Where it has powers, the RBI has refused to use them, even when serious lapses in management are detected.

Former RBI governor Urjit Patel. Credit: Reuters

Hemindra Hazari BANKING 20/MAR/2018

Urjit Patel is normally a very reticent man. So much so that as the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor, the individual officially responsible for inflicting the disaster of demonetisation on a hapless Indian public, he maintained an unnerving silence long after the announcement of the measure.

And for a considerable time after the Punjab National Bank scam came to light, he uttered not a peep.

He might have continued to observe his vow of silence had criticisms emanated from only the public. However, when the finance minister too pointed his finger at the RBI for failures of oversight, a stung Patel struck back. In his defence, he declared that the RBI lacks the powers to effectively regulate government-owned banks. For the banking regulator and supervisor, indeed the RBI governor himself, to make such a claim 50 years after bank nationalisation, is quite incredible. This statement needs to be examined carefully, as government banks control nearly 70% of bank assets in India.

Patel’s major grievance is the RBI’s inability to remove directors, including the chief executive officer, merge and/or liquidate government banks. While the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 (BRA) authorises such powers to the RBI for private banks, the Nationalisation Bank Act, 1970 and the State Bank of India, Act, 1955 prevents the banking regulator from doing the same for the government-owned banks.

Patel’s statement is correct on the facts it cites. The problem is, it is not relevant to the issue at hand.

In the case of the PNB fraud, for which the government has publicly blamed the RBI’s lapses, even if the RBI had powers to remove government bank directors, could the regulator have prevented the fraud?

Governor Patel would have a case if the RBI were aware of the issue and had instructed PNB to specifically rectify the loopholes (namely, integrating the SWIFT with the core banking solution [CBS] and reconciling the bank’s Nostro accounts). Had the RBI detected shortfalls in the PNB’s systems, and issued directions which in turn PNB had refused to abide by, it could argue that it requires the powers to remove board members. So far, the RBI, however, has not presented any such evidence of having detected and acted against the fraud. Rather, what is so far known about the fraud is that the senior management at PNB was (apparently) unaware of the fraud, and so was the RBI.

Moreover, in practice, even though RBI does not have the powers to remove the CEOs of government banks, government banks ignore the central bank’s instructions at their peril. The RBI’s confidential inspection reports are taken extremely seriously by not only bank boards, but also by the banking department in the ministry of finance, and bank CEOs have to reply to the ministry regarding how the bank has addressed any shortcomings mentioned in the RBI inspection report.

Reserve Bank of India. Credit: PTI

In its defence, the RBI cited the then deputy governor S.S. Mundra’s speech on September 2016, cautioning banks about fraudulent messages being sent on the SWIFT network and via confidential instructions to banks on at least three occasions since August 2016 on the possible misuse of SWIFT. But as the regulator, issuing warnings is only one aspect, the responsibility lies with the RBI to have ensured that banks and especially PNB had enforced its instructions.

If the RBI had insisted on the implementation of these two measures, the PNB fraud would have been detected at a very early stage.

In the PNB case, even if the central bank had the powers to remove the government banks’ board members, it could not have prevented this fraud as long as it was unable to detect the seriousness of the shortfall in PNB’s internal systems.

The perception created, perhaps unintentionally, by Patel’s utterances is that RBI’s supervision over government banks is inadequate. This needs to be dispelled. Successive RBI governors had never publicly complained about the lack of powers to effectively supervise government banks.

Indeed, C. Rangarajan, the former RBI governor (1992-1997), responding to Patel’s speech, said: “So far as supervision is concerned, there are enough powers, but to take action on the public sector banks, consultations with the government is needed.” The Economic Times, citing an anonymous senior government official, highlighted 13 provisions in the BRA which empower the RBI to take action against government banks and “It empowers the banking regulator to appoint its officers to banks, direct changes in management, inspect any banks and its books and accounts, direct special audits and examine a director or officer on oath.”

Unlike in the private sector banks, a senior RBI official is appointed on all the government banks’ board of directors, and if the RBI director does not approve on any decision, the board is unlikely to clear the proposal. Hence, not only is the RBI representative present but he/she is also the most powerful non-executive director on the board.

Sometimes, politically-sensitive proposals which a bank CEO cannot decline are shot down by the RBI director and the vested interests that backed the proposal are unable to do anything. Such can be the influence of the RBI on the boards of the government banks as it is the banking regulator and supervisor.

The checks and balances in government banks also on account of multiple agencies, some of which are protected by parliament statutes. The Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) representative is in the senior management of government banks. All frauds have to be also reported to the CVC, and, over a certain size, also to the Central Bureau of Investigation. The banks’ subsidiaries come under the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG), and government banks are under the ambit of the Central Information Commission (CIC).

Governor Patel, when alluding to leveling the playing field between the government and private sector banks, conveniently ignored the absence of these institutions in the governance of the private sector banks.

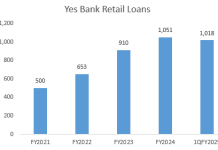

Nevertheless, how has the RBI used its powers of removing board members in private sector banks? In 2017, most of the new private sector banks reported huge divergences in their results. For example, for the year ending March 31, 2016, and 2017, disclosures revealed that the banks had misreported their accounts by understating their non-performing loans and overstating their profits.

In the case of Axis Bank and Yes Bank, the divergences were more severe, as both reported two consecutive years of fudging the books. Mis-reporting of accounting is a serious offence, as it distorts price discovery and valuation of the bank in the capital market, and is a criminal offence under the BRA. Bank officials can be imprisoned for misreporting information. Senior bank officials and auditors who have certified such accounts have no credibility. And hence for such an offence, the RBI should have removed the CEO, the head of the audit committee, the chief financial officer (CFO) and the auditors of these banks.

Yet to date, the RBI has chosen not to do anything, apart from levying a paltry fine on the bank, which is in effect penalises shareholders for the misdeeds committed by the senior management. Thus, where it has powers, the RBI has refused to use them, even when serious lapses in management are detected.

It was unbecoming of the government to have publicly reprimanded the RBI for failing to detect the PNB fraud. Patel’s response not only further lowered the bar but also eroded the credibility of RBI’s supervision over government banks. It is unprecedented for a serving RBI governor’s decisions to be contradicted or criticised by his predecessors, but since Patel’s appointment, Y.V. Reddy went on the record to be critical of demonetisation, and now Rangarajan has publicly contradicted Patel’s views on RBI’s authority over government banks.

Sadly, under Patel’s governorship, the credibility of an institution predating even the emergence of independent India has sunk to its nadir.

As a former CEO of a new private sector bank stated to this writer, “On the rarest of rare occasions when this governor opened his mouth, he put his foot in it.”

Hemindra Hazari is an independent market analyst.