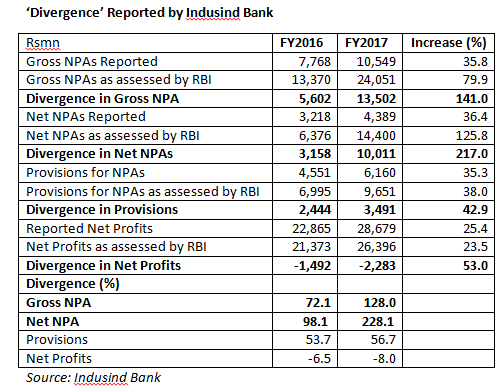

In a stunning blow to the credibility of Indusind Bank, its board of directors, Ramesh Sobti, chief executive officer and Russell I Parera, auditor and partner, Price Waterhouse, the bank reported that it had mis-reported its accounts for the year ended March 31, 2017. This was its second consecutive year of mis-reporting. The regulatory strategy of naming and shaming a bank by disclosing the difference between the regulator’s assessment and the bank’s view of its non-performing assets is clearly ineffective. It is shameful for any bank to mis-report accounts for a single year; for a bank to report two successive years of fudged accounts without any accountability for its CEO and the auditor speaks volumes on the quality of corporate governance. The regulator also does not seem to mind that banks are merrily reporting ‘divergence’ for successive years under the same key managerial individuals and auditors and they are able to retain their posts to continue with such a performance. Such malpractices renders meaningless any analysis of reported numbers. This is especially shocking for a bank which trades at 5.4x P/BV. It should also be shocking, but unfortunately is on expected lines, that analysts remain silent and are unwilling to aggressively hold management accountable, on fears of losing corporate access on a market favourite bank. For reporting two consecutive years of untrustworthy accounts, Indusind Bank joins the Hall of Shame and is in the company of Axis and Yes Bank.

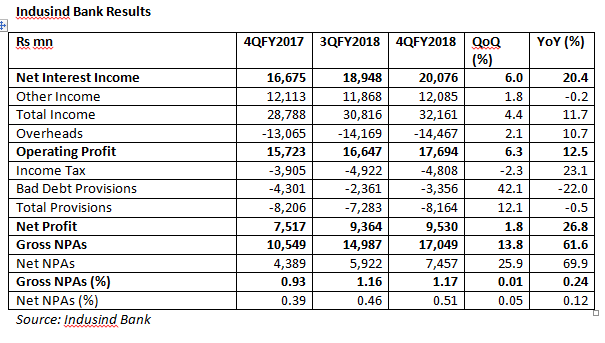

The main event of the bank’s 4QFY2018 results reported on April 18, 2018 was not that the bank was able to meet consensus estimates, but that it reported a second successive year of misreported accounts. More worryingly, the divergence, in absolute and percentage terms, was higher than in the previous year, indicating that the problems in regulatory compliance are only getting worse at the bank.

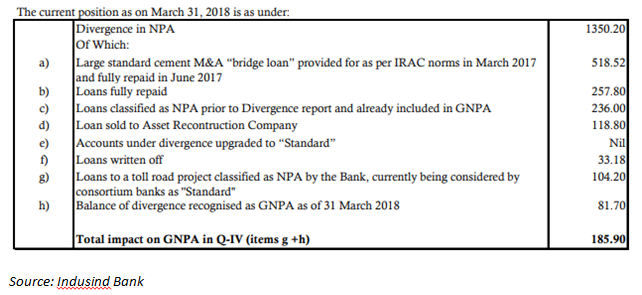

The Indusind Bank explanation for the divergence, attempting to highlight that the majority of it was addressed in FY2018, is irrelevant. The recoveries achieved, bad loans fully repaid, NPAs sold to asset reconstruction companies and other banks also classifying the account as ‘standard’ have no meaning, and no weightage must be subscribed to the bank’s defence. Investors must be aware of the factual audited position as on the year end. Subsequent events post the cut-off date are meaningless. Prudent accounting practice indicates the bank should have classified all these assets as NPAs. If and when recoveries or asset sales took place, the proceeds could have been written back. This is the normal practice and one cannot use this justification to explain the serious offense of under-reporting NPAs to boost the bank’s valuation.

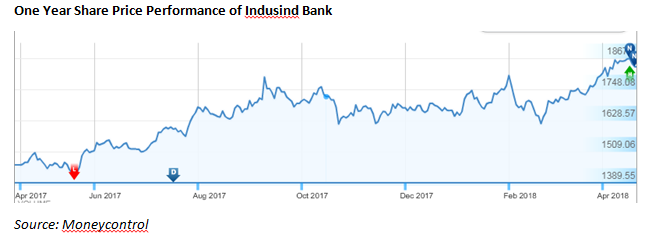

Indusind Bank’s conduct is shocking, as it is a market favourite bank, with considerable institutional and foreign ownership, and at 5.4x P/BV it is expensive by global and Indian standards. The secular growth in its share price and premium valuation leaves no room for such serious regulatory transgressions.

The numerous and experienced sell-side analysts who track the bank have so far remained silent when the bank disclosed in its FY2017 annual report that it had mis-reported FY2016 accounts. Their silence continued when the regulator fined the bank on December 13, 2017 for fudging the books. Even at the analysts’ meet to report its FY2018 results, the analysts chose to not grill the CEO and the management for this huge regulatory lapse which exposes the entire credibility of the accounts and the valuation in the stock market.

The surge in share price despite such setbacks indicates the market is also oblivious to spurious accounts, management culpability and docile analysts. The regulator’s conduct in all this also undermines financial credibility, and more importantly, financial stability, as the reporting of divergence by prominent, market favourite banks has become par for the course. When the regulator merely taps the wrists after the first offence, is it any surprise that the offender repeats the act?