The Gurgaon Sessions Court on March 10, 2017 delivered its verdict in the Maruti Suzuki rioting and arson case of July 22, 2012 at the company’s Manesar (Haryana state) factory which claimed the life of its human resources general manager, Awanish Kumar Dev and caused widespread destruction at the facility. The police arrested 148 company workers and the company sacked around 500 of its 1,500 permanent staff at the factory. The court verdict acquitted 117 workers (most of whom had already spent over 3 years in jail) and convicted 31 workers; 13 workers were sentenced to life imprisonment, 4 were given 5 years imprisonment and the remaining 14 were let off with what they had already served.

For Maruti Suzuki, India’s largest automobile company (market share of 46.8% in FY2016), the court verdict may not be the end of the labour issue as the labour union will appeal to the Punjab and Haryana High Court. Furthermore, the Sessions Court verdict will also not resolve the critical labour issues in the automobile industry; the fall in real wages over a lengthy period of time and the high disparity in pay (can be more than double) between two category of staff who do the same work on the shop floor: permanent and contractual (temporary) workers. In reverting back to its emphasis on low-cost contractual labour, the company is taking a calculated risk that with the support of the state it can control its work force and focus exclusively on dominating the market and higher profits. But, labour discontent is simmering in the automobile industry and with the deliberate suppression of trade unions independent of management, the institutional mechanism to resolve disputes has been considerably weakened resulting in explosive violence replacing dialogue which may disrupt the upward linear trajectory of analysts’ earnings forecasts.

The automobile industry in India has been one of the jewels of success in the Indian economy, taking advantage of the increasing domestic and export demand for Indian manufacturers, encouraged by government policies focusing on private transportation and roads instead of the more cost effective public transportation and railways. But while shareholders of automobile companies have been richly rewarded with the phenomenal increase in profits and market capitalization of majors like Maruti Suzuki, factory workers have paid a heavy price. The labour problem at Maruti should not be seen in isolation but as a reflection of the practices adopted by the entire industry to improve profits.

Despite archaic and supposedly rigid labour laws in India, the corporate sector has been able to expand and, more importantly, contract the labour force at will, and to shift the composition of its workforce from primarily permanent to lower cost contractual labour. This has been achieved by curtailing trade union rights, with the support of state governments wanting to promote investment by assuring industry of a compliant labour force.

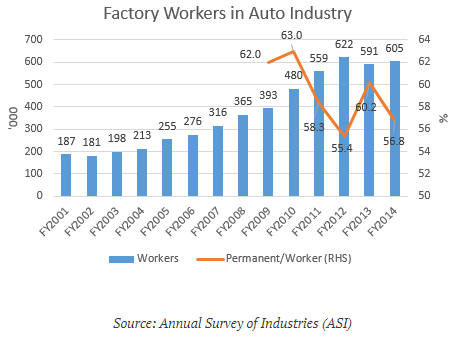

In the automobile industry, as per the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI), since FY2001, the labour force contracted in FY2002 and again in FY2013 and permanent labour ranged from 63% of the workforce in FY2010 to a low of 55.4% in FY2012, despite the much-hyped rigidity in labour laws. The official data may also be under-reporting the non-permanent staff as academics undertaking field research stated,

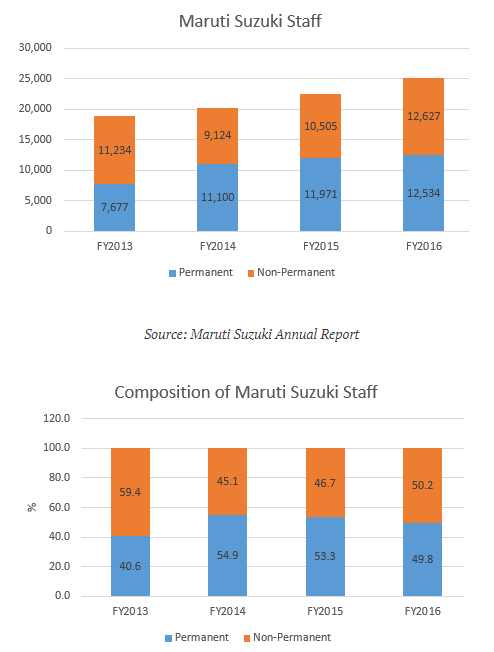

By FY2013, Maruti Suzuki according to its annual report disclosure, was able to successfully transform nearly 60% of its labour to non-permanent (including apprentice and trainees) workers. The automobile sector in India was able to bypass the labour laws with relative ease and it was not a major impediment to labour flexibility.

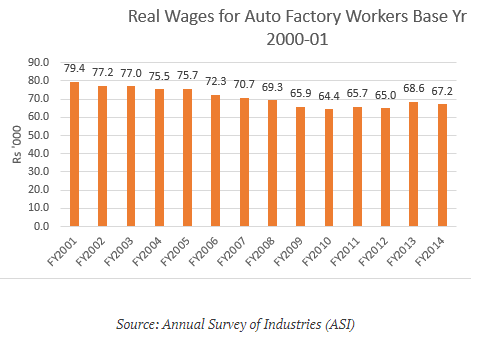

The weakening of automobile workers’ bargaining power as a result of dismantling of trade unions, the state-corporate partnership to effectively bypass labour laws to promote industrialization and higher corporate profits, combined with higher consumer price inflation for industrial workers, resulted in real wages consistently declining for nearly 10 years between FY2001 till FY2010. Thereafter, it partly revived, but even in FY2014 (latest year ASI data is available), the real wage is significantly below FY2001. The working conditions in Maruti’s factories resembled a sweat shop with enormous pressure on the workforce to meet production targets. It is evident that in a period when the automobile industry was doing well, its workers were not.

