In an unprecedented act, Kotak Mahindra Bank (KMB) on December 10, 2018 filed a writ petition in the Bombay high court against the Reserve Bank of India. The writ prayed for permission to include its preference capital (a debt instrument) issue in paid-up capital, thereby lowering the stake of the promoters (essentially, that of Uday Kotak) in the bank to 19.7%.

As per the regulator’s directive, the promoter stake in the bank had to be brought down to 20% by December 31, 2018.

Uday Kotak and Kotak Mahindra Bank had been given special regulatory relaxation by the RBI, as the lengthy timeframe provided to the bank to reduce the promoter stake was not given to all other individual promoter-managed banks.

And the bank, in its wisdom, decided to finally return the favour by not only filing a writ petition against the regulator, but also alleging that as per Section 12 and 12b of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949, (BRA) the RBI is not empowered to “issue directions to banks to reduce their promoter shareholding or otherwise contemplate reduction of shareholding of any person in a bank.”

Table 1: Shareholding of Select Large Subsidiaries of KMB as on March 31, 2018

| % | Kotak Prime | Kotak Securities | KM Capital | KM Life Insurance | KM Asset Mgt | KM Investments | KM Inc | KM Gen Insurance |

| Sector | Auto Finance | Brokerage | Inv Bank | Life Insurance | Mutual Fund | Gen Insurance | ||

| Kotak Mahindra Bank | 51.00 | 74.99 | 100.00 | 77.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 51.00 | 100.00 |

| Kotak Securities | 49.00 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Kotak Mahindra Capital | – | 25.00 | 12.40 | – | – | 48.99 | – | |

| K M Prime | – | – | – | 10.58 | – | – | – | – |

Uday Kotak’s decision to not reduce his stake in the bank to 20% by December 2018, and finally to 15% by March 31, 2020, may be on account of the corporate structure of the Kotak Mahindra group.

KMB sits at the pinnacle of the structure, and is also the holding company for the entire group. KMB is the majority shareholder of all the major companies in the group (Kotak Prime, Kotak Securities, Kotak Capital, Kotak Life Insurance and Kotak Asset Management), and in all the subsidiaries the group owns 100% of the shareholding. The structure was devised so as to capture the valuation of all the group companies into KMB, which was the sole listed entity in the group.

It served the purpose, as the valuation of KMB soared, benefiting Uday Kotak, the promoter-CEO.

Such a structure is often frowned upon by banking regulators, as the risk of the entire group ultimately falls on the unsecured bank depositors in the parent bank. If Uday Kotak’s stake in the bank comes to 20% by the end of 2018 and 15% by March 2020, his ownership stake and, critically, his influence in the entire Kotak group, will decline. Alternatively, if nobody challenges him, he can control the entire group by holding a mere 15%-20% of the equity of the bank.

Hence, for Uday Kotak, the lowering of his holding in the bank has crucial implications for his ownership and control of the entire Kotak group of companies. It is pertinent to note that in the correspondence with the regulator to not reduce his stake, this argument is not mentioned.

The trail of correspondence exchanges between the regulator and KMB reveals the repeated relaxations provided by the RBI to the bank. In the exchanges made public, KMB reminds the regulator that when it was given it a banking license, the minimum promoter shareholding was 49%; hence, it argues, it is unfair for the regulator to change its stance.

When Kotak finally realised that the RBI was unrelenting in giving him any further extension on December 31, 2018 deadline, the bank issued preference capital on technical grounds to lower promoter stake in paid-up capital, without first informing the regulator as required. And when the RBI rejected it, and issued the bank a show cause notice, KMB filed a writ petition in the Bombay high court requesting a stay on the RBI’s action.

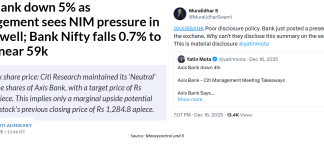

In the exchange of correspondence between the regulator and KMB, transparency to stakeholders was a major casualty. When the executive director, RBI, rejected the bank’s contention of a dilution of the promoter holding post the issue of the preference capital, the bank only disclosed part of a sentence of the RBI letter. The RBI’s complete letter dated August 13, 2018 had strong words of regulatory disapproval for the bank’s conduct, which the bank conveniently and deliberately ignored while recounting the exchanges.

