13 Sep, 2020

Zia Khan Gaurav Raghuvanshi Mohammad Abbas Taqi

India’s state-owned banks have lagged behind their private-sector peers in tapping equity capital markets so far this year and are likely to remain dependent on government capital injections amid depleted market valuations and rising bad loans in a pandemic-battered economy, analysts say.

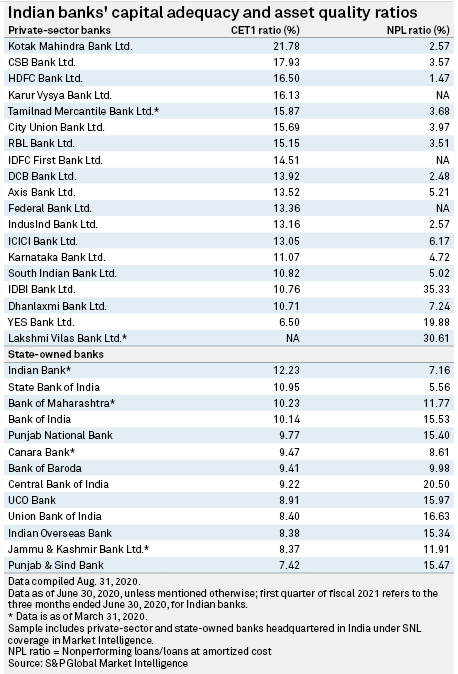

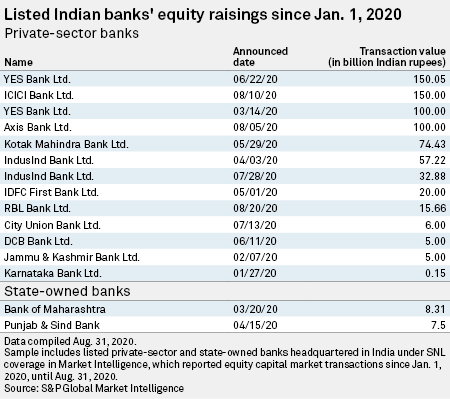

The country’s private-sector banks, including YES Bank Ltd., ICICI Bank Ltd. and Axis Bank Ltd., have raised more than 700 billion rupees in share sales since Jan. 1, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data, compared with share sales by two state banks totaling nearly 16 billion rupees. Except for Yes Bank and Lakshmi Vilas Bank Ltd., all private lenders reported common equity Tier 1 ratios higher than 10% as of June 30, and more than half of them had nonperforming loan ratios of below 5%. In contrast, most state-run banks reported CET1 ratios of below 10%, and all of them posted NPL ratios of more than 5%.

India’s state banks need billions of dollars in capital to bolster their balance sheets. They need 350 billion rupees to 400 billion rupees as additional capital in the fiscal year ending March 31, 2021, to support an estimated 4% to 5% credit growth, said Nikita Anand, credit analyst at S&P Global Ratings.

“Besides State Bank of India and a few other large public-sector banks, we believe many public-sector banks will remain dependent on the government — or government-owned enterprises — to raise capital, given low market valuations and a potential crowding out effect stemming from the size of capital raisings already in the market,” Anand added.

Sandeep Upadhyay, CEO of Centrum Infrastructure Advisory, says state-run lenders need to raise between US$20 billion and US$25 billion over the next two years, based on the banks’ expected nonperforming asset position over the next 12 to 18 months. “Given the subdued financial climate emerging post pandemic outbreak, most of the capital to be raised by the state-run banks is likely to come from the government,” he said.

Limited options

Capital infusion by the government may be hard to come by as a shortfall in revenue collection, especially goods and services tax, has left the government’s coffers strained. The government’s fiscal deficit reached 8.213 trillion rupees in the first four months of fiscal 2020-2021, exceeding the projection of 7.96 trillion rupees for the entire year. The federal government has faced protests by state governments that have not been paid their share of tax income and are finding their own budgets strained as a result.

India faces challenges in reopening the economy as coronavirus infections continue to surge after a nationwide lockdown in March plunged the economy into its worst contraction on record. GDP contracted 23.9% year over year in the June quarter, the worst contraction by a major economy during the pandemic. Banks are expected to bear the brunt of the economic distress, with the Reserve Bank of India predicting nonperforming loans to surge to as high as 14.7% by March 2021 under its “very severely stressed” scenario, from 8.5% in March 2020.

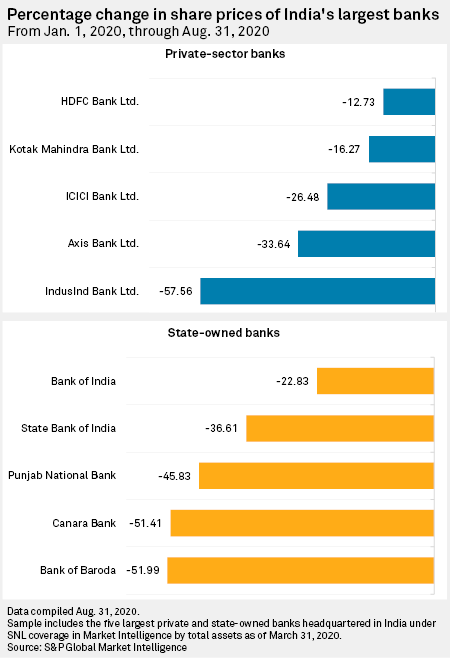

Analysts believe the state-run banks’ options to raise money in the capital markets are limited as their share prices have generally been low so far this year, especially after the pandemic-related uncertainties hit the markets. Shares in banks have declined from 12% to more than 50% between Jan. 1 to Aug. 31, according to Market Intelligence data. IndusInd Bank Ltd. and Bank of Baroda, for instance, saw their share prices drop 57.56% and 51.99%, respectively, followed by Canara Bank with a decline of 51.41%.

Depleted valuations remain a major concern for raising funds for some of the mid-sized public sector banks, Upadhyay said. While investors’ response to share sales by private banks has been encouraging and demonstrates continued interest in the banking sector, a similar response for state banks is uncertain due to inherent challenges around their aggravated nonperforming asset positions and the slow decision-making process, he added.

Privatization, consolidation or reforms?

Given state banks’ challenges, analysts say that the Indian government should implement governance and leadership reforms, strengthen banking regulations and further empower regulators instead of selling the banks or pursuing another round of consolidation.

“In the middle of a slowdown, privatization is the worst strategy as the private sector is less willing to invest,” said Hemindra Hazari, an independent analyst. “In a slowdown, only government and government-backed entities can play a countercyclical role.”

Rupa Rege-Nitsure, chief economist at L&T Finance Holdings, said she is not sure whether selling majority stakes in state banks will bring in better outcomes, citing the increased reporting of scandals and irregularities in some of the systemically important private-sector banks in recent years. Instead, it should grant more autonomy to regulators, strengthen regulations and control non-developmental political intervention, she added.

“We need not privatize [public-sector banks] but [the government] can gradually reduce its stake below 51% by exploring different choices like preferential shares, golden shares and differential voting rights at lower levels of holding so that these banks can be effectively used as tools for developmental policies in general and countercyclical policies in crises, in particular, without hurting their business viability,” Rege-Nitsure said.

As of Sept. 11, US$1 was equivalent to 73.42 Indian rupees.

This S&P Global Market Intelligence news article may contain information about credit ratings issued by S&P Global Ratings. Descriptions in this news article were not prepared by S&P Global Ratings.