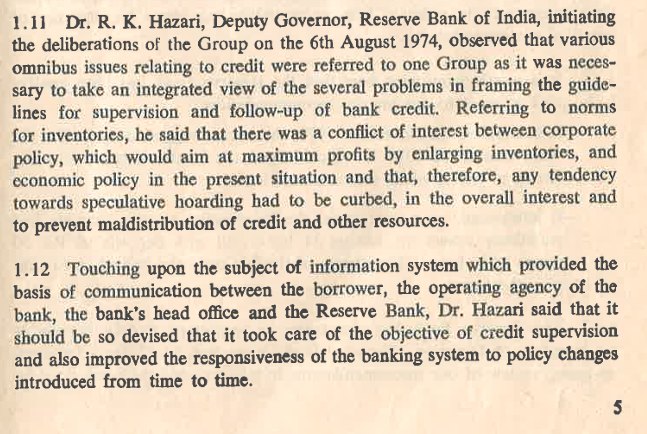

This is an incomplete transcript of a lecture at the National Institute of Bank Management (NIBM) for bankers on April 1, 1985 by R. K. Hazari. The lecture elaborates the historical context of the shift in bank lending from financing trade to financing industry and the need for banks to introduce new systems to finance the working capital of manufacturing companies. R K Hazari was the Deputy Governor (November 27, 1969 to November 26, 1977), Reserve Bank of India and was in-charge of the Department of Banking Operations and Development (the erstwhile DBOD) in the early to mid 1970s and played a pivotal role in the setting up of The Study Group to Frame Guidelines for Follow-up of Bank Credit widely known as The Tandon Committee in 1974.

The best way to begin is, it’s not as if the banks had no system of appraisal before. I think, whenever any new people come in at the policy making level, or new ideas come in, in the first flush, everybody behaves as if there was no management before – That’s not fair. What happens, very often, is that methods that have been evolved in a different environment continue to be used and adopted long after the environment has changed, and the needs of the situation have changed.

…of the literature on banking was concerned with trade financing, and it was therefore appropriate that the methods of lending, the mechanisms of lending, purposes of lending were all attuned to trade finance, where you first of all started with the objective that you are doing self liquidating lending. Why? Because trade, after all, does not deal in goods for their own sake. It does not manufacture. Trade is really a mechanism of adding value by either changing the location, or by bulking transactions, or by desegregating them. Therefore, you do start, when you are financing trade, with the assumption that you are doing self-liquidating lending.

The moment, however, even in trade, you find that the trader is unable to sell his goods — though a trader means a person who buys and sells, he doesn’t, by definition, hold on to the commodities, merely for the sake of holding on. The moment he gets into difficulties, and is unable to sell, well you do have a problem on your hands. But once you move away from trade progressively, as banks in India have been doing since the 1950s, then a change of methods was called for. This has not happened. A lot of people who talk about revolution and banking, and that banks have not changed at all, forget the financing was done ostensibly against pledge or hypothecation of stock, but in fact, against guarantees.

In other words, banks were much more concerned about the worth of the party to whom they were lending to, rather than primarily the transactions that they were financing. It is therefore, not surprising at all that even in the year 1985, when I took an overdraft recently, the kind of credit report that I had to give to my bankers was concerned much more with my assets, rather than with my income or my cash flow. This is a hangover of the past. I am not saying that this was inappropriate at the time when it was framed, it had certain validity. The only thing is that now concepts have changed, and the situation in which you are operating has also changed.

Why has this change come about, and how?

One is that when you start moving away from trade, the cycle of financing becomes longer. In buying and selling also, you can have a longer cycle if there is a seasonality of the commodity. If it’s a commodity like cotton, you certainly have to stock pile at the time of harvest or before, to make the arrangements for financing, and then you dispose off over a period of time.

But generally, these are against established contacts. Once you get into industry the cycle is longer because, in addition, to the normal cycle of trade in the commodity, you also have a cycle of processing and sale of goods with much more of an involvement of fixed costs which you don’t have in trade. As traders only fixed cost is of maintaining his Hindu undivided family at some standard of living, and maybe, of the godown which he does not own in his own name — it is normally in somebody else’s name — he doesn’t have much of fixed costs. Once you get into industry where there is some processing involved, you have a variety, a broad spectrum of fixed cost of one kind or the other, and of that labour is an extremely important element- You also have an establishment which requires accounts and financial controls which in turn, once the scale expands, makes for a certain lumpiness of financing because there is a lumpiness of requirements.

