Rabindra Kishen Hazari Jr.

Napoleon was very short. He was my father’s hero. Dad, Rabindra Kishen Hazari, was also very short, barely 5’3, and he didn’t wear platform shoes.

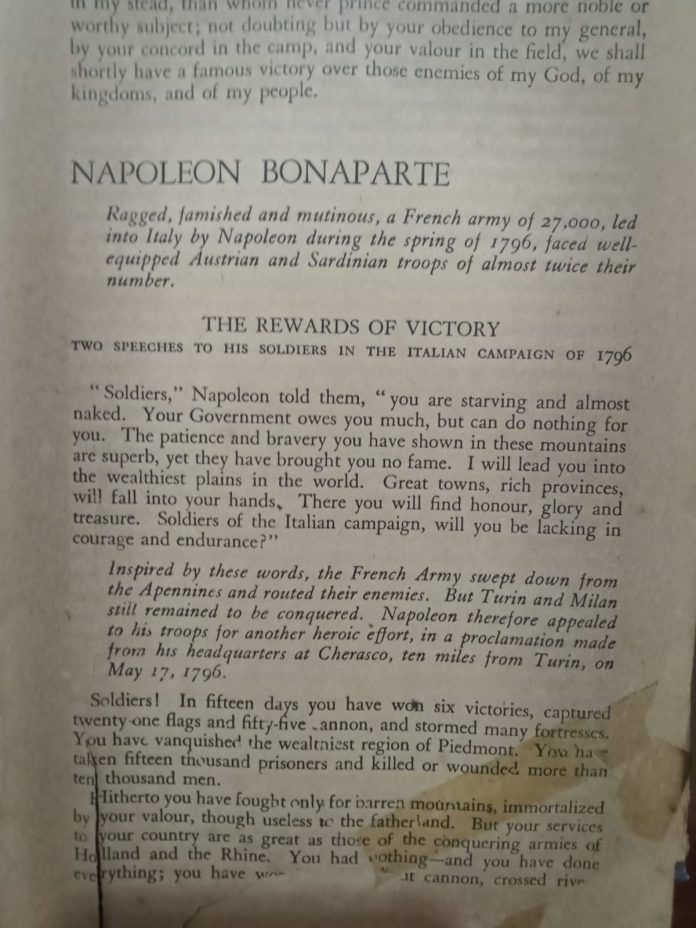

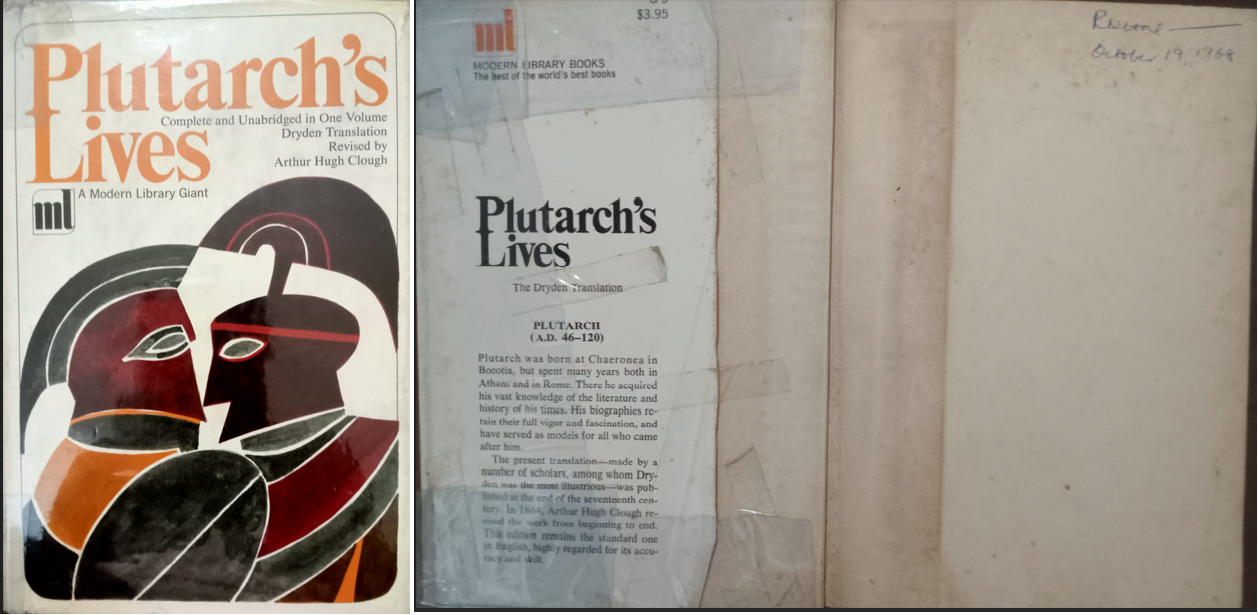

Dad would read out Napoleon’s speeches and those of Cicero, Seneca, Tacitus, Nehru and many others from Plutarch’s Lives and other classics from ever since I can remember.

When I was around 2 to 4 years old, I would wait for Dad to return from his lectures when he was a Lecturer in Economics in St Xaviers College, Bombay, or from New Delhi, where he would be working on Commissions from the Finance Minister.

I would eagerly scramble into Dad’s lap with books which I couldn’t read then but I would point with a grubby finger at various extracts I had marked and have Dad read them to me again and again and again.

