The deregulation of India’s life insurance industry in 2000 and the eventual direct listing of private life insurance companies, with ICICI Prudential Life being the first, offer opportunities for investors requiring exposure to this sector in India. Increasing penetration, enhancing long-term savings and mobilizing much-needed investments for infrastructure were expected to be the outcomes from such a policy. The liberalization process transformed the infrastructure sector from a low risk, public sector asset to a high-risk investment and introduced high volatility in penetration as insurance companies became stock market players and exposed policy holders to the vagaries of the capital market.

For those interested in conventional life insurance companies, they may have to wait indefinitely for the listing of the government-owned Life Insurance Corporation as many private sector insurance companies have adopted a mutual fund model. In the alternative, they may consider some of the companies less exposed to the capital market and may have to wait for the eventual listing of HDFC-Max Life, Bajaj Life and Birla Sun Life.

Objective of De-regulation to Enhance Long-Term Savings for Investment

The objective of deregulating life insurance and allowing the private sector to enter at the turn of the century in 2000, was to increase life insurance penetration (premiums as a percentage of gross domestic product), raise long-term savings which in turn could fund long-term investments, typically in infrastructure, and thereby promote growth in the real economy. Furthermore, it was argued that private sector entry would improve customer service and efficiency.

Earlier, too, the government-owned Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) mobilized long-term savings and deployed substantial sums in long-term infrastructural investments, which benefited the real economy. Infrastructure was then considered a low-risk, low return, public sector asset, in a regime of administered prices. The maturities of life insurance policies were well-matched to the gestation periods of infrastructure projects.

Infrastructure in Liberalization Era Became High Risk

In the current de-regulated environment, however, just as infrastructure has become a high-risk investment, insurance companies have become stock market players. Instead of promoting insurance penetration as such, life insurance firms are directly competing with the mutual fund industry with similar (and probably more expensive) products. Along with the death of the erstwhile development banks, this shift has undermined the stable funding of the infrastructure sector, and left it at the mercy of financialisation and speculative activities.

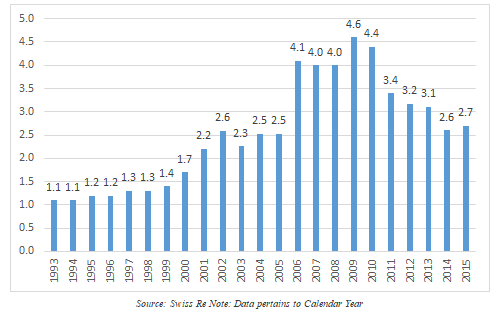

Life Insurance Penetration in India

Disappointing Growth in Life Insurance Penetration

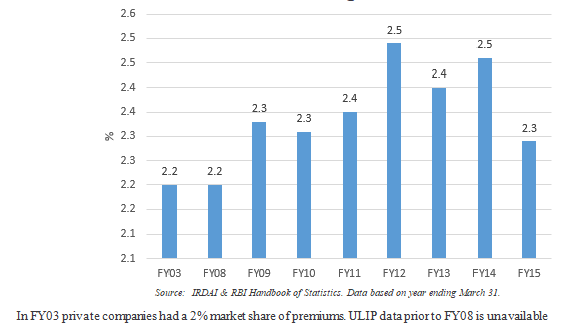

The experience of private sector life insurance in achieving the goals of higher penetration, mobilizing long-term funds and customer service and efficiency has been disappointing. Life insurance penetration in India in 2001, when insurance was liberalised, was 2.15%. This rose to 4.6% by 2009, seemingly a dramatic improvement. But this growth was on account of the surge in the stock market and introduction of Unit Linked Insurance Policies (ULIPs) by the private insurers. Unlike a pure insurance plan, ULIP provides insurance and investment under a single integrated policy, wherein a large component of the premium is invested as a mutual fund product with a small insurance pay-out in case of death. In most cases, the life insurance cover in a ULIP is inadequate to compensate the policy holder’s dependents in case of death. From 2009, life insurance penetration declined to 2.7% by 2015. The reasons: a stagnant stock market, combined with the fall-out of mis-selling and high charges of ULIPs, followed by tighter regulation.