It’s not so in the case of trade. In the case of trade, you don’t want to finance a trader — fine. Tell him to go to the other house, and you get hold of his goods- In the case of an industry, what goods will you really get hold of? His buildings and machinery which you won’t be able to dispose off, or his labour which will be coming on top of your own personal problems at the bank, would be an impossible task to handle? What will you take?

Therefore, in the case of industry, your risks are greater, your cycle is longer and your responsibilities are not merely to the individuals you are dealing with, you become responsible for the employment that is involved in the unit, you get involved in the locality in which you are doing the financing, you get involved with the suppliers, with his buyers, and what not, and your involvements are much greater, and assets by themselves do not provide you with an adequate packing.

Now, if that is so, why is it that we did not perceive these problems for quite some time? The reason was that in any system, it takes a long time for people to see the effect of change, because till then you have a carry over of your earlier wisdom with which you feel you can tackle even the new problems. This is also because the older people who sit in positions of power normally do not know the new concepts, and they insist that the old concepts with which they are familiar should continue to be applicable because those are the only ones that they understand.

What is more, if you think that well change over to new concepts is something easy — let’s face it — it’s not partly because new concepts take time to settle down to become part of the accepted wisdom- They’ll be understood by everybody concerned — they need a different type of information which, as in any other human system, is normally super-imposed upon an earlier system, it does not come instead of it. For quite some time, therefore, you have a mix. Even when you have applied the new concepts of the old system and the new system, it is not as if you get a pure new system altogether.

Many of these problems came to be appreciated in the 1960s because there was a general ferment about having a reformulation of banking objectives and the working of banks. To say this was a passion for socialism is, I think, putting it in very simple language, but it does very little justice to what were involved. The feelings that were reflected in bank nationalisation, or earlier in social control, and which passed off as a passion for socialism, was really far more of a multi-dimensional feeling. One was that bank funds represented a very large part and a very important part of national income and national resources, and just as policies had been framed for allocation and reallocation of resources in agricultural lands, in industrial ownership, in the allocation of industrial markets through industrial licensing, or import and export licensing, or what have you, that there should be some kind of national criteria, rather than purely private or commercial criteria in the management of bank funds.

Furthermore, there was also a feeling that as banking had grown, it was confined only to certain parts of the country and that it was controlled by and for certain sections of the community only. Let me put it very crudely and bluntly — not only was there a feeling that banks were being managed in the interests of a few capitalists, it was also believed that they were managed by and for a few Baniyas in the country, and that those who were outside the Baniya fold, in many parts of the country, did not benefit from banking. This feeling was particularly strong in those parts of the country which had very little banking. It is also the feeling among the rising Green Revolutionaries, who had benefitted from the Green Revolution who wanted economic power consistent with their voting power as also with their technical contribution to the Green Revolution. They wanted more bank funds, they also wanted to be in a political position to have some say in the allocation of bank funds.

There was another dimension involved in the new consciousness about banking, and that was — you might say it was a very limited thing as compared to what I said earlier, but nevertheless, it was important — that banks could be a new force in national development. That through the mechanism of indirect financial control, one could achieve objectives which were not being achieved directly through industrial licensing or control over foreign trade or price controls or physical controls over distribution of commodities. It was believed, in other words, that if you had these major financial controls through banks and financial institutions that you will be able to achieve the objectives far better than through all these direct controls which were quite messy.

Well then, you had this new consciousness about banking, it’s a matter of detail that people felt therefore at the technical level, that one should have a closer look at the purpose and the mechanism of bank lending. You have the first manifestation of that consciousness in that the Heg Committee Report which had a good look at the system of cash credit financing and they came out with the famous idea about hard core which should be financed as permanent requirement and that this should be segregated from the fluctuation portions. Well, this was there, but any new concept takes time. What with all the hurry burry over bank nationalisation, all the other stimulating things that were happening. This did not get much attention, though there was an attempt to get this reflected in credit authorization scope and procedures.

Please remember — and I like to emphasize about this whenever I talk about it — notwithstanding all that very wise, very well articulated literature that you have from American sources, we had almost no available literature — certainly not much experience — of a common method of looking at working capital requirements in bank financing. There’s been a lot of literature and a fair lot of experience in the appraisal of fixed capital requirements by financial institutions by what are called development banks. But till the early Seventies, there was no system for the appraisal of working capital requirements.

