Few people are looking at the connection between two developments.

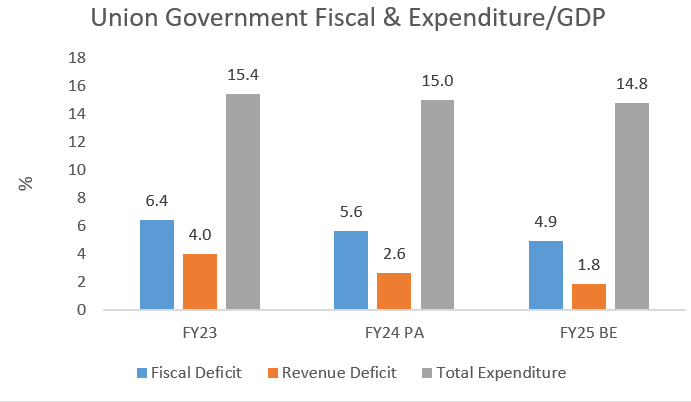

— First, India’s Finance Minister has been steadily bringing down the Central government’s fiscal deficit as a share of GDP. In fact, she has been so firm in this effort that total Central government spending/GDP has been falling in the process. Moreover, she has kept a lid on revenue expenditure and steeply hiked capital expenditure; thus an increasing share of Government borrowings is creating lasting assets.

This fiscal discipline has won praise even from her critics. Commentators have widely viewed the inclusion of India’s sovereign bonds in the JP Morgan Government Bond Index-Emerging Markets (GBI-EM) from June 28, 2024 as a recognition of India’s fiscal prudence and financial stability. Starting with a 1% weight, India’s weight in the JP Morgan index will gradually increase to 10% over the next 10 months.

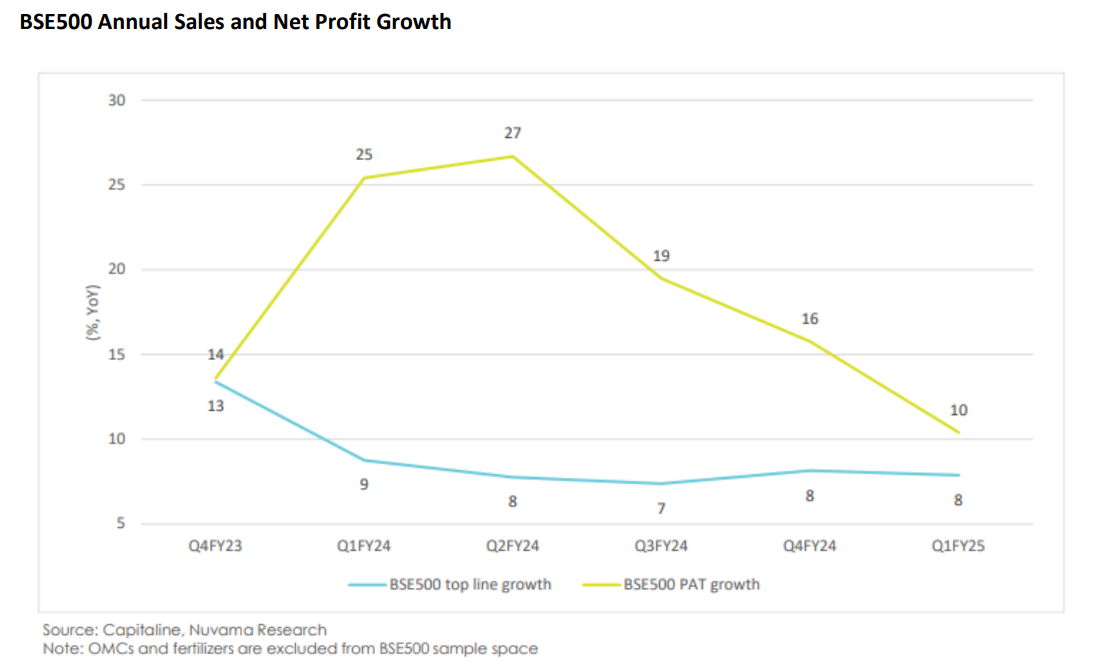

— Second, the latest data indicate that corporate sales have turned sluggish; and corporate profits, which were soaring last year, seem to be decelerating rapidly.

A broader sample of companies monitored by the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE) also bears out the finding of sluggishness in sales growth and fall in the growth rate of net profits. Business Standard data for Q1FY25 too exhibit a similar trend.

