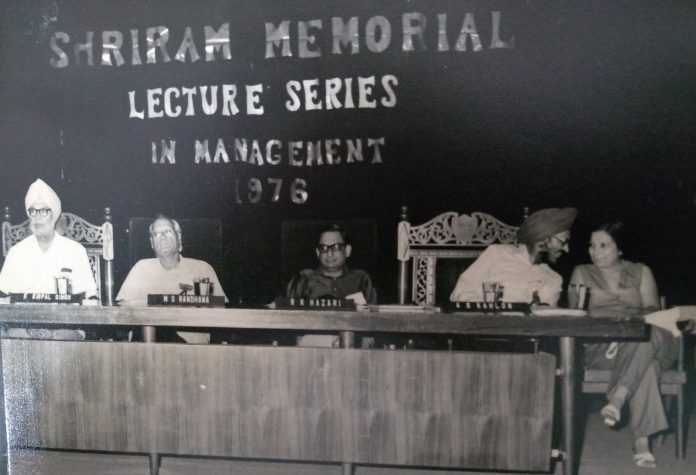

Condensed from Lala Sir Shri Ram Memorial Lectures at the Department of Business Management, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, 1976

Dr. R K Hazari, Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India and Chairman of the Agricultural Refinance and Development Corporation, is a self- proclaimed agnostic. He is proud of having been brought up in the Anglo-French liberal tradition; his personal leanings are influenced by Karl Marx, but he would hate to be confined in any particular mould. The Patrika will serve up in three instalments of what Dr. Hazari has described as his “hotch-potch”, but what is, in effect, an analysis of the country’s economic situation and the remedies it needs. The first article appears on Page 6

Indian Economy what needs to be done-I

The economic trends of the last ten or twelve years do not project a happy picture. Compared with the 1950’s when development nearly took off the ground, there has been a slowing down all along the line, if you leave out 1975-76 which was a rather unusual year. There has been a slowing down of the rate of growth of agricultural production and productivity, of the rate of growth of industrial production, as also the growth of national income and employment. The growth of investment has also been unsatisfactory-Investment is not the only determinant of income trends, but investment is a necessary initial condition for stepping up the growth ‘ of income. What is more, there has not been that kind of upsurge in public investment which also is a necessary condition for sustaining growth. Public investment is normally for such items as electricity, railways, construction, major irrigation dams, roads and so forth There is no ideological conflict about who is going to undertake this kind of investment Notwithstanding our objective of the public sector occupying the commanding heights of the economy’. the trends in the growth of public investment have not been encouraging-

There has been a welcome growth of private investments a large part of it in agriculture. During the last two or three years, there has been a most welcome improvement in the facilities for minor irrigation in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, and the awakening has spread to Rajasthan Bihar, Orissa and Bengal. You would be interested to hear that Bengal is becoming a large wheat producer. The North-East, with its very difficult terrain, has yet to wake up to the possibility and opportunity of development, but this too will come in due course. As you are very well aware, the Green Revolution is now spreading to rice also, and there has been some progress, not wholly satisfactory, in the application of the new technology to coarse grains. As the Green Revolution spreads more particularly to what I call the Ganga Valley, namely, Uttar Pradesh. Madhya Pradesh. Bengal, Orissa. Bihar and the North-East, you will find results that can be even more remarkable and impressive than have, been achieved in Punjab and Haryana.

Some of you might recall, if I may move to industry, that a number of heavy engineering plants were set up in Ranchi and around Calcutta in the late fifties and early sixties- When these plants were being installed, we were repeatedly told by the Minister concerned that, on completion of these plants, we would be abler to produce one steel plant every year. In those days, when we were producing 2 million tonnes of steel per year. if somebody had said that we would be producing 25 to 3O million tonnes of steel by the 1980s, nobody would have laughed at us. Last year when we produced 6 million tonnes of steel, we could not sell all of it and had to build a large stockpile even after effecting sizable exports, which is a measure of the problems that we have got into.