American banks claim that they had some system. From what little one has seen of that, I do not think it was a genuine claim either at that time, and I am certainly not convinced about it now. With what experience the American banks have had in so-called working capital financing.

In Britain, they had never been conscious of the problem, and in any case, commercial bank financing of industry in Britain became important only when their borrowers were actually turning sick. It was not a normal feature of their financing.

On the continent, there has been, so far as I know, no major breakthrough in appraisal of working capital requirements by banks. In the Communist economies, nothing of the sort has been known at all.

What the Japanese have been doing over the years, I don’t know. I wonder if there are many people who know. In any case, in Japan, Banks were so inter-connected with industry and trade that one does not know what really the procedures are.

We, therefore, started with a consciousness about the need to have a common system — not something that one bank was trying — but a system common to the entire commercial banking system to be enforced by the Central Banking authority. No other country had tried this. I would say that this has been one of the novel and original features of Indian banking apart from various other features that came after bank nationalisation.

When we became conscious of this problem, as usual, it required a crisis to make the consciousness into something like a spur to action- It required the crisis of 1973 to make everybody sit up. That crisis came about because there was a sudden upsurge of inflation. For sometime one thought that customers were running away with all the bank resources available because under the cash credit system, in any case, the limits sanctioned by the banks were far in excess of the total resources of the banking system, and when there was a rumour — which was fairly well founded incidentally — that there would be drastic restrictions on fresh lending, every customer worth his commercial sense, went and borrowed whatever he could. This led, in other words, to the conditions which were sought to be avoided in terms of the policy of tightening up on credit and it took quite sometime to quieten the situation with the help of those drastic measures that were introduced in July 1974, and as a result of which, between September 1974 and March 1976, India was the only country in the world to have, what was then described, as negative inflation.

Now, for evolving these concepts, when the first credit authorisation forms were introduced in 1970, if I am not mistaken, we had almost no precedents to go by. It was very easy to say that one should lend for a purpose and not lend according to security, but then what exactly is the purpose? How do you assess it? The only thing that we had to fall back upon was the system which Citibank had at that time which was based upon cash flow projections – It was not entirely suitable for our requirements, but we did what we could with it, and so we had the first set of norms for credit authorisation. Till then, I can assure you, while this scheme of credit authorisation had been there since 1965, in fact there was no appraisal either in the Reserve Bank or in the Commercial Banks worth the name – even in the State Banks which had a better system than most others, it was concerned much more with stock-in-trade rather than with projections, and the betterness of the system in the State Bank really related to enforcement of the control rather than the concepts as such.

Well, in 1973, once things had got out of hand, we thought of inventory norms, we thought of a method of lending some change in the cash credit system. Now I would request you to appreciate that those were the days, when discipline was very much in the air. This was before the Emergency, please remember not during the Emergency. This discipline that was sought to be enforced was to be without Emergency powers, but using all the financial powers that the Reserve Bank and the Commercial Banks had acquired by then. After all, the borrowers could not have gone to any other significant source. They had to turn to the banks and the financial institutions.

There was a feeling that while, for priority sector financing, and for financing food and exports, and so forth, there had been reallocation of credit, but that, in the light of the new clientele that was being developed for the banking system, one had to have some kind of rationing to curb up the demand for credit by the larger borrowers. This became even more important after 1973 because the larger part of food financing and of public sector financing was transferred from the Budget to the banks, apart from the greater push that was given later on to priority sector financing. Some mechanism had therefore to be evolved for rationing.

Apart from that, there was also, if you like, the ideological feeling that large borrowers should not continue to have as much of a draft upon bank resources as they have been enjoying for a long time. They should utilise other sources of finance.

In the meanwhile, they must be disciplined. Banking discipline was to be part of a much wider disciplining of the economy which had been done partly through nationalisation of various other enterprises, partly by tightening up on industrial licencing, partly through MRTP [Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, 1969] partly through canalisation of exports and imports, partly also through ceiling on urban lands. In other words, there was a general programme of tightening up as it was described, and of discipline in the economy as a whole. And, therefore, the new bank controls, or controls over working capital financing that was sought to be put in was really part of a much wider control mechanism which vested more powers in the hands of the Government, and in the hands of public institutions then had been thought of before.