Dad would explain and answer my hundreds of questions with incredible patience whilst my mother and grand-mother would scowl and scold me for not letting Dad rest, eat or sleep. I often fell asleep in Dad’s arms midway through these readings and intense quizzing.

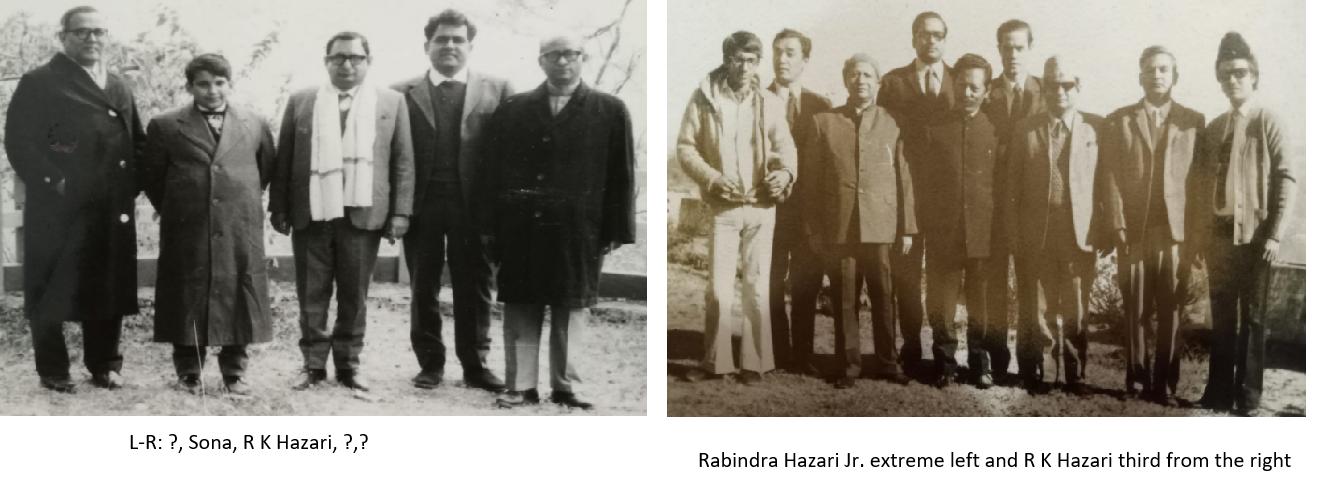

Later, when my younger brother, Sona, and I were older, we would accompany Dad on his private and official trips to some of the most beautiful, remote and most backward places in India; all over the North East, Himachal, Kashmir, the areas which were later hotbeds of insurgency, Konkan, Deccan, Kutch, Rajasthan, Punjab, all over South India, the Sunderbans and tea gardens in the Nilgiris, Assam, Darjeeling and the Dooars, North Bengal, where I much later worked briefly on a summer job whilst in College.