Why did we get into these problems. Till I960, we spent much less on defence than we should have. The proportion of national income spent on defence used to be slightly less than 3 per cent and we allowed our armed forces to be under-equipped, under-trained and under-exercised. When the Chinese danger “became manifest, we started stepping up our defence expenditure till, by 1966, it came to about 6 per cent of the national income. These percentages can be rather deceptive because 1965 and 1908 were rather bad years for national income but the fact remains that, in the sixties, we greatly stepped up the visible proportion of defence expenditure to national income- Though it was brought down slightly later, it has been stabilised in the seventies at a level much higher than in I960, partly because the growth of national income has been less than was expected. We do not know the total amount spent on domestic security because police expenditure is placed under many different heads in the Central and State budgets. Our total expenditure on defence and security has, nevertheless, risen steeply since 1960 and has made a significant dent into the resources available for productive investment. I am not saving that defence and security are dispensable items but that we were, at one extreme in the fifties and have gone to the other extreme since. I am all for defence and security but at the end of it one has to ensure that there is enough left to defend and secure Government expenditure that could have been incurred on river valley projects, construction, expansion of railways, and so on, has been diverted elsewhere. Regardless of its budgetary classification, all defence and security expenditure is, in economic terms, current expenditure which does not add significantly in the long run to the level of saving arm investment in the economy.

Further when we set up heavy engineering plants, the idea apparently was to put up huge machines by the tone. About 11 years back, I remember visiting a heavy engineering factory where there was a highly automatic machine and by its side there was a semi-automatic machine, both for the same purpose. I wanted to know why it had both. I was told that we got the automatic machine because it was the most advanced available with the particular supplier, but that there was not enough work for it so we installed a semi-automatic machine too. In the event, both machines were then nearly idle most of the time. Initially, it was believed that machines would breed machines as a natural phenomenon and designing capabilities were sadly neglected, not realising that the physical capacity to produce machines does not suffice to attract orders unless it is backed with designing capacity. Imports of machinery, therefore, continued, partly because of price, quality and service considerations and partly because of the desire to fulfil investment targets. Meanwhile, in one plant at least, the workers got accustomed to playing cards oil the shop floor and it took three years of painful effort to get them back into the working habit. By the time designing capabilities were built up — as they have been to a large extent — the planning processes had slowed down, till, as of now, there are not enough orders in the pipeline to keep the designers as well as machines busy. Bharat Heavy Electrical needs two years from the receipt of actual orders with the down payment, to really start manufacturing a plant because that is the time required for the designing of the plant, and it takes another three years to deliver the plant. In other words, the current operations of BHEL or any other machine manufacturer depend not so much upon conventional marketing and salesmanship as on a clear perception of the Sixth Plan —which is still far from the conception stage.

Over the years we invested huge amounts in major river valley projects, the benefits of, which were not visible for quite some time. We invested huge amounts in large industrial projects, the benefits for which also did not come for quite a long time. There were similar investments all over the economv which produced a less than expected increase in income and, therefore, did not fully perform the income generating function of Investment. The result has been a shortage of real resources because unless capital is turned over quickly enough, it does not yield the funds out of which fresh investment can take place- You can maintain the pace of fresh investment for some time by asking the Reserve Bank of India to create the money, which is a very profitable proposition for the Reserve Bank, but a very damaging proposition from the country’s viewpoint because it leads to inflation. You can finance one round of development, if you like, with created money- but in the subsequent rounds you must get enough production and profit (or surplus, if you please) in order to be able lo keep on investing and, unless in the country as a whole you keep on investing at a sufficient pace and for a sufficient length of time, you do not create scope for the orders that are required to sustain and expand the level of demand for your industry.

II I may come to more recent events, it is quite true that we had an excellent year in 1975-76 National income has grown by a little more than 6 per cent- comprising as much as 8 per cent growth in agricultural production which is almost an all-time record; and 4 to 5 per cent in industry the pressure on fiscal and monetary policies, namely, a relatively modest deficit in the Government budget impounding on a large amount of additional wages and additional dearness allowances aggregating roughly Rs. 900 crores with the Reserve Bank, further impounding a part of bank deposits, together with the administrative measures taken against smuggling and hoarding, brought down the growth of money supply in 1974-75 to barely 6 per dent (which was one of the lowest rates in the world) and to about 1O per cent in 1975-70. Since the money supply growth in one year tends to influence the price level in the current as well as the next year, given certain output trends, it is not surprising that prices fell between September 1974 and March ‘1976. Two other important factors which played an important role in the price fall were thee large increase in net Foreign aid receipts and in crop production. These have been dealt with at length in various reports of the Reserve Bank.