Now, I would not presume to tell you all about what the Tandon Committee did, how it reported, but you would notice that there is a stress all through the Tandon Report on discipline, upon information, and upon changing the mechanism of financing, upon getting the borrowers to get more resources on their own. But, to take the principal features, the main contribution conceptually, of the Tandon Report was to say that what is the problem you are faced with? The problem is that there is a working capital gap in the hands of borrower. Funds come in, funds go out, especially if you have a cash credit account.

Therefore, what the banks are called upon to finance is a proportion of the working capital gap. And for that purpose, you have three methods of lending each with a progressively higher contribution by the borrower:

- And this is where I think — and I am subject to correction by those of you because you know the problem much better than I do, and this is where the progress of the Tandon Report really starts — that is, where the first concept is concerned, it is very sound, it explains the purpose of bank lending really speaking.

- You ask a customer for his cash flow projections, and you do the financing in terms of those projections. However, you do not abandon the stock statement, and you do not abandon the concept of drawing power based upon that stock statement. We do get away from the stock statement to the extent that just because somebody is keeping one year’s inventory it does not automatically entitle him to a very large amount of financing subject to whatever margin you might have imposed.

Agree. But please remember that cash flow projection is one concept, the stock statement is a different kind of concept. And, in terms of the report, the mechanism that has been based upon that report – In effect, what you are doing is that you are giving the customer the lower of two things: What projections he makes — subject to your norms and methods — and that traditional drawing power, based upon the traditional stock statement. You will give only the lower of the two. You don’t give the higher of the two. The reason being — now lets get away from the Tandon Report and the concepts for the time being — and you will appreciate it because you have been in operations.

From the Branch Manager’s viewpoint, the projections after all are statistical exercises. All said and done, they are statistical exercises. They are not objective realities. The stock statements from your viewpoint is an objective reality, even though it comes very late, even though we all know the real worth of a stock statement, you also know, I am sure, as seasoned bankers that when a chap’s drawing power is about to fall, he delays the submission of the stock statement And that the valuation of many of the stocks in the statement is, after all, a matter of judgement.

However, from your viewpoint, the first thing you have to ensure is the safety of your own skin. When you have a stock statement, certified by the management in some form or the other, definitely I am saying here are the stocks, you feel much safer with it. If you got to lend only on the basis of projections, in your mind and with the best of reservations that you might have about the stock statement, you still feel that you are taking a speculative view.

For one thing, it relates to the future. The future is based upon something in the past, for after all, it’s a view of the future. Second, while there is something said about variances from the projections, it is one thing to lend on the basis of the stock statement with some known variances, rather than to get involved in variances of a future projection.

And, what is more, since the projection after all is not signed, sealed and delivered with the same documentation as you have with the stock statement, its legal value, after all, is somewhat doubtful. In the case of a stock statement, if you have proof that there is something false in it, you can proceed against your customer. If, on the other hand, in a cash flow projection, you find some inaccuracy one way or the other, well you’ll be told, yes, there was a mistake by a Statistician or an Accountant and that’s the end of the matter. You can’t proceed against the customer in the matter of his projection. Never mind this either.

I would like to draw your attention, while this is fundamental not only at the back of your mind, in your daily life from hour to hour, please remember, the conceptual difference between cash flow and stock statements is very fundamental. Your stock statement in terms of cash flow analysis deals only with the past, and even if your methods of lending and the changes have come into operation, there is an inconsistency between the two concepts. I am sorry to say that while this inconsistency should have attracted the attention of the policy makers in the ten years that have gone by since the Tandon Report was submitted, and later on approved, I don’t think we have ironed out this inconsistency of concepts.

In effect, what you are doing therefore, is you are giving the lower of the two to your customers. And this, I think, is part of the problems that we are having. I remember and Dr N.L. Hingorani [played an important role in the Tandon Committee and was Director NIBM, 1978-1979] would bear me out this question was debated at some length in the Tandon Committee and the continuance of the stock statement was a compromise between the traditional banker members and those who wanted to make a change, led mainly by the NIBM Constituents. My own sympathy was that the NIBM view which wanted a shift much more than the projection, but having executive charge of banker’s morals and morale both, I felt that a compromise of the traditional idea was necessary so that bankers don’t feel lost – So this inconsistency was allowed to remain as a transient feature. It has, however, remained to this day, and I am sorry to find it does not attract the attention which it should have got.