Rabindra Hazari Jr. and Somindra Hazari Accompanying R K Hazari on Trips in the 1970s

My happiest memories of Dad is of listening to his reading out speeches and extracts of famous books, attending his public speeches and travelling with him all over India especially by train and road.

What do you make of this countryside, Dad would ask?

Nothing, my brothers, Sona [Somindra Hazari], Hemu [Hemindra Hazari] and I, South Bombay born and bred, would reply.

Look again, carefully this time, Dad would urge.

What are the houses like? Kucha or pucca?

Are there electricity transmission towers and power cables?

Is there water? Wells, tanks, canals? Pumpsets? Tractors?

That showed whether the land was irrigated or non-irrigated. Tractor meant prosperous farmer.

Roads, dirt or tarred?

Later, the kinds of crops grown; food single crops for sustenance on arid non-irrigated soil, bajra, jowar; whilst wheat and sugar cane are double cash crops on irrigated soils, with huge differences in farm income and rural wealth.

Coconut and fruit bearing trees; these take years to bear fruit. What does the farmer live on until his trees bear fruit? He must have fruit bearing trees already or alternative income. Poor, landless, marginal farmers cannot suddenly start with fruit trees. If they do, it’s often a scam to get farm credit in the names of benamis.

These are the indelible memories of my father who sadly died young, aged just 54 in 1986.

My family still reeling in shock at Dad’s sudden death was at a loss of what to do at his funeral. Dad had warned us umpteen times since we were knee high, when I die, no priests, no prayers, no rituals. We obeyed. None of the above. However, there was a vacuum, we needed something to say or said, some closure.