(To be continued)

Amrita Bazar Patrika May 19, 1977

The second of his three articles on the Indian economy. Dr. R. K. Hazari contends that high tax rates are not essential tor a productive and just social order, they are self-defeating. He argues that in the interest of the people and the elite it is necessary to bring down the present excessively high tax rates and supplement moderate tax rates with compulsory deposits at varying rates of interest— Page 4

I would take the liberty of warning you about not resting on either your past glory in agriculture or the glory of the economic performance of the past year. A large number of factors that accounted for the favourable performance in 1975-76 may not be repeated in future. In fact I am convinced that some of them are not likely to be repeated in the current year. For one thing, the current annual growth of money supply (1976-77) is 8 per cent, ‘in February 1977 it was nearly 18 per cent) which is much larger -than that in the preceding year and certainly much larger than that in the year before, when we took strong anti-inflationary measures. On top of that, it does not appear very likely that the kind of boom that we had in agricultural output last year would be repeated this year. We would be very fortunate indeed if we are able to maintain the crop at last year’s level. If one takes industry, the first half of 1976 was extremely good — an increase of 13 per cent in industrial output as compared with the first half of 1975 but then, the first half of 1975 was a really bad period. The bulk of this 13 per cent growth in the first half of 1976 took place in electricity, coal mining, steel and textiles. It does not appear very likely that this kind of growth would be maintained throughout the year- In fact, textiles are again in trouble, electricity is again running into bottlenecks, additional quantities of coal are not being absorbed readily — there is something like 10 million tonnes of coal lying at the pit-heads — and similarly in steel our production is larger but there is not enough demand and something like more than a million tonnes of steel is lying in stock with the producers, In other words, industrial growth in the second half of the year is unlikely to be as high or fast as it was in the first halt of the year.

The possibilities are of, let us say 8 to 10 per cent growth in industry for the year 1976-77 as a whole and not more then 2 per cent growth in agriculture, giving some thing like 3 per cent growth in national income- These estimates are based on optimistic forecasts about both industry and agriculture. With 2½ per cent growth of population, the increase in per capita income would not be as substantial as it was last year. Viewed against the large growth of money supply, the situation calls for exercise of the maximum care about prices. In February 1977 these estimates stood revised in my opinion to 8 per cent in industry minus 3 per cent in agriculture” yielding a total of less than 2 per cent for national ‘ income and a minus figure for per capita income.

Let me also say that, unlike most past years, Government expenditure the last one year or so has not been responsible for the increase-in prices. In fact, currently. Government (taking Centre and States together) is running a surplus. The increase in money supply is coming from increase in foreign exchange reserves (which in turn is attributable to large increase in exports, decline in imports and large increase in remittances from Indians abroad plus the fact that once your currency is less weak then many others, it becomes more attractive) and increase in bank credit, for food as well as non-food purpose. Ever since the end of World War II, we have been very much concerned about food and foreign exchange, which have been the principal bottlenecks in our development. As of now we have 17 million tonnes of food in stock and we have Rs. 2,000 crores of foreign exchange reserves (excluding gold and Special Drawing Rights) which is equivalent to roughly five months’ imports. In other words, the traditional holes in the frame-work of our economic defence are fairly well plugged. We can take risks which we could not take before- I would still warn, however, that one should not become complacent in matters of food and foreign exchange. In the year 1971 also, we had large food stocks made possible by large output and large involvement of bank credit. There is a similar situation now. It is necessary to keep a large food stock, but there is no particular sense or purpose in keeping such a large stock as a sitting temptation to rats of various species, whether four-legged or two-legged- It is difficult to store such a large stock and to move the large quantities to the centres of consumption- The large accumulation of both food and foreign exchange is, to my mind, essentially an indication of the inadequacy of our development effort.