Life Insurance Penetration Excluding ULIPs

In a 14 year span, despite the entry of 23 new private sector companies, life insurance penetration excluding ULIPs is only marginally higher than at the time of de-regulation. One of the main objectives of opening the life insurance sector was to increase the penetration of typical life insurance policies. Even without the entry of private companies, the government-owned LIC on its own could have increased the penetration to these levels based on its earlier track record. Privatisation resulted in massive losses to policy-holders. Even worse, an academic paper in July 2014 estimated the losses to customers due to mis-selling of ULIPs on account of high mortality and other charges between 2004 to 2011 were around US$28bn or nearly 2% of India’s FY2010 GDP. Such staggering losses for policy-holders in an emerging economy was a high price to pay for liberalising and introducing private players in the sector.The extent of mis-selling of ULIPs which took place during this period is illustrated in the Allahabad High Court judgement delivered on May 29, 2014, which severely castigated the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) and the life insurance company. The petitioner in his early 60s invested Rs 50,000 in 2007, in a 5-year ULIP of SBI Life Insurance. On maturity in 2012, when he survived the policy, he was paid only Rs 248, a complete destruction of his investment. The judgement stated,

“he was never informed that even if the NAV [net asset value] rises his entire amount invested in mutual fund will be consumed by the charges amongst which the mortality charge is so high that there was absolutely no chance of getting any amount higher than the amount invested”.

The conduct of the private life insurance companies in this period of rampant unregulated growth was the very reason life insurance was nationalized in 1956. As the then finance minister, C D Deshmukh remarked in parliament,

“…that life insurance today was not managed either efficiently or with an adequate sense of responsibility… The conclusion that finally emerged confirmed our apprehensions. The industry was not playing the role expected of insurance in a modern State, and efforts at improving the standards by further legislation, we felt, were unlikely to be any more successful than in the past. The concept of trusteeship which should be the cornerstone of life insurance seemed entirely lacking…. Even the first examination pointed to nationalisation as the obvious step.” (cited in Aspects of India’s Economy, nos. 26 & 27, November 1998)

Privatisation introduced volatility in performance.

The entry of the private sector and of ULIPs transformed the earlier steady and secular rise in life insurance penetration (1.1% in 1993 to 2.2% in 2001) to a highly volatile development exposing policy holders to colossal losses and the vagaries of the stock market. ULIPs derive value from the underlying investible assets, which in India typically are stock market investments. Such products are influenced by movements in the stock market and are popular during stock market booms, while in market meltdowns investors get adversely impacted. With the tailwind of a booming stock market, private sector insurers found it easier to meet their business targets by selling shorter tenor ULIPs rather than the 15-20 year typical life insurance policies, although the latter are more sticky and enhance long-term financial savings in the economy. Such a strategy assured life insurance employees and distributors of immediate increments and bonuses. In the long-term business of life insurance, private sector companies were depending on short-term products to meet immediate objectives. In the Indian mutual fund industry, more than half of equity assets move out from schemes within 2 years while IRDAI mandated in 2010 that the minimum lock-in period for ULIPs would be 5 years. Private life insurers emphasizing ULIPs not only get tenor funds significantly lower than the 15-20 year annuity premiums associated with regular life insurance but their strategy unravels when the stock market falls or goes into an extended stagnation.

Is the premium profitable segment saturated?

There is perhaps another ominous explanation for the insignificant increase in life insurance penetration even after the entry of so many private sector companies. The profitable premium segment of Indian individuals being financially literate may have already been extensively covered by LIC since nationalisation of life insurance in 1956. LIC may have been cross subsidising to increase low-income insurance penetration, but the deregulation resulted in increasing competition for the saturated premium segment. The private sector normally tends to ignore the marginally profitable or loss-making low-income segment, and LIC, facing competitive pressure in its profitable segment, may have decided to go slow in this segment, where volumes exist but at the cost of profits. This may also explain why large private players have concentrated on ULIPs and not typical life insurance policies as the market in the profitable premium segment may be saturated. Unfortunately, in the absence of dis-aggregated data of ULIPs by region and income segments it is difficult to come to any definite conclusions.

