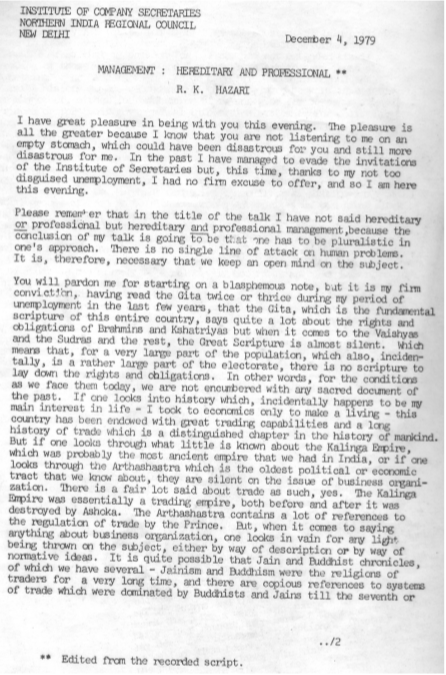

Edited transcript of a talk delivered to the Institute of Company Secretaries, Northern India Regional Council, New Delhi, December 4, 1979

I have great pleasure in being with you this evening. The pleasure is all the greater because I know that you are not listening to me on an empty stomach, which could have been disastrous for you and still more disastrous for me. In the past I have managed to evade the invitations of the Institute of Secretaries but, this time, thanks to my not too disguised unemployment, I had no firm excuse to offer, and so I am here this evening.

Please remember that in the title of the talk I have not said hereditary or professional but hereditary and professional management, because the conclusion of my talk is going to be that one has to be pluralistic in one’s approach. There is no single line of attack on human problems. It is, therefore, necessary that we keep an open mind on the subject.

You will pardon me for starting on a blasphemous note, but it is my firm conviction, having read the Gita twice or thrice during my period of unemployment in the last few years, that the Gita, which is the fundamental scripture of this entire country, says quite a lot about the rights and obligations of Brahmins and Kshatriyas but when it comes to the Vaishyas and the Sudras and the rest, the Great Scripture is almost silent. Which means that, for a very large part of the population, which also, incidentally, is a rather large part of the electorate, there is no scripture to lay down the rights and obligations. In other words, for the conditions as we face them today, we are not encumbered with any sacred document of the past. If one looks into history which, incidentally happens to be my main interest in life – I took to economics only to make a living – this country has been endowed with great trading capabilities and a long history of trade which is a distinguished chapter in the history of mankind. But if one looks through what little is known about the Kalinga Empire, which was probably the most ancient empire that we had in India, or if one looks through the Arthashastra which is the oldest political or economic tract that we know about, they are silent on the issue of business organization. There is a fair lot said about trade as such, yes. The Kalinga Empire was essentially a trading empire, both before and after it was destroyed by Ashoka. The Arthashastra contains a lot of references to the regulation of trade by the Prince. But, when it comes to saying anything about business organization, one looks in vain for any light being thrown on the subject, either by way of description or by way of normative ideas. It is quite possible that Jain and Buddhist chronicles, of which we have several – Jainism and Buddhism were the religions of traders for a very long time, and there are copious references to systems of trade which were dominated by Buddhists and Jains till the seventh or eighth century A.D (quite independent of the substantial Jain participation in trade even now), contain something on business organization. I must confess that my passion for history has not extended itself into reading of these chronicles and I would not claim to have found either something or nothing in them. We do have references in Moghul and Maratha history to the dependence of the State upon bankers in one form or the other, either for collection of revenues or for borrowings by the Princes or for their governmental information system or for collections economic information generally. We also have information about the Nagar Sheths of Ahmedabad, which is a fairly well documented history, from which one can get some information about how business was organized in early stages of the development of Ahmedabad as a metropolis. We also know something about the trading organization and the behaviour of the agents of the East India Company. One of the great features of the East India Company or the Merchant Companies generally, was that they permitted small groups of traders to float enormous enterprises on the joint stock principle, to share their profits such as they were, small or enormous. They allowed their agents or factors as they were called (and that is how their establishment came to be known as factories) to trade on their own, and you thus have the laying of the foundations of a new business class which earned its money from the operation of such factories. We also have rare study of the history of a relatively modern business organization in the traditional framework, the study of the House of Surajmal Nagarmal which was the first Marwari business house in Calcutta and from which a number of the present business houses in Calcutta have arisen. The house itself, as you know very well, is not one of the more prominent houses as of now. From Western sources we do know – and this has some universal application and validity because you find references to that not only in odd chronicles in India, but also in places a; far away as Mexico, Egypt and Greece, maybe something even in Phoenician times – that there were guilds of merchants and craftsmen and entry into these was very closely regulated, whether one entered by means of hereditary privilege or one was apprenticed into it from an early age. Quite apart from any Government regulations that there might have been, there was very close regulation of entry, behaviour and dress by the guilds of merchants as well as of craftsmen. I am mentioning these, because anything that you have as of now is the result of historical evolution. Nothing comes up suddenly. If one were to see how things have evolved over a period of time, one should be able to understand what has happened in the past. For better or for worse, we are heirs to a great tradition of the past. However, the study of business organization in a regular and systematic manner has not been as exciting as the organization of government or the description or analysis of military campaigns. Therefore, we know very little about the history of business organization anywhere in the world. These studies are of relatively recent origin.