The foreign exchange should get progressively transformed into steel plants, major river valley projects and a great revival of construction Between them, railways, electricity boards, construction and major irrigation account, directly or indirectly, for more than two-thirds of the engineering orders in the country and similarly, directly or indirectly, they would account for roughly two-thirds of the investment outside agriculture proper- If you have to revive the economy, you will have to undertake A large scale revival, in construction, in electricity, in railways and in major irrigation.

What we need now is the revival of planning. If you produce the Sixth Plan in the middle of the Sixth Plan period. I do not understand how development can tale off the ground just now. If you talk of the current industrial recession, of payment difficulties and inability to pay back loans and so forth, please remember that loans can be paid back only when goods are sold. Goods will sell when there is demand for them, and demand in India is created to a large extent ultimately by plan expenditure mainly on four heads, i.e., construction, railways, electricity and major irrigation works. If you do not have enough of these, you cannot have enough demand for steel and cement and other industrial goods. This planning must be based on non-inflationary financing which requires new methods of control over expenditure and certain attitudes towards some other aspects of civilization like bureaucracy, education and taxation.

I would be prepared to assert any time that some disturbance in the social structure is necessary in order to facilitate social change, but the kind of changes that rapid inflation brings about make rapid and unjust inroads into the standard of living of the majority of the population; the changes are also inimical to the elite because they undermine all the values, institutions, services and mechanisms which motivate and enable the elite to serve the community at large and to justify its existence. A few benefit from inflation if they bought things at yesterday’s prices and sold at today’s or tomorrow’s prices, and thereby made unusual profits, but this is at the expense of the community as a whole, at the expense’ of those who happen to have relatively fixed incomes but whose contribution to social welfare and the maintenance and progress of civilization is disproportionately large. Inflation is particularly inimical to the core of a civilization comprised of its public services, its education, its administration, its system of transport and communications, the working of its municipal and local bodies, the morale, integrity and competence of its public servants, the maintenance of its museums and libraries which inspire pride in the achievements of past generations your own or some other people’s from which you work to bring the glory of the future to birth today.

If there is rapid inflation the public services are hit the hardest because their pricing tends to be sticky, especially in public utilities like railways, electricity and educational services, and the remuneration and status of those who work in them suffer much more than any other part of the community It leads to devaluation of the quality of life which is the duty of the public services to maintain. When you have demoralisation of our public servants, of your educational services, of your so called bureaucrats, then, it is inevitable that the charge of social affairs which lies in the hands of Government (particularly when we do not have a Church or a party to take care of communal life) will tend to be neglected, and cause social demoralization, far beyond economic distortions.

There can never, however, be complete virtue or optimality in any system, one has to be alive to the need for some flexibility. Even while looking or working for a non-inflationary system, one has to allow for a moderate or tolerable degree of inflation. I would say that, in the light of past experience. 2 or 3 per cent annual inflation is something tolerable. Anything more than that is highly detrimental to the best possible allocation of resources, and to social stability and balance in any community or in the world as a whole.

I may now move on to the presumptuous task of suggesting how economic development can be promoted as an investment system with the least inflation simultaneously with the maintenance of certain minimum ethical standards, all for an objective quality of life, consistent with mass market, mass consumption, mass production, mass communication, where one is concerned with the requirements of the whole, as well as with the promotion of social excellence, to which an elite must be dedicated. The objectives that I am setting might appear somewhat romantic but’ my proposals are quite mundane.

