have the same compulsive interest in national unity as the professional classes have: their interests are restricted either to a particular district or to a particular crop: that does not make the farmers less patriotic, it is just that their interests are more sectional.

Loyalties

In a federal society (I am not talking about a federal state or federal constitution), one must explicitly recognise sectional loyalties to ones’ state or ones’ association, or one’s religion or one’s ethnic kinship group, provided all these are subordinate to one’s paramount loyalty to the country as a whole. In the army, all ranks are fiercely proud of their regiments and their battle slogans; that does not mean (that they are disloyal to the army as a whole, far from it. At the same time, one has to strengthen those elements whose own sectional vested interests hinge explicitly and directly upon the unity of the national market. This is what I see as the key political role of the professional classes, few though they are in numbers, as distinct from the skills that they contribute.