Critics say his rise is symbolic of a system where too much power is in the hands of too few

Stephanie Findlay in New Delhi and Hudson Lockett in Hong Kong NOVEMBER 13 2020

When the Indian government approved the privatisation of six airports in 2018, it relaxed the rules to widen the pool of competition, allowing companies without any experience in the sector to bid. There was one clear winner from the rule change: Gautam Adani, the billionaire industrialist with no history of running airports, scooped up all six.

His clean sweep was met with outrage. The Kerala state finance minister said Mr Adani winning the 50-year lease to operate the Trivandrum International Airport was an “act of brazen cronyism” that showed how the central government favoured politically connected tycoons. India’s aviation minister replied that the open bidding process was carried out in a “transparent manner”.

Overnight Mr Adani became one of the country’s biggest private airport operators. He is also its largest private ports operator and thermal coal power producer. He commands a growing share of India’s power transmission and gas distribution markets, and this year announced that his renewables arm Adani Green Energy would invest $6bn to build solar plants with a capacity of 8GW, one of the largest renewables projects in the world.

Along with Reliance Industries chairman Mukesh Ambani, Mr Adani is today one of the most visible tycoons in the country, whose prominence has accelerated in the years since Narendra Modi was elected prime minister in 2014. Like both Mr Modi and Mr Ambani, Mr Adani comes from the western state of Gujarat, where he was a key supporter of Mr Modi and his ruling Bharatiya Janata party as it rose to dominate national politics.

When Mr Modi took office, he flew from Gujarat to the capital New Delhi in Mr Adani’s private jet — an open display of friendship that symbolised their concurrent rise to power. Since Mr Modi came into office, Mr Adani’s net worth has increased by about 230 per cent to more than $26bn as he won government tenders and built infrastructure projects across the country. “Nation building” is Mr Adani’s motto and he likes to talk about helping India achieve energy security.

But as New Delhi accelerates its privatisation drive to offset the severe economic shock of the coronavirus pandemic, Mr Adani’s mushrooming empire has become a focus of criticism for those who believe that capital is being concentrated in the hands of a few favoured corporate titans at the expense of India’s middle class.

Some argue the concentration of economic power in family-run conglomerates is a way to fast-track India’s economic development, like the chaebol did for postwar South Korea. But critics say the rapid consolidation of state assets is creating monopolies and stifling competition.

“Is India going to move towards the east Asian model or the Russian model? So far the tendency looks towards the latter [more] than the former,” says Rohit Chandra, assistant professor of public policy at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. “It’s not clear whether India’s concentration of capital will lead to the long-term benefit of Indian consumers.”

Whether India’s industrialisation leaves it more closely resembling the US at the turn of the 20th century when the likes of oil magnate John D Rockefeller wielded vast influence, or Russia in the 1990s, Mr Adani’s voracious appetite for dealmaking and political instincts have ensured he will play a central role.

“Gautam Adani is very powerful, very politically well connected and very astute at using that power,” says Tim Buckley, an energy analyst based in Australia who tracks India. “He is Modi’s Rockefeller.”

The Adani Group declined to comment for this article.

Beyond Gujarat

The meteoric rise of Mr Adani started when he offered support to Mr Modi in 2003. At the time, the politician — then chief minister of Gujarat — was being heavily criticised for failing to control violent riots that had rocked the state a year earlier.

More than 1,000 people died, most of them Muslims, and Mr Modi was being shunned by India’s business elite and the world — he was barred from entering the US for almost a decade until he became prime minister.

But when some of the country’s most powerful tycoons grilled him onstage over the deaths at an event hosted by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), Mr Adani broke ranks with the old business elite, potentially risking his future for the under-fire politician.

The businessman then helped set up a new industry body to sideline the CII and was behind Vibrant Gujarat, a glitzy biennial summit that would introduce Mr Modi to the world stage and cement his reputation as a pro-business leader. The gamble paid off for Mr Adani, a plain speaker who sets himself apart from the corporate establishment in Mumbai by dividing his time between the company’s headquarters in Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s largest city, and New Delhi, the Indian capital.