First, the level of investment has to be increased and, let me repeat, it has to be financed to the maximum extent possible from resources generated internally from each activity, sector and the economy generally, so that the level of inflation is kept within tolerable limits. In the twentieth century, it has somehow come to be believed that high tax rates are essential for a productive and just social Order. I am convinced that high tax rates are self-defeating whether as a device for resource mobilization or for reduction of inequality. I am greatly impressed, on the other hand, by a proposal made by one of our oldest and seasoned bankers, Dr. T. Madhava Pai, that taxes could be replaced by a system of compulsory deposits without interest. I would not go so far as to replace all taxes by compulsory interest-free deposits of various maturities but I do believe that it is possible and necessary in the interest of the people as well as the elite to bring down the present excessively high tax rates, and supplement moderate tax rates with compulsory deposits at varying rates of interest arranged in progressive slabs descending from attractive or normal rates to zero. It can be demonstrated that if you pay no interest at all on borrowings or progressively lower rates of interest on increasing amounts of deposits made by high income earners, then, the compounded effect over a period of time is the same as that of a progressive marginal tax rate- Thereby, you still maintain the egalitarian principle; you also obtain the resources essential for growth without making the tax-payers feel that it is their fundamental family and business dutv to avoid or evade taxes.

Second, it is necessary to re-interpret what is meant by priorities. Even such high priority item as food, power, steel or fertilizer do not have infinite priority. Nothing in this world can have an infinite value attached to it; values have to be finite and relative. It follows that rather than distinguish between what are called priority sectors and non-priority sectors or priority-commodities and non-prioritv commodities, one should seek balance between the sectors or commodities or resource uses at various levels of relative combinations If, for instance, electricity has high priority, that does not mean that all the resources available in the economy must be devoted to investment in electricity. If one does that, there will be no investment in the uses of electricity and all the investment made in electricity would go waste. Similarly, with investment in fertilizer, there is a point beyond which the utility of fertilizer alone keeps on declining; we have to invest much more in water along with it; we have to invest in other improvement in the techniques of cultivation, and so forth.

(To Be Concluded)

Amrita Bazar Patrika May 20, 1977

In the third and last of his articles on the Indian economy. Dr. R. K. Hazari pleads for investment in the elite and for the elite. He says it is essential to invest specifically, consciously, organizationally in the creation and development of an elite, and elite leadership is best organised on a plural rather than a monolithic basis Page 4

Our actual approach to priorities has been: based upon what can almost be described as a caste system, in which a sector or commodity is born into a priority rather than inter-related with others at various finite values at different points of time. In defence logistics I understand, the prime importance is not on weapons alone but certain combinations of men, weapons, ammunition, supplier, transport and time- While the process of planned development is often compared with war rather inappropriately in my opinion this basic tenet of logistics has yet to be incorporated in our thinking and action on planning.

One further elaboration of the concept of priority is required. The latest difficulty encountered in implementing any programme on the basis of priorities indicated by higher authorities is that they keep on mentioning priorities and high priorities but they never spell out the posteriorities or for that matter, the fall-back positions in the event of setbacks. It is relatively easy to say what is important but very painful to specify what can be cut down or cut out. In actual implementation, however, the perception and observance of posteriorities is crucial—and that is where, one needs both self-confidence as well as the confidence of superiors and subordinates. Society must have a value system which recognises that priorities imply posteriorities and that benefits involve costs. It is an accepted dictum that an army commander is entitled to shed the blood of his enemy as well as of his own troops. There has never been a battle in which blood has not been shed. In peaceful pursuits, unfortunately, and in the implementation of policies, we seldom recognize that development or anti-inflationary measures also involve casualties in different forms. Further, the framing of policies or announcements normally takes place in a mood of optimism and little attention is devoted to anticipation of difficulties, bottlenecks and possible set-back. When these difficulties are encountered, there is a tendency to hand out blame to others and take refuge in defensive departmentalism which is another name for avoiding a systems approach.

I should now attempt to indicate the areas where investment has to be promoted. There are three broad areas in which there is a need to promote investment.