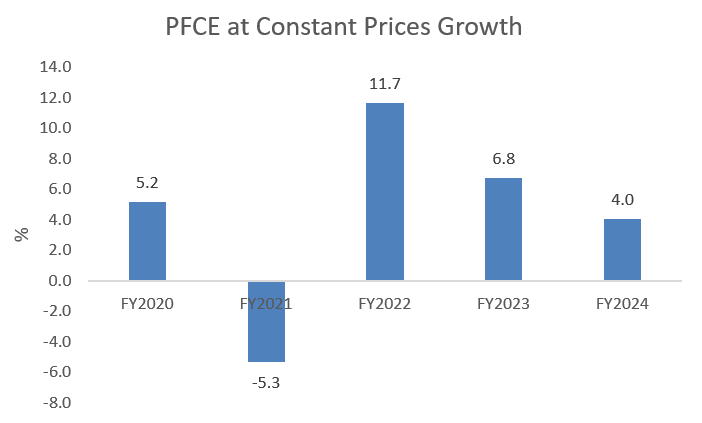

The single digit annual percentage growth in sales is a symptom of depressed aggregate demand in India. These indications of a slowdown in demand appear to be borne out by the macro data of private final consumption expenditure (PFCE), which accounts for around 55-60% of GDP.

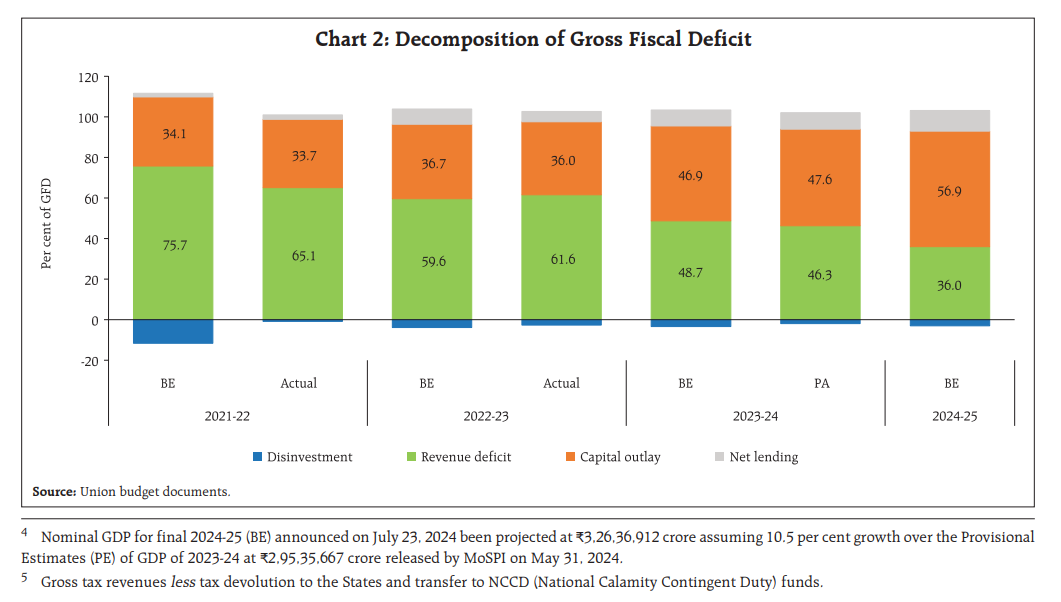

The Government’s stance, supported by many economists and commentators in the capital market, has been that it is increasing Government capital expenditure while reducing revenue expenditure. As a result of this policy, capital outlay has increased from 34.1% of the gross fiscal deficit in FY2022BE to 56.9% in FY2025BE. In contrast, the ratio of revenue deficit to gross fiscal deficit has drastically shrunk from 75.7% to 36% in the same period.

However, a note by PRS Legislative Research shows that, while budgetary outlays for capex have nearly doubled as a share of GDP between 2019-20 to 2024-25 (Budget Estimates), capex by public sector enterprises from their internal resources and borrowings has fallen by two-thirds as a share of GDP. As a result, the combined capex by the Central government and public enterprises has fallen from 4.7 per cent of GDP to 3.9 per cent of GDP. This is also reflected in the GDP data: investment in machinery and equipment by public non-financial corporations has suffered an outright fall between 2019-20 and 2022-23. Thus the public sector capex stimulus is illusory. At most the Central government budgetary outlays for capex have partly compensated for the shortfall in public enterprises’ capex. Demand is hit with a double whammy – lower Central government revenue expenditure, lower public sector capex.

The decline in total central government expenditure (as a percentage of GDP) is a contractionary policy. No doubt the Government claims that GDP data show decent growth overall, but the corporate sector has doubts about the claims of growth, since it sees a contradiction between the GDP data and private consumption on the ground.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating: private corporate investment in machinery & equipment and intellectual property products has refused to pick up, ignoring stern reprimands by the Finance Minister and the Chief Economic Adviser. Reserve Bank of India deputy governor Michael Patra noted on September 3 that the private corporate sector has drastically reduced its net borrowings from the rest of the economy from close to 9 per cent of GDP in 2007-08 to under 1 per cent more recently, “reflecting a combination of rising internal accruals and subdued capacity creation.”

