13 Jan, 2021

- Author

- Gaurav Raghuvanshi

Investor aversion and strained government finances could complicate the capital plans for some Indian banks, particularly state-owned ones, after the central bank’s latest stress tests indicate that some lenders’ capital could fall below minimum regulatory requirements this year in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic.

As forbearance measures to help businesses and individuals survive the pandemic end on March 31, analysts expect nonperforming assets to spike later this year. The Reserve Bank of India, or RBI, reiterated that, overall, banks have sufficient capital even in the severe stress scenario. The outcome of the stress tests are not its forecasts, but conservative assessments under hypothetical conditions, according to the RBI’s biannual Financial Stability Report published Jan. 11.

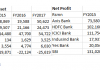

In the baseline scenario, the gross nonperforming asset ratio of the entire banking system could rise to 13.5% by September from 7.5% a year earlier, according to the central bank. If the macroeconomic environment worsens into a severe stress scenario, the ratio could surge to 14.8%, the RBI said.

Among all bank types, state-owned banks could be hit the worst, with their gross NPA ratio potentially rising to 16.2% from 9.7% over the same period, the central bank said. Private-sector banks are likely to fare better, with stress tests indicating their NPA ratio to rise to 7.9% from 4.6% in September 2020. In the severe stress scenario, state-run lenders could face NPA ratio of as much as 17.6%, while their private-sector counterparts could see an NPA ratio of 8.8%.

“We believe that there is a very high likelihood that [the] government will provide further capital to the public sector banks, if needed,” said Nikita Anand, associate director for credit risk in emerging markets at S&P Global Ratings. “Investors and other stakeholders see these measures as necessary for bolstering the resilience of institutions and instilling confidence that these companies can withstand the economic slump.”

Many banks, especially large private-sector lenders and some nonbanking financial companies, have already raised capital in the last two quarters, Shibani Sircar Kurian, the head of equity research at Kotak Mahindra Asset Management Co. said in comments emailed to S&P Global Market Intelligence. “These banks today have capital adequacy ratios in excess of the regulatory requirements and appear to be well placed even after factoring in a rise in [nonperforming loans],” she said.

Capital challenges

State-owned banks, which have largely been relying on the government for capital, may face greater trouble raising funds amid strained government finances.

Those lenders, many of which have lower price-to-book ratios, “will find it difficult to raise capital from the market,” said Hemindra Hazari, a Mumbai-based independent banking analyst. “It is imperative for the government to capitalize [state-owned] banks. It’s their responsibility as a shareholder,” he said.

The government is strapped for cash as its revenues are trailing estimates, limiting its ability to pump-prime the economy. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman faces a tough balancing act on Feb. 1 when she presents the federal government’s budget for the year starting April 1.

A silver lining, however, is that the economy appears to have bounced back faster than initially expected. While India slipped into its first technical recession on record in the July-to-September quarter, the government’s statistics office expects full-year GDP contraction to be 7.7%, shallower than most analyst estimates. Various indicators of economic recovery, including proprietary indexes compiled by Nomura and Jefferies, have reflected improvement after new COVID-19 cases showed a declining trend from a September peak. The National Statistics Office said Jan. 7 that it sees a “resurgence of economic activity.”

Restoring profitability

A few large public-sector banks were able to tap the markets and raise capital recently, which “bodes well for the segment,” Kotak’s Kurian said. “The need of the hour is for the government to continue with the various reforms related to [public-sector] PSU banks in order to ensure that these banks return to the path of profitability.”

State Bank of India raised 40 billion rupees of Tier 1 capital notes in July 2020 as part of a 140 billion rupee capital offering in two tranches. The overall amount raised by state-owned lenders via qualified institutional placements and bond issuance doubled in the year that ended March 2020 over the previous year. Between April and November 2020, the amount raised via private placements had surpassed the previous year’s figure, according to the RBI. However, depressed valuations have led public-sector banks to largely abstain from public issuances, it noted in a Dec. 29, 2020, report.

The government proposed to infuse 700 billion rupees in state-run banks in 2019, taking the total capital support to 3.16 trillion rupees in the last five years. In the current fiscal year, the government has earmarked 200 billion rupees for capital infusion into the state-owned banks, in addition to the lenders’ capital raising from other sources.

Pandemic response

The RBI in August allowed a one-time loan restructuring for stressed borrowers to soften the impact of COVID-19 that allows lenders to avoid classifying those loans as nonperforming assets. The government also announced a 3 trillion rupee emergency credit guarantee scheme last year for small-to-midsize enterprises in 26 stressed sectors that could help borrowers avoid restructuring their loans.

“The RBI has already given banks freedom to restructure the bad loans. … That can mitigate the NPA stress and give time to borrowers to revive,” said Sameer Narang, the chief economist at state-run Bank of Baroda.

India’s banking system faced the pandemic with relatively sound capital and liquidity buffers built in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and supported by regulatory and prudential measures, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das said in a foreword to the central bank’s report. “Notwithstanding these efforts, the pandemic threatens to result in balance sheet impairments and capital shortfalls, especially as regulatory reliefs are rolled back,” Das said.

Maintaining the health of the banking sector remains a policy priority and preservation of the stability of the financial system is an overarching goal of the central bank, he said.

As of Jan. 12, US$1 was equivalent to 73.26 Indian rupees.