One is exploitation of natural resources, mainly in agriculture, flood control, soil conservation, and irrigation and mining. If you go to eastern UP, Bihar, Orissa, Bengal and the North-East, you will realise that one of the principal reasons why they have been left behind in the development process is that thev are often washed away, in some places, twice a year. Even if they had the spirit that the Punjabis are reputed to have I doubt, if they would have been able to stand opto this type of destruction year after year for decades. What is the use of investing in the land if your crops are going to be washed away repeatedly? One of the reasons why I pleaded earlier for the revival of investment in major irrigation projects is that minor irrigation—in which I have a large business interest is not something that can contribute to flood control. It is only major irrigation systems and the control of soil erosion (that should be an integral part of them) which can help in controlling floods. One other technique of dealing with the problem, with which you are more directly involved, is the evolution of crops and seeds which give their yields before or after normal flood seasons. Conventional flood control, we all know is terribly expensive, it takes a long time to yield results and even then, its long term utility is not always beyond doubt, thanks to silting up of dams and river beds and frequent lack of attention to proper water management and drainage. Increasingly we must resort to much more of rabi cultivation in the areas which get their floods during the kharif season. This change is already taking place to some extent. The ‘rabi’ crop that is coming up in Bengal is an eye-opener. I am sure that, in Orissa and Bihar also, where minor irrigation is picking up significantly, the possibilities would open up for having crops which can be grown before or after floods, thereby protecting the income and savings of the farming community.

About mining, it is true that coal is having a lean domestic market just now, But our coal reserves are one of our greatest assets. Though its ash content is high, we can easily aim at export of at least 5 to 10 million tonnes of coal every year. The production potential is already there but handling equipment in the ports is a severe bottleneck: our port handling capacity for export of coal at present is only about half a million tonnes. We must exploit the immense market for coal outside the country, particularly now that the reopening of the Suez has restored some of our freight advantage. The price of our coal is about three times higher than what it was before the coal mines were nationalized but it is still less than half of the international price.

You might be wondering why I have made no reference to investment in petroleum. Such investment is of course necessary and desirable—up to a point—but, rather than join the general chorus on this issue I would like to emphasise that petroleum is less important than water. Petroleum can be imported at a price while water has to be harnessed and utilised at home for the benefit of millions of people—for domestic use, for agricultural productivity and employment, and for industrial purposes. Water makes a larger contribution to human welfare and employment than any other natural resource. The main solution to the problem of unemployment is agriculture, in fact, lies in increasing the availability of water on a scientific basis for enlarging the demand for labour.

The second field of investment is the transformation of matter through industry and services. I have already referred to electricity, construction and railway. To these, I would add roads, communications and municipal facilities. All of us know that roads are useful, but when Government imposed a ban on fresh construction activity in November 1973 and thereby deprived several lakhs of persons belonging to what are described as the weaker sections of their present or potential jobs there was hardly any protest. Contrast this with the outcry you witness as soon as a mismanaged or unmanaged industrial unit is threatened with closure and a few thousand industrial workers are in danger of losing their jobs- Since the lifting of the ban last year, there is some revival of construction activity but, again, in the practical absence of forward planning, it is far from a boom phase. Roads are a great necessity., particularly, in the central, eastern and north-eastern regions.

Communication is a sadly misunderstood term. Somehow when one talks of communication, some people have visions of radio and telephones and aerodromes being luxuries. For one thing, the telecommunication industry is highly labour-intensive. For another, quick communication is essential for conveying of ideas, for enlarging the size of the market, as also for improving the efficiency of information and control systems required for administration and business. Since direction and decision-making are bound to be more or less centralized, diffusion of economic activity can be promoted only if the communication system is good and efficient. The construction of airstrips is not a luxury where the terrain is difficult or the distances are long. If you want diffusion of economic activity, if you want the elite to travel more and be in close touch with the people, and to make quicker and more sound decisions, it is imperative that executives should be able to travel and communicate quickly between their headquarters and present or potential units of production. Just because some of these facilities are at times misused for private or partisan purposes is not a sufficient argument for not developing them consciously as an integral part of a comprehensive investment system.

Our municipal facilities, whether in towns or villages are sadly neglected and are, in general, characterised by lack of local initiative, local consciousness and local management. It is quite easy to create municipal local bodies and even spend funds in their behalf. What I am pleading for is not just larger investment in water supply sewage, town planning, roads, libraries etc-—all of which are important—but for greater positive local consciousness of the need for such facilities and their efficient management. Our local bodies are known for their inaction and petty intrigue, rather than their performance. Giving them more money or temporary administrators is really no solution. We need an organized effort to improve municipal bureaucracies as well as public consciousness about what they should expect from their local bodies, rather than from a relatively distant and top-heavy government. The overhead costs of infrastructure like power, roads, transport education and cultural activities could be greatly reduced if they were managed locally in compact organisations rather than left to leviathans spread over a whole State or country.