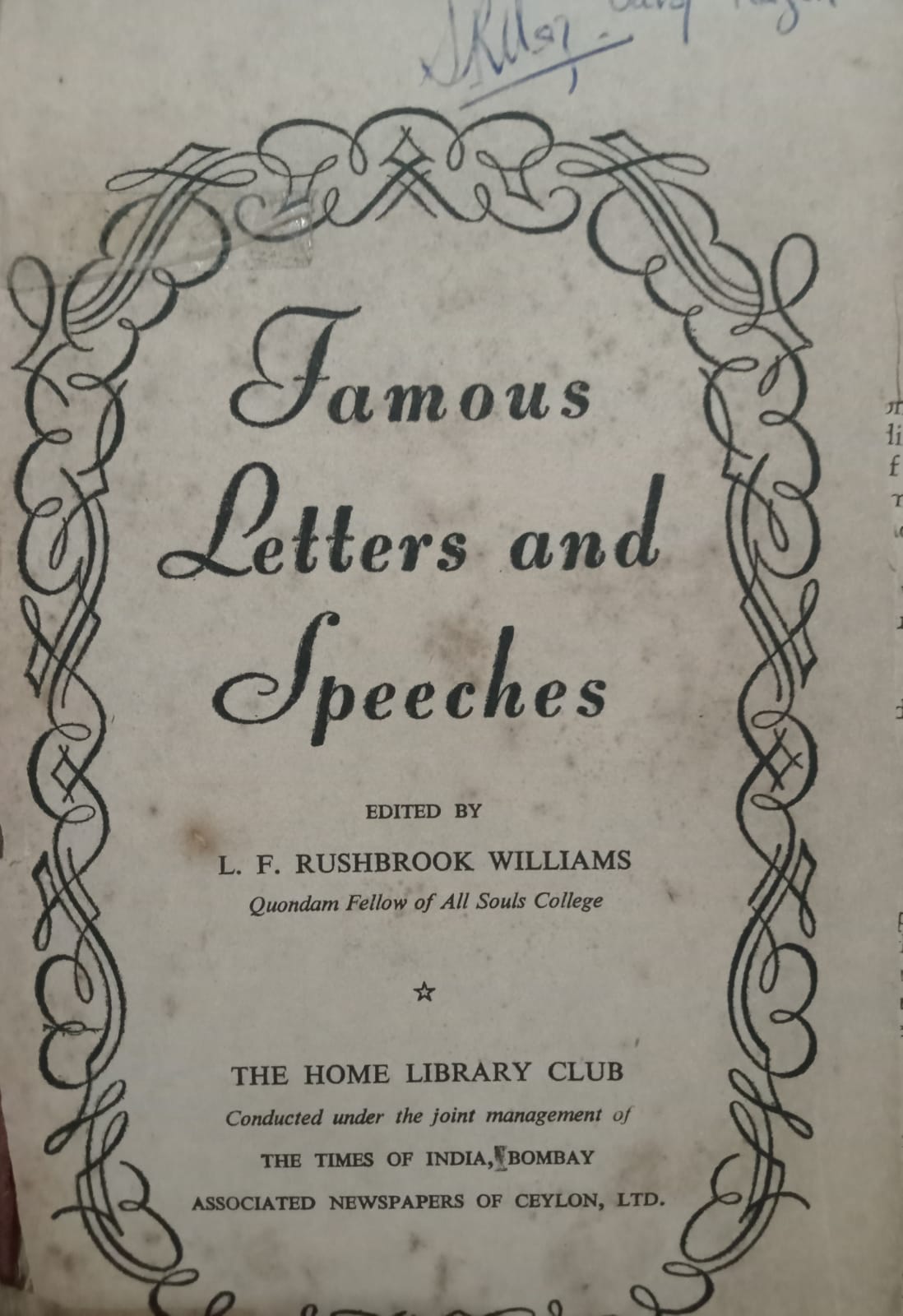

Then I remembered my father’s hero, Napoleon. I pulled out the precious book, “Famous Letters and Speeches”, which Dad would read to us.

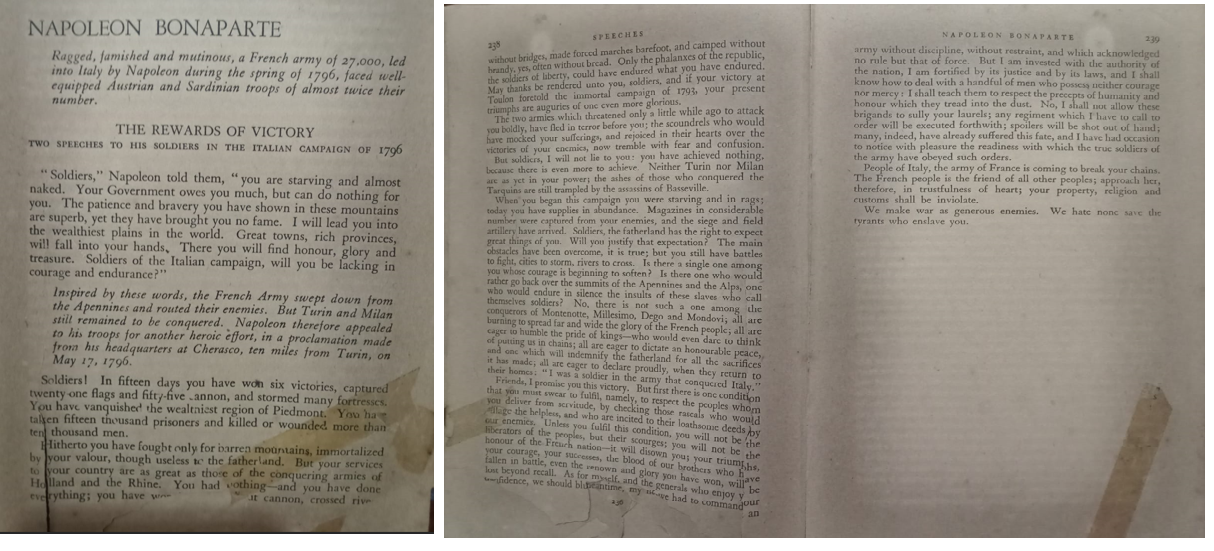

Standing next to my father’s body, I read out his favourite speech, Napoleon’s speech in 1796 at the start of his celebrated Piedmont Campaign, when following Hannibal’s footsteps in the Punic Wars of Carthage [264 – 146 BC] versus Rome, Napoleon did the unexpected and the impossible, he crossed the Alps with a French army of conscripts, peasants and artisans, starved and in rags, and with great valour and brilliant generalship routed several Italian and Austrian armies, conquering Italy.

And so it was with the stirring words of Napoleon’s great speech still ringing like a war mantra in our ears, exhorting us to do the impossible, we said Bye Bye to Dad.