Hemindra Hazari

There are high hopes that Urjit Patel, the new RBI governor will act to revive bank lending and thereby do his bit for the economy. But that would require him to make the right diagnosis in the first place. The recently released RBI Annual Report at least shows no sign of that. At the same time, there is a worrying silence from the RBI regarding danger signals in two areas – lending to stressed sectors and retail loans.

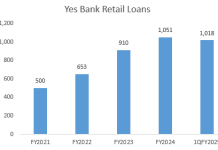

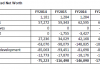

Despite India being the fastest growing economy in the world, the growth of bank credit in India has been anaemic. Non-food credit growth in percentage terms has not crossed double digits in the last two years: in Financial Year (FY)2015 it was 8.6%, followed by 9.1% in FY2016 and for the period ended June 24, 2016 it further decelerated to 7.9% (year-on-year). Commentators, including the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) have attributed the poor credit off take to banks being reluctant to lend to delinquent corporate borrowers and high-stress sectors such as infrastructure, instead preferring to lend to sectors that have superior asset quality, such as retail loans. Personal loans, in stark contrast to corporate and overall credit growth, reported strong gains, with growth rates of 15.5% in FY2015, 19.4% in FY2016 and 18.5% for the period ended June 24, 2016 and stood at Rs 14.4 trillion, which is 22% of non-food credit.

Leverage in corporate India is within limits

The RBI, as well as many analysts in the capital market, say the problem is a ‘balance sheet issue’: that is, highly stressed and over-leveraged large corporations are constraining bank credit growth. The solution implied is the cleaning up of bank balance sheets through aggressive bad loan recognition and recovery (Asset Quality Review, Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets et al), tight control on inflation and continued reforms to create investment opportunities. With these steps, the hope is that corporate credit growth will eventually revive.

But is the diagnosis right? Despite the justifiable publicity given to the high leverage of large, over-extended Indian business houses (Credit Suisse’s critically acclaimed research report, ‘House of Debt’), the Indian private corporate sector in its entirety is not over-leveraged. Indeed, the RBI’s own data in its Financial Stability Report (FSR) shows that for 1,800 to 2,600 select non-government non-financial companies (NGNF), the long-term debt to equity ratio was only 0.38 for the period ended March 31, 2016 – not only was it significantly below 1 but it had marginally declined from 0.39 in the period ended March 31, 2015 and in the period ended June 30, 2015. A study by J Dennis Rajakumar (Economic and Political Weekly, October 31, 2015) has used RBI data to argue that Indian corporate leverage is not high: the long-term debt equity ratio for a much larger sample of 4,388 NGNF companies was 0.44 for the year ended March 31, 2014. Even the total (long and short term) debt equity ratio “remained less than unity” in the entire five-year period ending March 31, 2013.

The RBI under governor Raghuram Rajan (who retired on September 4) had continued to emphasise the over-leveraged nature of select large companies which are a major problem for Indian banks while inexplicably ignoring the lower leverage levels of the rest of the Indian corporate sector. By doing so, the RBI has refused to acknowledge that the real issue for the private corporate sector as a whole is not a balance sheet problem but aggregate demand in the economy. Even if the balance sheet issue is resolved with the banks and with the over-extended large business houses, credit in the economy is unlikely to rise significantly as presently the under-leveraged companies forming the bulk of corporate India are not in need of additional funds. Once policy-makers concede the major issue is of aggregate demand, then the solution is for the government and the central bank to implement expansionary policies such as higher fiscal deficit and lower interest rates. However, this has been anathema to them till now.

Private sector infrastructure investment, which led the boom in the Indian economy, has resulted in huge pains for the banking sector, whose exposure to this sector is a significant Rs 9.14 trillion as on June 24, 2016. Infrastructure loans which grew by 10.5% in FY2015, (down from 41% growth in FY2010) decelerated sharply to 4.4% in FY2016 and a negative 2.1% (year-on-year) for the period ended June 24, 2016. One of the reasons for the recent poor growth in infrastructure loans is the UDAY scheme, which involves a shift in the classification of state electricity distribution loans to state-issued bonds to revive the state utilities. The sheer size of the infrastructure portfolio has resulted in its poor growth, in turn affecting overall bank credit growth. There is an element of truth to the argument that banks have stayed away from infrastructure lending from FY2016 onwards on account of asset quality, as the overall stress (non-performing loans plus ‘restructured’ standard loans) in infrastructure stands at 16.4% in FY2016.

High growth rate in steel loans

In the RBI’s recently released annual report, what is revealing and what the central bank and banking regulator is neither highlighting nor clarifying, is that banks have continued to post higher growth in the high-risk basic metal and metal products (essentially steel) loans. The situation in the metals sector is even worse than in the infrastructure sector, with an alarming stress ratio of 34.4% in FY2016. Bank loans to this highly vulnerable sector stood at Rs 4.195 trillion on June 24, 2016. Yet bank lending to it increased by 6.8% in FY2015, 7.9% in FY2016 and 9.2% (year on year) for the period ended June 24, 2016. Though these growth rates are lower than those for non-food credit in FY2015 and FY2016, they are significantly higher than the overall credit growth to industry, which rose by 5.6%, 2.7% and 0.6% in the same period.