Third, and to my mind, most important, is the investment in manpower and human, resources, more specifically in training and in bureaucracies of different shades. Trainers and bureaucrats are supposed to enjoy much prestige, but actually they are much devalued. When many years ago I announced to my friends that I intended to become a teacher, they doubted my sanity while recognizing that education was a noble profession. Similarly, while bureaucrats, whether in administration, business or technical occupations, enjoy a certain degree of authority, the bureaucrat has become a much-maligned animal, as the Bania was earlier. The Bania is a much criticized and much condemned person because he is useful, he is convenient, and he is economical; familiarity with him has bred contempt. The bureaucrats do not have all these qualities but since they, too are all over the place now. and do perform some useful and essential functions, they have qualified for public contempt.

Public acclaim and respect are a necessary but not sufficient condition for successful investment in human resources. In a system, view of man-power training, it has to be recognized, first, that in agriculture and traditional crafts, most of the skills are acquired by domestic training and observation but increasingly, one needs public organizations (e-g- . for extension, marketing and credit to improve productivity, employment and income. In this context even more than elsewhere, one has to ensure that the organizations are low-cost, high benefit set-ups. In public sector organizations of this sort where the normal business criteria of performance do not apply, costs can easily get out of hand and become a national burden. Second, the moment one gets away from general purpose education, the objectives and mechanisms of training have to be spelt out and understood clearly, so as to maximize the return from investment in human resources. Employment needs and prospects have to be projected consistent with the pace, phasing and pattern of development — recognizing, at the same time, that society and the institutional framework are not wholly amenable to metallurgical treatment. Third, the concepts of maintenance, depreciation, replacement and plough-back— and even inflation accounting are as relevant in respect of manpower as they are in material or financial investment, except that the concepts are somewhat amorphous, and the results are intangible but certainly not invisible.

Investment has to take place in the people and for the people also in the elite and for the elite. In the armed forces and in well-organized, well-managed enterprises, there is great emphasis upon orga-nizational loyalty and fellow feeling; simultaneously, the training or learning effort is attuned towards specific purposes and structured, suitably for various levels of hierarchy corresponding to their functions, authority and responsibility. I have yet to hear of an army which has contemplated identical expectations of and training programmes for NCO’s, captains, colonels and generals. For war and business we are-willing to be organized consciously, but when it comes to the management of society and civilization, we have many excuses. I am as I have stressed earlier, a firm believer in socializing the benefits of technology, and in mass market, mass consumption, mass production and mass, communication; for achieving all these, it is essential to invest specifically, consciously, organisationally, in the creation and development of an elite.

Leadership as represented by an elite is best organized on a plural rather than a monolithic oasis. Why did conquerors in ancient times, restore their kingdoms to defeated kings and ask them to continue as subordinate rulers? The rationale lay in not humiliating the opponents too far> but putting their talents and organisation to use. So that they would be loyal and faithful allies not driving them into a corner from where, they would rebel at the first opportunity. That was subject to effective deterrence and discipline—a cheaper system of administration than imposing the direct rule of the conqueror. In our society, too, we should seek to transplant and hybridise this technique into the power structure, so that we have hierarchies of multiple leadership at different levels and in different areas. Otherwise, you get a system (or non-system) in which it large number of subservient officials— whether political or administrative; wait to Carry out orders and instructions from above; they have neither initiative nor are they expected to exercise any initiative-One must have centralized direction in any system but there must be plenty of room for decentralized initiative and adaptation. Let us not repeat the performance of the defenders of the temple of Somnath, who waited for divine intervention or the auspicious occasion to put up a fight against the enemy and therefore, the temple was sacked by Mahmud Ghaznavi without a battle. In that historic event, initiative was centralized in God or His agents on earth- We should learn to do better. (Concluded)