In fact, the RBI had emphasised two other sentences in italics which are of material interest to stakeholders, namely,

“3. …You had further assured that the bank would keep us apprised of further developments in this regard.

6…We have taken serious exception to this, which amounts to wilful non-disclosure sought by the Reserve Bank.”

Wilful non-disclosure of information sought by the banking regulator is a serious violation, yet KMB withheld this material information from the exchanges. This information would have indicated that the bank was deliberately antagonising the regulator, and that regulatory stricture was a distinct possibility.

It was therefore no surprise that the regulator followed up the letter with a Show Cause Notice (SCN) on October 29, 2018 for non-disclosure to the regulator, under Section 35A, 46 and 47A of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949.

Although RBI’s disclosure requirements mandate only the penalty to be disclosed by the bank, and not show cause notices, the severity of the SCN to KMB should have been disclosed to the exchanges in the interests of transparency and corporate governance.

Rohit Rao, communications chief of KMB, defends the bank for not disclosing the critical RBI correspondence with the bank and on the issue of penalties states,

“We refer to your queries. You have referred to Section 47A of the the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. Section 47A is for imposition of penalty. It is not for imposition of imprisonment or fine. There are no allegations with criminal consequences in the Show Cause Notice. The bank has complied with its relevant obligations under law including SEBI LODR.”

But his boss, Uday Kotak, in his avatar as the chairman of the SEBI-appointed committee on corporate governance, eloquently argues in the report,

“While companies, in general, comply with the regulatory minimum, the Committee encourages boards and managements to view disclosure and transparency as a means to build trust with stakeholders and to proactively disclose material information that may impact decision-making variables.”

It is very apparent that Uday Kotak as chairman of a committee on corporate governance argues for greater than the minimum transparency but Uday Kotak as promoter-CEO of KMB practices the bare minimum.

Strangely, for a bank with a market cap of Rs 2,36,386 crore which adopts the reckless action of filing a strongly worded writ petition against the banking regulator, the media appears uninterested to disclose the contents of the writ.

To date, in the media, only BloombergQuint and The Wire disclosed the specifics. The writ contained correspondence which is rarely seen by the public, and the business media should have actively competed to disclose and analyse its contents. But in doing so, the media would have had to criticise the conduct of one their much-sought-after CEOs.

CNBCTV18 conducted a panel discussion on the issue, but such is Uday Kotak’s stature that not a single panelist was willing to publicly reprimand him and the bank; instead they gave excuses justifying the bank’s conduct. Hence, apart from merely reporting that the bank had filed a writ and that the Bombay High Court had rejected the stay, the business media have been content to sit it out as mere spectators.

The detailed correspondence disclosed by The Wire clearly reveals the partial treatment given to Kotak by the regulator in the past decade. When the RBI finally decided to crack the whip, the rebellious bank took the unprecedented action of taking the regulator to court.

The reason for Kotak’s defiance of the RBI, going so far as to drag the central bank to court, can be understood only in the light of the Kotak group’s corporate structure, which hinges on control of KMB. The short-term gains of such a structure come with long-term risks, something the bank’s promoters do not acknowledge.

As a consequence of this ill-advised gamble, Kotak is now set on a headlong collision with the banking regulator.

Hemindra Hazari is an independent market analyst.

Note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly made references to possible penalties under Section 46(1) of the Banking Regulation Act, which included imprisonment. Although in the RBI Show Cause Notice (SCN) to KMB dated October 29, 2018 published in The Wire on December 26, 2018, highlights issuance under Section 35A, 46 and 47A of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 – non-compliance with RBI directions, para 3 of the SCN specifies Section 46(4)(i) wherein the RBI may impose monetary penalties. Hence in citing Section 46, the RBI is invoking clause (i) of subsection (4) and not subsection (1). Therefore, the possible penalties the RBI can impose on KMB are only monetary in nature.