There’s been another problem arising, again conceptually, but it has implications from the way operations have gone on. And that is, while it is true — at least at the back of my mind — and this I used to talk about in the early 70s, but we were very eager to change the system. We used to be very concerned, at that time, about what was called double financing or triple financing of the same stocks, and this was not merely the view of a new element that had brought into banking represented by people of my generation and my ideas but this was concerned by the most seasoned bankers. I remember Mr Kansara [Tribhovandas Damodardas Kansara, chairman and managing director, Bank of India, 1969-1970] of the Bank of India used to say openly in meetings with the Finance Minister present. Sir, we not only do the double financing, we do triple financing. Now, the idea was to delete this. Well, we did evolve a system to delete this, but I don’t think the problem of unpaid stocks being taken out of the stock statement has really been dealt with. It still remains.

But, it’s also a fact that the basis of this whole system has been disturbed — I won’t say undermined, disturbed — by delayed payments that have become the rule rather than the exception in the whole financial system in the country.

The Government does not pay bills in time. Public sector companies do not pay their bills in time. The larger borrowers do not pay their bills in time. It’s a cascade effect. Rightly or wrongly, bankers do not like to do any financing against book debts or bills which are more than six months. Now, one can question that. All that I am saying is at least this is the normal banking standard.

Net result, therefore, is that the customers get into difficulty. Now, bankers led by the Reserve Bank of India can say quite rightly — it’s not the bank’s responsibility to do this financing. But, please remember, that if you are taking the country’s problems as a whole and the borrowers problem as a whole this is a very genuine difficulty that the borrowers have. And while this was there in the consciousness of the Tandon Report, it was believed that this was a passing phenomenon. In fact, it has become an extremely important feature of our financial system all over. And, in fact, these days the railways don’t pay their bills. Post and Telegraph doesn’t pay their bills, not just the public sector, even the Government is not paying their bills regularly.

Thirdly, there was quite rightly the expectation that one would shift over from financing of book debts to bill transactions. In fact, over a period of time, a large part of the cash credit would get replaced by bills and instead of financing book debts or even inventory to some extent, the banks would be financing bills. There was also the expectation that a bill market would be coming up, that had been supported for sometime by the Reserve Bank either rediscountlng bills or refinancing against the security of bills.

In later policies, however, there was a change. It also so happened that there wasn’t enough stamp paper available in many places and of the required denominations. It also so happened that as people, there was a race for socialism in banking as in the rest of the economy, and it came to be believed that a bill market was a capitalist concept, and therefore need not be pursued. And, therefore, again later on, in names of tightening up of the refinance window the Reserve Bank totally stopped rediscount. It discouraged participation certificates, and bills went out. In any case, since delayed payments were becoming the rule rather than the exception, it was difficult to find anybody who would accept bills. Therefore, the change that was expected to take place from book debts to bills did not come about. Therefore, many customers were left with the problem of financing their receivables. They got neither financing of book debts nor did they have bills because bills could not be created.

A fourth matter — taxation. I would request you to appreciate the problem of taxation from a somewhat different angle than it has been usually looked at. Over the years while the Government was ostensibly very stiff about taxation, it also became quite liberal by way of giving tax incentives – Taxation, therefore, was not merely a question of profits left over after tax, it became a matter of larger depreciation because depreciation provisions were liberalised. Tax planning became a lot more important than it had been earlier. Tax planning not only of direct taxes but also of excise duty. The relevance of this was that all these tax planning and tax concessions were related to investment in fixed assets. Therefore, from the borrowers viewpoint, in order to avail themselves of the tax incentives, they had to invest even more than before, even more than they did in the 60’s and early 70’s in fixed assets in order to get the maximum use of incentives and therefore to maximize their cash flow. This meant that their prime concern was to get the margins for fixed assets. There came to be a struggle between having to provide margins for working capital and having to provide margins for fixed assets. Since utilisation or tax incentives was fundamental to business and for growth, companies were naturally much more eager to get the margins for fixed capital than to provide margins for working capital which is what bankers had wanted in terms of the Tandon Report. Now, when they provided adequate margins of fixed asset as required by the institutions, the institutions at the same time refused to accept the implications for method 2 and 3 if you like. So, having inefficient a margin for working capital which is what method 2 and 3 boiled down to, translated into traditional methodology.

