Sucheta Dalal

22 April 2021

On 10th April, The Times of India published a report to say that major banks, including State Bank of India (SBI), Bank of Baroda, Bank of India and HDFC Bank, had moved the Supreme Court (SC) of India to recall its six-year old judgement of 2015, which had ordered banks to provide certain information about their functioning under the Right to Information (RTI) Act. Banks and their expensive lawyers argued that “account holders may sue them for putting such details (client information) in the public domain” and that the order could be “misused for corporate rivalry” and affect the banking industry as a whole. Let’s examine how correct this claim is.

We have reported extensively on the SC’s path-breaking judgement of 2015 which decided on 11 orders of the central information commission (CIC) of which 10 were passed by Shailesh Gandhi. The judgement, while dismissing the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) objection to share inspection reports, had observed, “By attaching an additional ‘fiduciary’ label to the statutory duty, the regulatory authorities have intentionally or unintentionally created an in terrorem effect.”

This should have put an end to the long struggle for to get information from banks, which begun in 2010-11. But banks are ensuring there is no end to this war to block access to information. On 20th April, Moneylife Foundation organised a webinar to understand the latest attempt by banks to avoid disclosure and transparency by seeking a recall of the path-breaking 2015 judgement. Prashant Bhushan, renowned senior counsel in the Supreme Court, who has waged a pro bono battle on behalf of ordinary citizens, explained the situation.

Extraordinary as it may seem, regulators are not overly concerned about the apex court’s judgements on this issue. Instead of complying with the judgement, RBI issued a circular telling banks about various kinds of information that could still be denied. So, contempt petitions were filed in 2016 leading to a decision in April 2019 which warned RBI to comply with its orders. All of this was happening in full public glare and was regularly reported in the media, but banks did not see it fit to intervene in the matter, said Mr Bhushan. They did not even react to the contempt petition. It is only after this that banks began to file miscellaneous applications in an already decided case, arguing that they had not been heard on the matter. Mr Bhushan points out that a banker-borrower relationship is not like that of a lawyer-client or doctor-patient and a host of SC judgements have emphatically upheld people’s right to know what public officials are doing when there is over-riding public interest involved. He has also argued in this matter that banks cannot file miscellaneous applications to seek a backdoor review of a decided matter; a decision on this is expected shortly. But even if activists win this round, banks are likely to file a review petition and continue to fight, since the regulator is backing them and the finance ministry chooses to remain silent about RTI matters. Fortunately, a couple of intrepid RTI activists, such as Girish Mittal (one of the original petitioners) and Pune-based Vivek Velankar, managed to obtain key inspection reports that already reveal how RBI and banks plan to respond to RTI requests. Girish Mittal received inspection reports of six banks—HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, SBI, Axis Bank, Punjab and Maharashtra Cooperative Bank (PMC Bank) and City Cooperative Bank– for three consecutive years from 2013-2015. All reports, including their analysis, are available on the Moneylife website. Here’s what the reports reveal.

No Disclosures: For starters, RBI has ensured that absolutely no personal information was provided to Girish Mittal. The reports are heavily redacted to remove every single bit of personal information from all of them. So the claim by banks’ high-powered lawyers that banks’ clients could sue them for sharing confidential information is both untrue and deceitful.

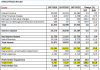

Vivek Velankar sought information on large bank defaulters (over Rs100 crore) and the amounts recovered by the banks after the write-off. This information has already been put in the public domain by bank unions. And, yet, only 10 banks provided the information he sought. These too have been analysed (https://www.moneylife.in/tags/bankloot.html) by us. They revealed that 12 nationalised banks wrote off Rs6.32 lakh crores in eight years and recovered just 7% from wilful defaulters. This exposed the false claim by the finance ministry and its high-profile consultants that banks continue to pursue defaulters and recover money written off.