Presently, the largest private insurers are ICICI Prudential Life with a market share of 10%, followed by SBI Life (9%), HDFC Life (7%) and Max Life (4%). Once the HDFC-Max Life merger is finalised it will dethrone ICICI Prudential Life (ICICI PruLife) as the largest private life insurer.

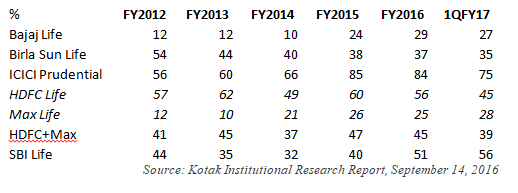

ULIPs Significant Component of Business for Private Insurers

Since inception, the large private life insurers relied on ULIPs to grow their business with ICICI PruLife being an outlier. While some of the private sector life insurance companies moderated their ULIP contribution during FY12-FY14, ICICI PruLife accelerated its ULIP focus. Some of the other large private insurers like HDFC Life and SBI Life still have high exposure to ULIPs. The merger of HDFC Life with Max Life once finalised will result in a lower exposure to ULIPs for the combined entity.

ULIP Contribution to New Business Premium

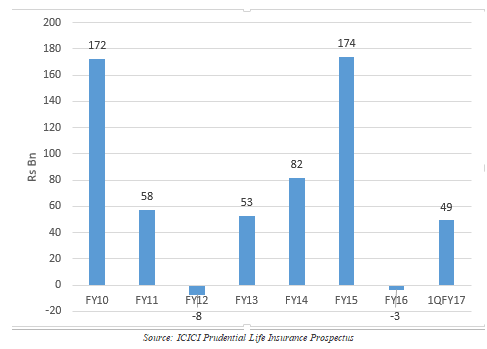

Volatile Performance for ULIP Holders

The fortunes of ULIP holders fluctuated with the market, for ICICI PruLife, the net investment gains (inclusive of unrealized gains) was Rs 172 bn in FY10, plummeted to a loss of Rs8 bn in FY12, soared to Rs174 bn in FY15 and plunged to a loss of Rs3 bn in FY16. The six-year history reveals a roller coaster ride for ULIP holders of ICICI PruLife.

ICICI PruLife: Net Investment Income Inclusive of Unrealised Capital Gains

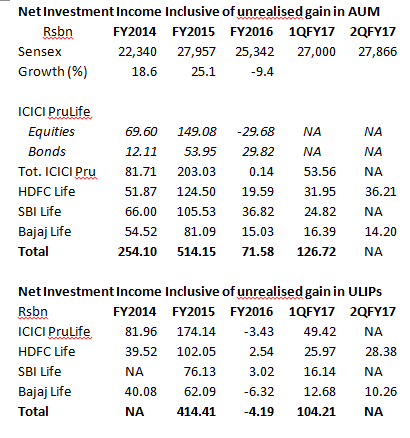

In the last 3 years, the volatility in investment income is mirrored by other life insurance companies as well with a strong performance in FY15 as the Sensex rose by 25% and with FY16 reporting a steep decline as the Sensex fell by 9%. The revival in the stock market in 1HFY17 boosted investment income in the industry.

Source: Companies. NA=Not Available

The investment track record of ULIPs being dependent on volatile capital markets does not inspire confidence to establish a sustainable long-term life insurance business. If like the government-owned LIC, ULIP is a small component of the business (FY15 4.6% of assets under management, as compared with private companies 60.7%), the volatility can be contained to a small segment of customers looking for short-term, high-risk returns.

Contrary to the expectations of life insurance deregulation, some of the large private companies have established their business model on ULIPs, a mutual fund product and in doing so sacrificed the objective of raising genuine life insurance and long-term savings for the economy. In retrospect, the liberalisation of the life insurance sector provided a license to open a casino. For those interested in conventional life insurance companies, they may have to wait indefinitely for the listing of the government-owned Life Insurance Corporation as many private sector insurance companies have adopted a mutual fund model. In the alternative, they may consider some of the companies less exposed to the capital market and may have to wait for the eventual listing of HDFC-Max Life, Bajaj Life and Birla Sun Life.