Therefore, companies started having problems with having an adequate margin for working capital and they raised a lot of hue and cry about it. The hue and cry came from three different sources: One was the rapidly growing companies which had the best tax planning, and had the best marketing — without the best marketing you cannot have the best tax planning. You got to generate the cash, it’s only then that you can keep it – If you don’t generate the cash from sales, there’s no way of keeping the cash. Because they felt that not only they would be hamstrung for their working capital requirements but that providing of larger margin would reduce their fixed capital growth and also reduce their utilisation of tax incentives.

The second source of complaints was from the companies that were turning sick, which either had cash losses or were having problems of one sort or the other and with indecision having become a fundamental feature all over the place, they could not always get quick relief.

Now, it’s very easy to say sacrifices should be borne here and there but not by the banks. Let’s look at the phenomenon as it has arisen. Then who has to solve what and bear which sacrifice is a different matter. But this was a problem that arose and after all losses — cash losses and sickness or incipient sickness has been a fairly widespread feature in industry. And, at the same time, you could not close down the units because of the employment objective or some other locally important objectives.

Even when they did not have accounts like National Textile Corporation, Coal Mining Authority, by whatever name it was called, and various others, even when they did not have the account, and they had large cash losses, the feeling was the banks must continue to finance them. No question should be asked in effect.

There were also large requirements of various trading agencies, like the Cotton Corp and the Jute Corp which also required large funds, in whose case, the Tandon norms did not apply. But they were trading companies. Nevertheless, this made a difference to the principles involved. Because if you insist that banks should continue their financing even when there are cash losses, then your norms do get disturbed.

Third, was the rest of the channel where companies that may not have been growing rapidly, and which was not sick felt that they were having the worse of all the worlds because the new methods and the new norms were being applied to them alone – Why? Because they were not sick, and, because they were not growing very rapidly, their cash generation was not that good. So they felt they were being penalized for the sake of supporting the others. Now, I am not saying that the banks were at fault in this or the borrowers were in fault — these were the phenomenon that came up.

Furthermore, there was also the additional factor which is not a matter of concepts, it’s a matter of the environment in which one operates. We both know — everybody knows — that in the case of certain borrowers, bankers had instructions to be soft. This has a very demoralising influence on the whole atmosphere of discipline as it is sought to be created because, once you relax your standards where perhaps, there should have been no relaxation then it becomes very difficult to enforce standards elsewhere.

And, on top of this, the kinds of difficulties that have come about, have been made worse by the fact that there was another round of inflation after 1979, which was brought about by the increase in oil prices as also by an extremely bad harvest in 1980. Once there is an inflationary psychology, where your new methods of lending are meant to curb that. Nevertheless, it makes business sense from the viewpoint of the borrower, to stop by somehow or the other. If he expects that either administrative prices or market prices are likely to go up, if you know that steel prices are going up next month, it is an inventory business sense that you stockpile six months requirements if you can. And draw the maximum you can from bank facilities. The next great strain over the economy. And it becomes a typical strain on the method of lending because then it becomes difficult to apply norms.

A second thing that has to be considered is the contribution and the margin. As we were discussing a short while back, what is required is a certain contribution essentially in terms of the Tandon methodology where the margin can fluctuate. This would take away what the borrowers described as arbitrariness or unfairness, but at the same time of peak requirements, they are unable to provide the margin. Now, if the margin were to fluctuate, then it is understandable that at the time of peak requirements, the margin would be somewhat less. This would be particularly true in case of seasonal or contingent requirements where you have a bunching of deliveries, sometimes a bunching of finished goods.

Third, again in terms of spelling out the flexibility — I am trying to pinpoint it — and that also concerns the prior authorization required from the Reserve Bank and therefore from the Head Office of the Bank, for the operations people, how much variance should be allowed in respect of limits? Just now, there is no variance at all permitted. Once something comes in specified categories, the only variance permitted, if I am not mistaken, is Rs 25 lakhs or something of that order. Now this might be alright where the rate is 1 crore, but where the limits are substantially larger, it makes for a lot of loss of time and it requires a fair lot of inputs at all levels plus uncertainties, should there be a wider scope allowed for variances in limits or specified periods of time, special variance if you are competing with the tough statements in a more or less traditional system.