“These are new Indians running the government, they have a completely different view of the world and their view is very local,” says an executive present at the acrimonious 2003 event. “Old relationships have flowered and flowered because these are the people they [the government] feel comfortable with.

“Adani was big time in Gujarat and now he’s spreading his wings,” he adds.

Mr Adani, 58, is a rarity among the ranks of Indian dynasts: he is a self-made man, born into a family of eight that practised Jainism, an Indian religion that emphasises ascetic beliefs. After dropping out of college to try a career in Mumbai’s diamond industry he moved back home to import plastics for manufacturing, a business that would lay the foundation for his conglomerate.

In the late 1990s he won the rights to operate Mundra port, located on the mangrove-lined Gujarat coast on the Arabian Sea. He expanded terminals and gained scale, using the cash from operations and a gift for navigating Indian bureaucracy to acquire and develop other ports.

Since then, he has taken on large amounts of debt to build a pit-to-plug vertically integrated power supply chain and a portfolio of businesses spanning defence to data centres and even apple farms in the mountainous state of Himachal Pradesh.

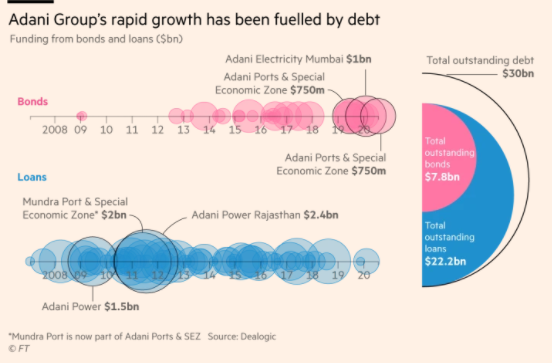

The Adani Group’s total outstanding debt came to more than $30bn as of November 11, according to data from Dealogic, including $7.8bn worth of bonds and $22.3bn in loans. High debt is nothing new among Indian conglomerates but the Adani Group’s rapid expansion has raised concern.

Credit Suisse warned in a 2015 “House of Debt” report that the Adani Group was one of 10 conglomerates under “severe stress” that accounted for 12 per cent of banking sector loans. Yet the Adani Group has been able to keep raising funds, in part by borrowing from overseas lenders and pivoting to green energy.

“Groups that are perceived as politically connected can still tap the banks for loans,” says Hemindra Hazari, a Mumbai-based banking analyst. “If you are any other highly stressed group, then it is difficult for you.”

Going green

The latest front Mr Adani has opened in his quest to dominate Indian infrastructure is renewables, which serve the dual purpose of supporting Mr Modi’s “self reliant India programme” to help overcome the economic shock of the pandemic and of helping to rehabilitate his image with environmentalists.

His Carmichael coal mine project in Australia was the target of a massive campaign that depicted him as a climate change villain. Teenage environmentalist Greta Thunberg received more than 70,000 likes on her tweet in January calling for people to #StopAdani. The mine project — which was initially valued at $16bn — is going ahead, though some investors are dropping out as boards get stricter on sustainability targets.

While it has been a good year for India’s solar sector, Adani Green Energy stands head and shoulders above its peers. The value of Azure Power, a rival listed in New York and valued at about $1.4bn, has climbed almost 130 per cent this year. Adani Green, which has pledged to build 25GW in renewable power by 2025 has soared 440 per cent, giving it a market capitalisation of almost $20bn.

Mr Adani’s personal stake in the solar unit is valued at $13.9bn and, once liabilities are accounted for, amounts to about half of his net worth, according to analysis from Bloomberg.

International investors are paying attention. In February, French energy group Total SA announced it was investing $510m in Adani Green. But a banker who has followed the Adani Group for more than a decade at a US investment bank questions Adani Green’s market valuation in light of its low liquidity, with barely $2m in shares traded a day.

Adani Green, which has yet to record a profit and tapped international debt markets for $863m in funds last year, according to Dealogic, is an example of the Adani Group loading up on leverage to finance expansion. New ventures in the past have been underpinned by Adani Ports. Analysts note that the Adani Group has taken measures in the past year to reduce reliance on what the banker calls “funding arbitrage”, a common tactic for Indian tycoons in which bonds issued by profitable arms help fund new ventures.