What we call culture or civilization is not something that exists on paper nor does it consist only of books or music or painting or sculpture. It is the ultimate result of the creation of an economic surplus which arises intrinsically from agriculture, from trade, from craftsmanship and from an environment of a liberal government which allows people to function without too much regulation or which creates the environment in which the economic surplus can, first of all, be created arid, then, be utilised. Much of what we call civilization or culture is really a means of utilizing this surplus for the means of living and for enjoying the leisure that goes with a style of living in which there is sufficient surplus to make possible activities other thin bare subsistence. It is in the light of these overall factors that one has to see why there is so much stress these days on management. How is it that we did not have much talk about management till, let us say, a hundred years back? It is only since roughly the last quarter of the nineteenth century that we have emphasis upon management as an important factor, upon the evolution of new managerial classes at various points. While there is a long history of trading families and of the employees of those trading families or banking families, if you like, the large class with which you identify yourself, the new managerial class of which you are an important component, is a relatively recent phenomenon. The rise of the new managerial classes is, first of all, connected with the professionalisation of the army and the civil service. Till a hundred years back, there was no such thing as a professional army, except for a few mercenary groups here and there who offered their services for a consideration to anybody who paid them, and the civil service was largely an organization of certain families which inherited their positions or which were rewarded for certain military obligations. The only relatively organized professions since the dawn of recorded history have been those of the priesthood or of the military class but both these had objective other than the creation of an economic surplus or its management. The military and the priesthood do certainly take care of the utilization of the surplus.

The second reason for the rise of the managerial classes is non-linear change over the last hundred years or so in the scale of operations of economic entities in which the turnover is very large and the operations cover a very wide area. Even in ancient days, many trading operations did cover large geographical areas but these essentially connected a few ports, a few ancient trading routes. They did not penetrate much into the hinterland. This great boosting of the scale of management, and the application of technology which has brought about a tremendous change of scale, has led to the creation of new classes, the creation of new forms of organization to take care of the business activities of large firms. If you have a bullock-cart economy, you have one kind of business organization and you have one kind of business class. It is not the bullock-cart drivers who created the technology which made the railways possible. You put any number of bullock-carts together, you do not get a railway train. The rise of the railways, the rise of other forms of transportation, coming as a result of the application of technology and the people required to work that technology, have created the new classes of which you are one of the essential components. There has also been over the years, a growth of large companies, after these merchant companies from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, of which the East India Company was one, which has now blossomed forth into what are called multinationals, or what are the large public enterprises of today. They are the ultimate historical result of what the merchant companies achieved long ago. Alongside these, there has been a change in the social structure, with much greater horizontal mobility in the sense that people move from one geographical area to another, and much greater vertical mobility in the sense that people move from one class to another or from one status level to another. As compared with any other period in the history of mankind, the elite class in human society all over the world today is much more open than it ever was. While many of us would like it to be still more open, the fact still remains that it is more open than it ever was. This openness and the greater vested interest in the openness arises from the fact that, unlike past times, the application of the new technology leads both to mass production and mass consumption. The elite to which we belong has a vested interest in the promotion of mass production and mass consumption, rather than in self-sufficiency because, in a state of self-sufficiency, there are no remunerative prospects of employment for you and me. When there is a conflict between the elite and the older elite which prefers to think in terms of traditional agriculture or traditional industry or a traditional social organization, you have to remember that it is not merely a confrontation between old and new, it is also a confrontation between different vested interests.

In present day society, as in history, there is no such thing as different stages of growth. It is not as if one move wholly from a primitive social order or social organization, to advanced social organisation or social order. Every society is an amalgam, a broad spectrum of the coexistence of many different forms of technology, many different forms of religion, many different forms of organization, many different forms of behaviour. Some people do believe that one moves from stage A to stage B to C towards Z. There is no such thing in historical evolution. You look around yourself in this great capital of a great country. You find, simultaneously, great modern which are being multiplied all the time, and ancient monuments going back some thousand years, a heterogeneous time span in between. You have people who live a life which is not substantially different from the life of those in New York or London or Paris; you also have people whose standard of living, whose ways of behaviour are not substantially different from those in a remote village. You have people who believe in the utmost rationalism, at least outwardly, you also have people who believe in the most primitive forms of worship, primitive as we understand them to be or we describe them to be, with all kinds of behaviour, practices, rituals in between. What is more, the same people who might be very rational and scientific during working hours are terribly religious or superstitious or ritualistic outside working hours, say, in their family matters. There are people who might be very “progressive” in their speeches before the public; they might be terribly “reactionary” in their behaviour within their social organization. People might have one kind of behaviour when it involves their sons, they have another kind of behaviour when it involves their daughters. These things do co-exist. Therefore, there is nothing wrong, there is nothing irrational, there is nothing historical, I would say, in contemplating kinds of organizations or kinds of organisational practices or systems which, on the surface, might appear to be inconsistent with each other but which, nevertheless, do co-exist, which can co-exist or which can be made to co-exist