The high loan growth to the basic metals and metal products sector which the RBI’s FSR June 2016acknowledges “accounted for the highest stressed advances ratio as of March 2016” is a grave concern. Transparency demands that the RBI disclose the reason for this high credit growth in this sector at a time when the regulator is supposedly being stringent on banks disclosing poor quality loans. Are banks ‘ever-greening’ (giving additional loans to a defaulter to maintain the asset as standard) their high-risk loans with RBI’s unwritten consent? Have the government and the RBI decided to bail-out the steel sector through the majority-owned government banking sector? Or have the measures undertaken by the government such as increase in import duty for steel products, additional safeguard duty imposed and a minimum import price stipulated resulted in genuine improvement in the sector? Or, for some strange reason, is it that the highly-rated companies (e.g. Tata Steel, Hindalco and Steel Authority of India) are raising additional debt? As basic metals and metal products sector accounts for 6.4% of non-food credit and 15.8% of loans to industry, the RBI as the sentinel of the financial system has to investigate and disclose to the public why there is a relatively higher growth rate in loans to a high-risk sector, especially in the most recent period.

The growth in loans to the metals sector also defies the much touted-explanation that bank lending is balance-sheet constrained and shifting away from stress-ridden sectors. As per the RBI’s latest report on the sectoral deployment of credit as on July 22, 2016, the credit growth even in other high-risk sectors like chemicals (stress ratio 11.8%) and construction (stress ratio 27.1%) is 1.4% and 4% respectively, as compared with the industry credit growth of 0.6%. In FY2017, the asset quality stress on banks and the depressed nature of industrial credit does not seem to deter banks in providing additional funds to stressed sectors like metals, chemicals and construction. The media, analysts and even the RBI have highlighted the high credit growth rates in retail, which is definitely much higher than the overall credit growth, but insufficient attention is being paid to why banks continue to lend relatively more to certain high-risk sectors.

Retail immune to the broader economy?

The RBI also does not seem to be concerned with the high growth taking place in retail loans in the industry as gross non-performing loans in housing (single largest segment in retail loans at 54% as of July 22, 2016) is only 1.3% in FY2016. With corporate credit growth in the doldrums, banks are aggressively expanding their retail portfolio in the hope that it will compensate for the low growth of industrial credit. Retail loan yields for banks in June 2016 vary from 10.5% per annum (pa) for housing to 38.3% pa for unsecured credit cards, as compared with loan yields from industry and trade of 12% pa to 12.2% pa, as per the latest annual report of the RBI.

However, the state of the economy as a whole remains bleak. Industrial activity remains depressed, with the annual Index of Industrial Production unable to cross 2.8% since FY2013 and at only 0.6% for April-June 2016 as compared with 3.3% in the same period last year. Total financial flows to the commercial sector in April-August 2016 are down by an alarming 22% to Rs 2,873 billion from the same period last year.

Just as infrastructure loan growth by banks grew disproportionately in the post-Lehman period as the government, to limit its own fiscal commitment, shifted the onus on banks to finance private sector infrastructure, so too it appears that banks are asymmetrically increasing their retail loans currently to outgrow the poor asset quality of infrastructure and corporate loans. The financing of infrastructure then was justified on the grounds that in an infrastructure-starved country there was a secular demand for power and roads and loans would be serviced through the insatiable appetite for infrastructure. The strategy went awry as demand subsequently collapsed with the slowdown. In the current retail loan boom, the rationale is less clear apart from the argument that home loan defaults are marginal on account of low loan to value (of property) ratios and the severe shortage of housing. The segment of borrowers to whom banks are providing housing and other retail loans apparently already belong to the organised economy and have access to bank finance; and the banks regard them as low risk, but their incomes are directly linked to the economy. A major underlying risk that could surface with the banks current retail loan strategy of pushing loans is that some of the earlier fast-growing sectors, such as the information technology (IT) industry, have cut back on recruitment and shifted to lower paying contract labour. Real estate inventory is piling up in the premium segment and employment is stagnating in industry – in such circumstances, from where are the retail borrowers going to service their loans?

In such a bleak environment, should not the banks and the regulator exercise caution in retail loan growth, or do they believe that the retail sector in India is immune from the broader economy? Retail borrowers earn their income in the real economy and when that is stagnating, a certain percentage of retail borrowers too will face difficulties servicing debt. An early warning sign in bank credit is when any segment grows much faster than the aggregate on unrealistic assumptions of low default rates and secular demand. It is worth recalling that the earlier euphoria regarding infrastructure loans, with the regulator being a mere spectator, has left disastrous consequences for the banking industry.

The government and the RBI need to articulate and co-ordinate their efforts in directing bank credit to stimulate the economy. Their earlier focus on getting banks, especially government-owned banks, to do the heavy lifting of disbursing high-risk infrastructure credit to drive private sector investment in the economy has wound up crippling banks and now the government is being miserly in recapitalisation. The current strategy of rampant retail credit growth and additional credit for high stress sectors like steel, chemicals and construction does not appear to be a part of well thought-out plan for economic revival, but an ad hoc solution to defer existing problems.