Mr Adani continues to enjoy ample access to capital, both at home and overseas, and can tell investors that he has never defaulted on a loan despite highly leveraged balance sheets. Adani Group companies tapped international debt markets with bond sales of more than $2bn and Adani Gas sold a 37.4 per cent stake to Total for a reported $600m, which gave him ample cash flow to weather the shock of the pandemic when it hit.

And international groups are queueing up to partner with the mogul. Earlier this month, Adani announced a strategic collaboration in hydrogen and biogas with Italian gas and infrastructure group Snam.

Mr Chandra says the foreign companies are relying on connected business leaders to navigate India’s volatile regulatory and tax landscape. “This capital is going to favoured companies, not because they deserve it, but because they are the ones that can mediate [the regulatory environment],” he says.

Growing risks

The ascent of the Adani Group has been plagued with controversy and allegations ranging from fraud to environmental abuses. In February, it pleaded guilty to misleading the environmental authorities in Australia over land clearing at the Carmichael mine site and was fined A$20,000.

Along with a group of other companies, it is also being probed by India’s Directorate of Revenue Intelligence in connection with allegations of over-invoicing billions of dollars worth of coal imports from Indonesia. The Adani Group has in the past said it “strongly denies the allegations of overvaluation”.

The company has also been dogged by claims that it has been on the receiving end of preferential treatment in regulatory decisions that have made otherwise risky projects much more attractive.

One claim relates to the Godda coal-fired power plant under construction in Jharkhand state, which plans to import coal from Australia and export power to neighbouring Bangladesh, a country with an excess of coal plants in the pipeline.

Analysts estimate that Adani Power will charge customers more for Godda’s electricity than other plants in Bangladesh and India. The office of the state accountant general warned in a leaked audit report that the higher tariffs represented “preferential treatment” that would result in “undue benefits”.

In the final months of Mr Modi’s first term in 2019, New Delhi gave the green light for Mr Adani’s plant to be declared a special economic zone, a designation that comes with significant tax benefits. Godda became Adani’s second SEZ after Mundra port.

Opponents have filed a petition in the High Court of Jharkhand against the state government alleging that Adani Power acquired the land on which Godda is built for private use and that the transfer violates ownership rules protecting tribal groups living in the area.

Adani Power using the land to build Godda is “completely illegal, void and arbitrary”, argues Ranchi-based human rights lawyer Sonal Tiwary. “The whole profit goes to Adani, the people of Godda don’t receive anything.” The state government has not filed a counter affidavit yet.

In response to land acquisition allegations, Adani Power said in a statement earlier this year that the land was acquired “within the rules”. It added that it “had not made any requests to the Government of Jharkhand to alter energy policy rules or provisions”.

Political risk

The Adani Group’s expansion has become even more marked as the pandemic ravaged India’s economy. The country’s gross domestic product is expected to contract by around 10 per cent in 2020, with the weight of Covid-19 cases seemingly ruling out a swift return to normality.

Though India’s sovereign debt rating is at risk of a downgrade to junk status — a result of the pandemic which has killed more than 127,000 people and infected over 8.6m in the country — few think Mr Adani’s access to capital will face serious constraints.

Abhishek Tyagi, a senior analyst at Moody’s, says for large corporates like the Adani Group, “there are other avenues for raising capital”, including partnerships with the likes of Total as well as domestic banks and financial institutions.

“A number of corporates which are in high yield do access [international] debt capital markets, even in India,” he adds, pointing to a $1.4bn bond issued by Vedanta, the Indian mining company, in August.

The question is whether Mr Adani can maintain the extent of his interests in Indian infrastructure, with some suggesting his political connections could become a liability. “If Modi loses on election day 2024, you’ll see the [Adani] stocks will correct immediately,” says an investment analyst in Mumbai. “If your protector gets dislodged then you lose access to that capital.”

But for others, Mr Adani has become too big to fail. “He’s become one of the most powerful men in India in the space of 20 years,” Mr Buckley says. “What he touches turns to gold.”