Last Updated : Apr 15, 2019 04:28 PM IST | Source: Moneycontrol.com

By proposing the use of perpetual non-cumulative preference shares to cut promoter holding, Kotak, the promoter, is guilty of not complying with the spirit of the law. So too, Kotak Mahindra Bank and its independent directors.

Ravi Krishnan@writesravi

As the battle between Kotak Mahindra Bank and the Reserve Bank of India over promoter shareholding in the private lender wends its way through the judicial process (the next hearing is a week away), it is clear that there will no winners in this battle. Corporate governance is the big loser.

In the preface to the report of the SEBI committee on corporate governance which he chaired, Uday Kotak wrote: “if one delves deeper (into corporate India), one could find that while the letter of the law may have been complied with, the spirit of regulations has not necessarily been embraced wholeheartedly.”

By proposing the use of perpetual non-cumulative preference shares (PNCPS) to cut promoter holding, Kotak, the promoter, is guilty of not complying with the spirit of the law. So too, Kotak Mahindra Bank and its independent directors.

It’s nobody’s case that the private sector bank has not complied with the letter of the law. According to the RBI’s rules, the bank had to trim promoter shareholding to 20 percent of paid-up capital by 31 December 2018 and 15 percent by 31 March 2020. An issue of PNCPS helps Kotak to achieve precisely that.

Ravi KrishnanDeputy Executive Editor|Moneycontrol

But here’s the rub: It is commonly interpreted that the central bank meant equity capital when it wrote paid-up capital in its regulations. So, the PNCPS issue does not adhere to the spirit. It led RBI to reject this method following which Kotak took the regulator to court, rare if not unprecedented in India.

A bank, whose vice-chairman and promoter, chaired a panel on corporate governance and is also the government’s go-to person to clear the IL&FS mess, should be held to a higher governance standard. Remember also, that the promoters have benefited by holding on to ownership, though that is partly thanks to rising share prices of private banks. A stake dilution if it had happened through an issue of shares would have likely depressed prices. Independent Hemindra Hazari had calculated that notional gains to the promoters totalled Rs 15000 crore, a number which Kotak has disputed.

It is true that the RBI also will not come out looking smart whatever be the high court’s decision. It has changed ownership norms repeatedly without providing any empirical evidence (at least publicly). Diversification of ownership hasn’t really prevented governance problems at other prominent private sector lenders such as Axis Bank and ICICI Bank. Currently, the RBI rules on ownership are at variance with other laws (eg voting rights are capped at 26 percent while the economic ownership ceiling is 15 percent). Lastly, the drafting of regulations has been sloppy. Why should equity capital or paid-up capital be left to interpretation?

Clearly, it is time for the central bank to re-visit these regulations. Its on-tap bank licensing guidelines have found no takers. Even in banks with well-diversified shareholding, boards have remained beholden to superstar CEOs. Higher economic interest–or more skin in the game–for more promoters could actually improve corporate governance. In any case, a debate is needed on the issue.

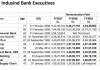

That said, the correct way for Kotak would have been to lobby the regulator and the government for a change in laws. Open lobbying is preferable to exploiting a loophole in regulations. In any case, as other commentators have pointed out, the central bank has given Kotak repeated extensions of the deadline to cut promoter stake. In June 2012, it said promoter holding was to be trimmed to 20 percent by 31 March 2018 and 10 percent by 31 March 2020. Later in February 2017, it revised these to 20 percent by 31 December 2018 and 15 percent by 31 March 2020.These repeated extensions had given Kotak Mahindra Bank ample time to trim promoter stake in equity capital. The fact that it did not do so suggests that the bank did not care for regulatory diktat or that it hoped to get another extension. That does not reflect well on the bank and indeed, Indian banking regulations.

First Published on Apr 15, 2019 12:55 pm