Double Standards: Activist Subhash Chandra Agarwal and former central information commissioner (CIC) Prof Sridhar Acharayalu both unmasked the questionable claim about banks protecting the privacy of borrowers. Mr Agarwal pointed out how banks have no concern about the privacy of smaller defaulters. SBI routinely publishes advertisements naming borrowers and amounts owed as part of the recovery policy of shaming them. Prof Acharayalu said that, in one case in Andhra Pradesh, a borrower, unable to bear the ignominy, resorted to suicide. And, yet, the banks claim exactly the opposite in court, about fiduciary information. Prof Acharayalu said, refusal to provide information after an unequivocal apex court judgement amounts to contempt and it is surprising that the SC has allowed this to continue.

Poor Investigation Framework: A bigger issue is the fact that India has no mechanism for regulators, policy-makers and bureaucrats to be publicly held to account, like the televised Senate hearings of the US. RBI’s inspection reports made available to us, for the first time, exposed the outdated inspection framework, perfunctory process, lack of follow-up to ensure compliance with findings and observations of previous inspections. All four experts who analysed the reports shared this view. For instance, HDFC Bank used to win awards for technology until repeated failures of its digital systems unleashed so much public anger that RBI finally cracked the whip in December 2020 asking it to stop on-boarding new customers until it fixed its systems. RBI’s inspections are not geared to look at these issues, although a large chunk of operations are now through online transactions. In PMC Bank, RBI inspectors kept harping about tardy allocation of unique identification numbers (UIN) but there was no follow-up. This was disastrous, because top management, in cahoots with the Wadhawans of Housing Development and Infrastructure Ltd (HDIL), opened 21,000 fake accounts that were kept out of the core banking system to funnel out dubious loans that destroyed the Bank. RBI’s own officials have lost Rs200 crore in the PMC Bank collapse. The inspection framework has no capability to catch software manipulation, as was done by both branches of the Wadhawan family (DHFL and HDIL) to loot thousands of crores of rupees. Both entities operated under RBI regulation.  Until the reports were put in the public domain, nobody knew why bank supervision was so poor and inspections a failure.

Until the reports were put in the public domain, nobody knew why bank supervision was so poor and inspections a failure.

Well-known banking analyst, Hemindra Hazari, said that even these perfunctory reports have a wealth of information. For instance, while bank annual reports tend to glorify themselves, it is RBI inspection that revealed poor and deteriorating internal audit rating for HDFC Bank, which is India’s most valuable bank. It also showed the absence of any follow-up or action by the RBI, despite the deterioration. The lack of commercial banking experience on Axis Bank’s board was completely ignored by RBI inspection, although this was the “elephant in the board room,” says Mr Hazari. Was the board capable of evaluating lending decisions?  Rajendra Ganatra, a former banker, and R Balakrishnan, with vast research and fund management expertise, also pointed to superficial inspection, lack of follow-up and the lack of interest in setting things right in both the inspection reports analysed by them (Axis Bank and SBI, respectively). Mr Balakrishnan said it almost amounts to criminal negligence by public servants because the resulting humongous losses are eventually dumped on the public exchequer. This, he said, is good enough reason to make the reports public. As Mr Bhushan says, powerful banks are bound to file a review petition. We, the people, are affected by the outcome and it is up to us to decide if we will watch in silence or support the fight to ensure that information that exposed the competence or otherwise and even corruption of those tasked with the job of protecting us is put in the public domain.

Rajendra Ganatra, a former banker, and R Balakrishnan, with vast research and fund management expertise, also pointed to superficial inspection, lack of follow-up and the lack of interest in setting things right in both the inspection reports analysed by them (Axis Bank and SBI, respectively). Mr Balakrishnan said it almost amounts to criminal negligence by public servants because the resulting humongous losses are eventually dumped on the public exchequer. This, he said, is good enough reason to make the reports public. As Mr Bhushan says, powerful banks are bound to file a review petition. We, the people, are affected by the outcome and it is up to us to decide if we will watch in silence or support the fight to ensure that information that exposed the competence or otherwise and even corruption of those tasked with the job of protecting us is put in the public domain.