We have to realize that if, you have, for instance, large or giant enterprises which have promoted the growth of what is now called professional management, it is a result of a variety of factors. There has been an increase in the scale of operations of business organizations; even if you deflate for the increase in prices, you still have a very substantial increase in the scale of operations of many economic entities. They require a variety of skills all of which were not required before; even if you deflate these skills for the “superfluous” elements that have to be practised in order to deal with rituals, whether private or governmental, many of which might be not very productive socially, the variety of skills that is required for running a large modern business organization is such that it entails the growth of people who cannot be supplied from the owning family itself. I remember somebody telling me many years ago in Bombay, that the Tatas employ only Parsees – to which my reply was that, statistically, that is not possible. The number of people that the Tatas employ, have to employ, the kinds of skills that they require for their operations, the places in widen they are required, all are such that these numbers and variety cannot be net from the scarce Parsee community that exists in the world. Therefore, even if they wanted to employ only Parsees, they would have to employ other people. All that they could do, when they wished to employ Parsees was to keep certain key positions in the hands of the Parsees. I am taking the smallest trading community in India as an illustration to point out that even if you had a policy based upon a family or kinship organization to control large business operations as of now, it is statistically and qualitatively not possible, to meet all your requirements from one small group. It has been said, that since independence this country has been under Kashmiri or semi-Kashmiri rule. The number of Kashmiris available for the purpose has always been strictly limited and, therefore even if the cream of the cream was taken away in favour of Kashmiris, there was enough left over for the others too. What this indicates is that you can delegate authority to other people on the basis of a confidence system which you might consider is natural or inborn. If somebody misbehaves, you do not depend upon the methods of enquiry laid down in Government manuals, you do not keep on asking for banking references, you don’t keep on checking on credentials . The traditional system of confidence and control is that you hold hostages from the family or through control over the family in the so-called native place or because you employ sufficient numbers of the kinship group, to punish some others, when a particular member misbehaves. In any case, you know them so well, that you knew their plusses and minuses. However, even this works only up to a point. You take the Birla system of financial control, which probably is one of the finest systems of control anywhere in the world. It is true that a few trusted men in the Birla croup belong more or less to the same kinship organization. The contribution or the Purta as it is called is worked out on a daily, weekly, monthly and annual basis. And so long as that is being met, not many mere questions are asked. It is true that this is supplemented by various other kinds of controls, positive and negative. But Birlas don’t have to use police methods against their trusted folk. They don’t have to use the formal methods such as are known in public enterprises or in multi-national companies but there is a formal Purta system which has to be observed. Most of the control mechanism might be informal but there is a formal element. Even while we are contemplating so-called modem methods of management or the Harvard style of management control, let us not forget that we also have a nucleus of a system of financial control or managerial delegation which has stood not only the test of time, it is standing the current test of operations and performance. What I am trying to point out is that, in respect of the larger enterprises, where one does need what is described as professional management, no particular purpose is served by identifying that professionalism with what are described as Western or Harvard concepts only. There are native traditional systems of management which do need to be adapted, which do need to be adjusted, which, I hope, in course of time would break away from the ties of kinship and blood and place of origin and So forth but which have stood the test of time and which are standing the test of present performance and opportunities, and which we need not throw away.

As we see the growth of these professional classes as a result of the application of technology and the increase in the scale of operations, please remember that, at the same time, the development opportunities that have been created in our society by the economic changes during the last thirty years, more particularly during the last ten or fifteen years, are also creating new opportunities for the rise of family enterprises, the expansion of a petit bourgeois which is being supported with the extension and expansion of banking and the green revolution with all the opportunities for development of trade and transport that it creates in the interior. Alongside the growth of people like you and me, therefore, there is taking place the growth of farmers or families as entrepreneurs, growth of new traders in the countryside, the growth of small traders in the towns and in the cities who function without the kind of professionalism that comes from a formal education or from a formal training. If one is taking a total view of Indian society as it is, and as it is going to be and if one keeps in mind that our population is 650 million and it will keep on growing for a long time to come, and that we, the so-called formal professional classes are a relatively small element in the aggregate of society, then, the bulk of the economic units that we have in this country are essentially family units, they are essentially family oriented and for the bulk of the numbers involved, they do not directly need professional training and professional organization. They require various other inputs which do involve professionalism. They are dependent upon transportation, they are dependent upon a new technology which has to be constantly evolved and which, therefore, requires a professional class. They are part of a social organization in which whether you have politicians of one sort or the ether or, technicians of one sort or the other or, civil servants of one sort or the other, these are all inter-dependent. In many forums professional management is being held out as a panacea. I don’t see how it is a panacea. Because, for the bulk of the economic units that we have in the country, family ownership and family management will remain and will continue to flourish and will probably expand as we move from a subsistence or near-subsistence economy on to a much greater surplus economy than we have already witnessed. At the same time we do need much more professionalism. I am all for it. I have a vested interest in it. I make my living out of it. My prospects depend upon it. But, let us not lose sight of the totality and of the implications of that totality. We need not run down family ownership or family management. Nobody seriously in his senses has suggested complete- nationalization of land or of all means of production. What we need is to understand that there is a broad spectrum, that the strength of this country has always lain in its diversity, and we have always flourished when we have not only tolerated this diversity and variety but have actively promoted and supported it whether in matter of religion or in matters of social organization or in matters of technology or in matters of social organization. Therefore, when we think about management, let us think of the tasks that have to be performed, the objectives that are set before us, rather than of dividing society into castes and spying who is superior to whom or of saying that a now caste will perform new functions. Let us not import the old caste system into new functions. The new functions are such that they require much greater mobility not only of persons, but also of thinking, greater mobility and flexibility of institutions and organizations. For that it is necessary, first, that we accept that while there is need for centralized direction, in the sense of giving a direction to society and to the economy, at the same time, we need decentralized initiative in the sense that people should be able to function on their own and not grow over-dependent upon outsiders. Why do we depend upon Government for everything? Why do we depend upon somebody else to do everything? Individuals and groups should be able to do many things on their own. If we believe in centralized control as distinct from centralized direction, we also have too much centralized responsibility and, therefore, we will have no initiative left among the units concerned. It is also necessary to accept that innovation has a value in itself and that we should have minds and institutions that accept innovations. If every move requires the prior approval of somebody, whether it is a Brahmin or a Kshatriya as it was of old or, whether it is a Government official or a politician, as of now, then, I am afraid we are acting in a style that would cramp initiative, which would make it extremely difficult to maintain the diversity that I talked about earlier. Third, for better or for worse, we do have in our existing social organisation a system of confidence based on kinship. Whether we like it or not it is there. Howsoever much we might deny it, the fact of the matter is that it is there, it is going to be there for quite sometime to come. Almost everybody likes to say in public, I don’t believe in the caste system. Nevertheless, when the son or the daughter has to be married, the caste system is very much there. Where there are any social functions, the caste system is very much there. When there is any so-called political thinking or action, the caste system is very much there. Now, I am not sufficiently revolutionary or missionary in my attitudes to say that this must be totally changed tomorrow morning. I am sufficiently realistic, I hope, to know that this can’t be done tomorrow morning. It won’t be done for many mornings. If that is so, let us use such organizations and such systems as we have consciously, till we can find better ways of doing things on a larger scale. If kinship is the basis on which our organisations work, let us expand the concept of kinship. Let us make it more broad-based. If this is the system of control that we have, till such times as we can have a better, more effective and, I hope, more economical system ultimately, let us use the kind of control systems that we have.

It is in this light that one should take a view about family or hereditary, and professional management. There is no doubt that when you have hereditary management, there is a degeneration at least after the second or third generation but, mind you, degeneration is not ruled out in professional management, either; there are cases on record even in Indian companies of professional management also degenerating over a period of time. But, generally, it would be true to say that heredity does tend to destroy itself over a period of time. What we need, therefore, is more and more professionalization, but we also need more families to replace if you like the older families. You can’t get away from family ownership of management so long as that economic and social system is recognized and is being promoted in any case as part of economic and social policies. If that is so, let us recognize that since family units are there, and will remain there, that there would be a hereditary principle. What we have to do is to keep the hereditary principle on a family basis such that one does not think of the heredity of the same family but of more and more families coming into the picture so that one gets a much broader base rather than one restricted to a few families alone. I do not know how people came to the conclusion, when my reports were put out, that I was against business groups or against business as such. If you would kindly read the conclusions chapter of my book, you would find that my answer to the problem of concentration was to increase the number of business groups, not destroy or break them up. I would have a similar principle, not only for hereditary or family management, but even for professional management. If you leave professional management also in a secure compartment without having to face competition from new groups always coming in or threatening to come in. you might get same adverse results. I think I have already spoken too long. I thank you for listening to me patiently and for enduring this tour through history.