It is in the backdrop of these developments that the labour unrest in Maruti during FY2011 which finally culminated in the violent incident at its Manesar factory has to be seen.

“In Manesar, contract workers were paid just Rs 7,000 a month ($155) while salaried workers were paid Rs 17,000 a month ($376) for the same work. Salaries at the factory increased by just 5.5% between 2007 and 2011 at a time when the consumer price index for the region went up over 50 percent. Meanwhile, profits for Maruti Suzuki had increased by 2,200 percent over the previous decade.”

Post the violent incident at Manesar and the widespread publicity, Maruti Suzuki publicly assured it would reduce its contract workers. Indeed, in FY2014, the company reduced its non-permanent workers to 45.1% from 59.4%. However, thereafter increased it once again to half of its work force. Interestingly, it was not competitive pressure as the company’s profits continued to grow. The reversal of its strategy indicates that the company is willing to accept the risk of a disgruntled labour force so that it can report higher profits for its shareholders.

Within hours of the Gurgaon Sessions Court verdict, 30,000 workers at Maruti Suzuki plants and supplier factories near Manesar declared a one-hour strike, despite management warnings of an eight-day pay cut. The strike impacted production at Maruti Suzuki assembly plant in Manesar, another assembly plant in Gurgaon, Maruti Suzuki Powertrain, Suzuki Motorcycle India and two auto parts companies indicating the widespread resentment in the area.[1] Although the verdict favoured the company, labour discontent simmers in the vital Manesar-Gurgaon (in Haryana state) industrial belt.

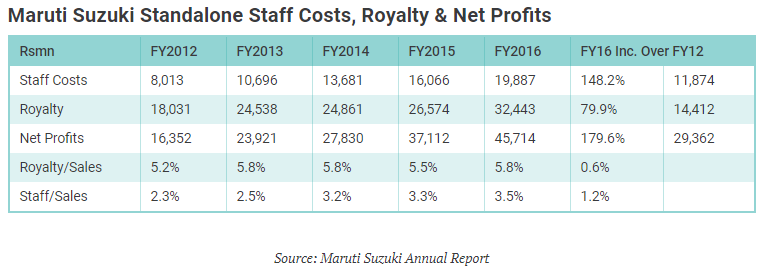

For Maruti Suzuki, the simmering labour discontent appears to be an acceptable risk for its future strategy for higher sales and profits. The fact that the sessions court acquitted 117 workers, most of whom had already spent more than 3 years in jail and indicted 31 workers for the death of one managerial staff indicates the punitive punishment imposed by the state on labour, and management may take a view that this stringent punishment may have coerced its labour force. It is unlikely that management will significantly improve the wages of its entire workforce or increase the proportion of permanent workers, as to do so would not only increase labour costs but also weaken its bargaining power with labour in future negotiations. Moreover, labour costs is the only major cost apart from royalty which is in management’s control, as raw material costs are dependent on extraneous factors as are interest rates.

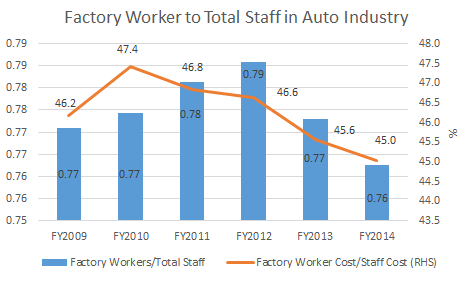

According to ASI data, which segregates labour cost, in the automobile industry in the period FY2009 till FY2014, while the ratio of factory workers to non-factory workers remained constant at 0.8, factory workers costs to total staff cost has not only been less than half but has also been in consistent decline from FY2010 to 45% in FY2014 indicating that non-factory labour, essentially managerial cadre is taking a more generous share of the labour pie. In the last 5 years, Maruti’s net profits have grown at a faster rate than staff costs. Annual accounts to shareholders do not segregate staff costs between factory and non-factory staff costs, and it is possible that the bulk of the increase in Maruti Suzuki’s staff costs may be on account of increase in managerial staff costs. The increase in royalty payments indicates that the company does not wish to curtail this significant outflow which may impact the Japanese parent company’s profits.

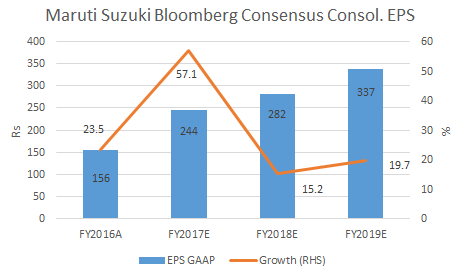

On Bloomberg, 55 analysts track Maruti Suzuki and 82% have a ‘Buy’ rating on the market leader in India but rarely is the factory worker issue highlighted in depth and the risk it poses to the consensus optimistic view on the stock.

If the automobile industry also follows Maruti’s labour strategy of a dual labour force with high differentials in wages for the same work, incorporates the work culture of a sweat shop and discourages trade unions, future conflict between management and labour may be explosive and violent, perhaps even disrupting the linear upward projections of analysts’ earning forecasts.

DISCLOSURE & CERTIFICATION

I, Hemindra Hazari, am a registered Research Analyst with the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Registration No. INH000000594). I have no position in any of the securities referenced in this note. Views expressed in this note accurately reflect my personal opinion about the referenced securities and issuers and/or other subject matter as appropriate. This note does not contain and is not based on any non-public, material information. To the best of my knowledge, the views expressed in this note comply with Indian law as well as applicable law in the country from which it is posted. I have not been commissioned to write this note or hold any specific opinion on the securities referenced therein. This note is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide financial, investment or other professional advice. It should not be construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation for any security