If the corporate sector is right, and GDP growth is much lower than the official figures, a declining Central government expenditure/GDP ratio could already be worsening demand conditions.

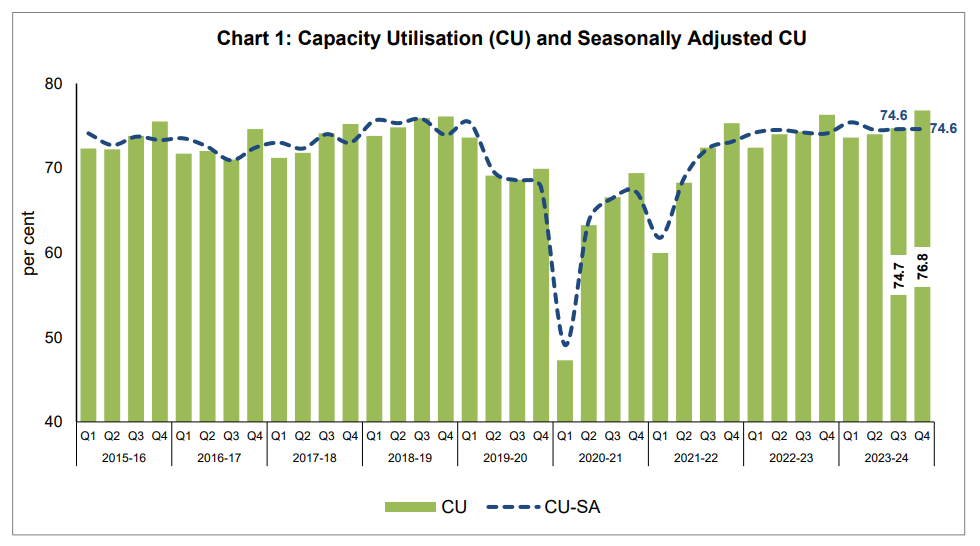

It is therefore no surprise that capacity utilisation is stuck in the mid 70% range and why the private corporate sector is reluctant to increase capacity.

There are broadly two theories of how to exit an investment slump like the present one. The first, which is widely propagated, is to step up reforms in such a way as to open up profit-making opportunities. This has been tried for some years by the Government, but has not yielded results.

The other way is to increase Government expenditure, and thereby stimulate demand. This would require a rise in the Government expenditure to GDP ratio. However, this is no longer easy, after India’s sovereign bonds have been included in the JP Morgan Government Bond Index-Emerging Markets. The decision to allow the inclusion in the JP Morgan index was justified on the basis that the surge of inflows would lead to the lowering of the interest rate of Government borrowing, and even corporate borrowing.

The problem is that foreign investors in bonds do not like an increase in Government borrowings, or even Government expenditures. They could vote with their feet if they see a change in fiscal policy. In a sense, the Government has effectively shackled itself with the JP Morgan index. It would be very difficult for the Government to announce a major fiscal expansion in the inaugural year of Indian government bonds being included in a prestigious emerging market government bond index.

The implication for the future is that, in the absence of an external stimulus in the form of a strong revival in global economic growth, and the absence of a domestic stimulus in the form of Government spending, the Indian economy may remain bogged down in an extended period of sluggish growth. The inclusion in the JP Morgan index may even have a further downside in a situation where there is a flight of capital from emerging markets, leading to a sharp spurt in domestic interest rates.

While the benefits of foreign participation in India’s government bonds are yet to be seen, the negative consequences are already visible in the form of a contractionary fiscal policy, which is further worsening the bleak demand scenario in the Indian economy.

This analyst would like to acknowledge inputs from the Research Unit for Political Economy

This article was also published in The Wire and can be read here

_________________________________________

DISCLOSURE

I, Hemindra Kishen Hazari, am a Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) registered independent research analyst (Regd. No. INH000000594), BSE Enlistment No. 5036. Please see SEBI disclosure here. Investment in securities market are subject to market risks. Read all the related documents before investing. Registration granted by SEBI and certification from NISM in no way guarantee performance of the intermediary or provide any assurance of returns to investors. The securities quoted are for illustration only and are not recommendary. Views expressed in this Insight accurately reflect my personal opinion about the referenced securities and issuers and/or other subject matter as appropriate. This Insight does not contain and is not based on any non-public, material information. To the best of my knowledge, the views expressed in this Insight comply with Indian law as well as applicable law in the country from which it is posted. I have not been commissioned to write this Insight or hold any specific opinion on the securities referenced therein. This Insight is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide financial, investment or other professional advice. It should not be construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation for any security.

All rights reserved. No portion of this article may be reproduced in any form without permission from the author. For permissions contact: