India’s private sector banks were held up for years as the standard of efficency and corporate governance to which public sector banks should aspire. But now it emerges that private bank after private bank has in fact been harbouring bad debts, fudged accounts, corrupt deals, gross mismanagement, overly paid CEOs and delinquent boards.

These revelations should not be treated as an unrelated series of incidents. It is time to question the theoretical underpinnings of the Reserve Bank of India’s hitherto ‘hands off’ style of regulating these banks. And time for us to realise that what goes on inside the banks concerns not only the banks, but the economy as a whole.

According to the currently reigning economic doctrine, self-interest ensures efficient outcomes. We are told that the private sector, acting in its rational self-interest, chooses wisely, but the public sector tends to be guided by political pressures and corruption. Hence the alleged “phone banking” of Government-owned banks: that is, public sector bankers were said to have taken credit decisions based on phone calls from bureaucrats and politicians for favoured industrialists.

Correspondingly, the reigning doctrine presumes that, when banks are listed on the capital market, and foreign and institutional investors buy sizeable stakes in them, the boards and managements of these banks would exercise due diligence, ensure transparency, and protect shareholders’ interests. Under the eagle eye of private investors, corporate governance standards in these banks would rise.

Private sector governance on display

Indeed, a few years ago, the Committee to Review Governance of Boards of Banks in India (the Nayak Committee) raised the alarm over the “fragile” state of bad debt-ridden public sector banks (PSBs). In its Report of May 2014, it contrasted the weak and disempowered state of PSB boards with the relatively active and engaged nature of the boards of private sector banks. It thus recommended that the Government stake in all PSBs be brought below 50 per cent. Further, it called for the creation of a category of Authorised Bank Investors, who could hold a stake of 20 per cent in the bank without regulatory approvals, or 15 per cent if they also had a seat on the bank board.

This notion of the superior quality of private sector governance has not fared too well in the last few months. The newspaper-reading public has witnessed the spectacle of Chanda Kochhar’s brazen conflict of interest at ICICI Bank, Shikha Sharma’s mismanagement at Axis Bank, the lack of accounting integrity at both Axis Bank and at Rana Kapoor’s Yes Bank, and the complete collapse of corporate governance by Ravi Parthasarthy’s team at Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services Ltd (IL&FS). In all these cases, the boards of the banks, decorated with ‘independent’ directors, played the role of either mute spectators or cheerleaders for the delinquent managements.

What has not been remarked on is that this has happened despite significant foreign institutional holding in these listed entities, and despite the presence of prestigious foreign and domestic institutional investors’ nominee directors on the board of the IL&FS (which is unlisted). Where scattered, less-informed shareholders might not be able to influence the management of a firm, these were cases of concentrated, well-informed, and at times board-represented investors. According to the reigning dogma, the significant foreign and domestic institutional ownership in these entities should have resulted in better corporate governance standards in them, failing which they would have been disciplined by the market. But in reality, no such thing took place.

Cooking the books

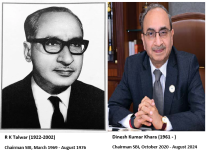

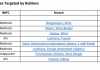

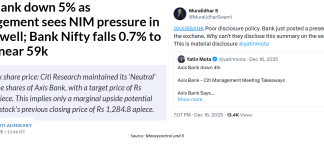

In the case of Axis Bank, on July 27, 2017, nearly 10 months before Shikha Sharma’s term was coming to an end, the board of directors announced a fourth three-year term for her, commencing from June 1, 2018. This was after the bank had reported a 56 per cent fall in net profits for the year ended March 31, 2017, and simultaneously reported that it fudged its accounts for the year ended March 31, 2016 by overstating its net profits and under-reporting its non-performing loans. Shareholders received a further jolt a few months later on October 17, 2017, when the bank reported that the Reserve Bank of India had found that Axis had misreported its financials for March 31, 2017 as well.

In the capital market, cooking the books is meant to be an extremely serious offence, as the market valuation of companies is said to be based on the financial accounts, as is senior management’s compensation. Therefore, following any mis-statement of accounts, the board should have held the chief executive officer responsible and removed the individual, and if the board failed to do it, institutional shareholders should have exerted pressure on the board to adopt this stringent punishment. The shareholding pattern of Axis Bank on July 21, 2017 reveals foreign holding of 52.55 per cent and Indian mutual fund holding of 7.54 per cent. Despite information in the public domain that Axis Bank had fudged results for the year ended March 31, 2016, not only did the board prematurely announce a fourth three-year term for Shikha Sharma, but the majority of shareholders did not seem to object to such an individual being appointed by the board for a fourth term.

A similar story unfolded in Yes Bank, where the bank reported two successive years of fudged accounts for the years ended March 31, 2016 and 2017. The bank’s shareholding pattern as on March 31, 2018 shows foreign portfolio investors’ holding at 42.6 per cent, Indian mutual funds at 10.3 per cent, and insurance companies (excluding Life Insurance Corporation) at 14.2 per cent. In Yes Bank’s case, not only did the board decide to re-appoint the promoter-CEO Rana Kapoor for another 3-year term commencing September 1, 2018, but the shareholders at the annual general meeting held on June 12, 2018 with an “overwhelming majority” approved the decision. The majority shareholders, consisting of foreign and private sector institutional investors who manage other people’s money, were content to appoint a serial mis-reporter for another 3-year term.

Interestingly, the Nayak Committee did mention the incentives for ‘evergreening’ (i.e., covering up bad debt by extending more loans to the borrower to avoid default) in private banks, and it called for some measure of RBI random inspection to check this. But this point of the Committee’s report, however inadequate, has been selectively buried, and only its pro-‘liberalisation’ recommendations have been publicised.

Promoter rewards himself at the cost of shareholders

The case of Kotak Mahindra Bank (KMB) is also interesting. In its February 28, 2005 guideline, the RBI emphasised diversified ownership, and laid down that a single entity or group of related entities could hold a maximum of 10 per cent in a bank; higher levels required RBI approval.

Thereafter, as per the RBI’s revised guidelines for licensing of new private banks issued on February 22, 2013, it stated that the promoter should have a maximum shareholding of 15 per cent “within 12 years from the date of commencement of business of the bank.” For KMB, the RBI’s latest guideline meant that by February, 2015, the promoters’ shareholding should have been 15 per cent. However, for Uday Kotak, the RBI gave extraordinary ‘regulatory forbearance’ (i.e. leniency) to reduce the promoter holding in KMB to 20 per cent by December 31, 2018 and 15 per cent by March 31, 2020. In all, that amounts to an extension of five years. As on June 30, 2018 the promoter’s stake in KMB was 30 per cent while foreign portfolio investors was 39.93 per centand Indian mutual funds was 6.85 per cent.

Thus as KMB’s share price has consistently risen (from Rs 657 as on March 31, 2015 to Rs 1,342 as on June 30, 2018), the regulator’s forbearance has resulted in a huge notional loss to the non-promoter shareholders of KMB, and corresponding undue gain to the promoters. The undue gain is estimated by this writer to be US$ 2.3 bn (Rs 156 bn, or Rs 15,600 crore). This analysis factors the gains (capital + dividends) accruing to the promoters by not selling their excessive shareholding (i.e. beyond 15 per cent) on March 31, 2015. The foreign portfolio and Indian mutual funds did not protest that this huge gain could have accrued to them instead of the promoter if the RBI had insisted on the promoter shareholding being reduced to 15 per cent by March 31, 2015. Worse, in an audacious move, the board of KMB issued ‘preference capital’, which is akin to debt and has no ownership and voting rights, and tried to include it in ‘paid-up capital’. They thereby claimed that, following this issue, the promoter stake came to 19.7 per cent of capital, conforming to the RBI norm. The RBI rightly rejected this classification.

Passive ‘sophisticated’ investors

The combined market capitalisation of KMB, Axis and Yes Bank, at Rs 417,727 crores, is very significant as compared with SBI’s Rs 236,502 crores. In all three cases of private banks, foreign investors and Indian mutual funds own collectively either the majority of shares, or more than the promoter, but in none of the cases did these shareholders exert their influence on the board of directors to adopt measures which would benefit the non-promoter shareholders. In all the three banks, the board of directors, completely failed to protect the non-promoter shareholders’ interests. If it had not been for the banking regulator which rejected the decisions taken by all three bank board of directors, the non-promoter shareholders would have lost out.

In IL&FS, an unlisted company focusing on developing infrastructure as a project owner and as a financer, the long reign of mismanagement of a single CEO finally resulted in huge losses for the consolidated entity in the year ended March 31, 2018, and the company began defaulting on its financial obligations by early September 2018. What is interesting to note that it had pre-eminent shareholders who had their nominee directors on the board, such as LIC, Orix Corporation, Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, State Bank of India and HDFC. Yet during this entire duration, senior management remuneration kept increasing, even while consolidated losses were rising. Despite having nominee directors on the board, these prominent shareholders presided over a company where the important risk management committee only met once in the last four years, and apparently were unconcerned at how the business strategy was unravelling.

The purpose of diversified ownership, listing on the capital markets and the presence of nominee and independent directors is to ensure that the promoter and the executive are kept in check, that they do not exceed their authority and that independent directors protect non-promoter shareholder interests. But in all these celebrated companies, not only did the independent directors fail in their responsibilities, but the foreign portfolio investors, Indian mutual funds and private sector insurance companies also failed to influence the management of these institutions.

Much is made about the lack of corporate governance in the PSBs and public sector financial institutions, but the recent shenanigans in the private sector banks and financial institutions reveal that mismanagement is not only rife in the board of directors, but that it is tolerated by the institutional investors, whose presence, it was claimed, would improve corporate governance and performance. What then of the claimed benefits of lowering the Government stake in public sector banks?

Myths take a beating

The abject failure of major foreign and domestic investors to monitor the banks in which they invested remains something of a mystery. Why would profit-oriented investors, endowed with armies of analysts and with the power to demand detailed answers from managements, remain passive spectators as the banks went astray? One possible explanation is that, as long as the going remained good, these investors behaved like any ordinary retail investor. Like consumers who stick with a well-known brand when buying toothpaste or detergent, it seems these supposedly sophisticated investors did not bother to open the lid and look inside the box, but stuck to the big ‘brands’ – the management personnel celebrated in the media.[2] That is, they preferred to remain passive rentiers, with no positive role to play. So much for the mystique of private investment.

The ‘light touch’ regulation which the RBI has been following in recent years, particularly for private banks, is based on the notion of a perfectly-informed, rational, self-regulating capitalism, and within that a self-regulating financial sector. That notion should have been debunked once and for all by the experience of the global financial crisis which began in 2008; at any rate, the current mess in India’s private banks has certainly refreshed that lesson.

It is important to realise, moreover, that the fate of the banks cannot be left to their boards. The ‘stakeholders’ in banks are not limited to the management and shareholders, or even their depositors. Banks by their nature are highly ‘leveraged’ institutions – their borrowings are very high in relation to their capital, and hence any sizeable deterioration of a bank’s assets threatens the bank itself. At the same time, banks are critical to the functioning of the whole of a market economy – no sector of the economy can function without finance, and so when there is a banking crisis, the entire ‘real economy’ too goes into crisis. Even when there is not a full-blown banking crisis, a slump in bank lending, as at present, slows the entire economy.

Hence the ‘stakeholders’ of the banking system are all participants in the economy, that is, the entire citizenry. Any laxity with banking regulation can bring the economy to its knees. This calls for highly active, intrusive, and continuous regulation by the regulatory authorities, in particular the Reserve Bank of India. The sorry story of India’s stellar private banks tells us what happens when, under the spell of some dubious theory, the RBI fails to do that job.

[1]Research analyst (http://hemindrahazari.com/index.html). Thanks to RUPE for comments and conversations.

[2]Indeed, when the board of Yes Bank put in a fresh plea to the RBI for extending the tenure of Rana Kapoor, the bank’s share prices immediately rallied, although it has since declined.