The unseemly public jostling between India’s central bank and the government of India casts a poor light on both institutions. Adhering to unrealistic fiscal deficit constraints has compelled the government to plunder public institutions such as the Life Insurance Corporation of India, ONGC and now the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to garner any available resource by any means. In the present context, the government was apparently eyeing the surplus of the central bank to meet its fiscal deficit target. Although a senior official of the government has since clarified that the government has no intention to transfer the surplus to the government, global investors need to be aware of the limits to the independence and autonomy granted by law to India’s central bank, and the implications of such a transfer of surplus to the government.

Many commentators have remarked on the erosion of RBI’s independence and autonomy in the apparent demand (subsequently denied by the government) for transferring the RBI surplus to the government so as to meet targets for fiscal deficit reduction.

The public and global investors should be made aware that the RBI’s autonomy is at the discretion of the Indian government, and as per the law, India’s central bank is subordinate to the government. In a lecture series on ‘RBI and its Autonomy’ organised by the Forum of Free Enterprise on March 6, 2017, Rajendra Chitale,a prominent chartered accountant stated,

“While debating autonomy and independence of RBI, it would be instructive to understand as to whether the independence under discussion is indeed de jure, that is, enshrined in the law, or it is de facto, and flows from past practice and convention. Significantly, the independence and autonomy of RBI that we speak of is entirely de facto and not de jure.”

There are two critical sections in the RBI Act, 1934 which demonstrate the subordinate nature of the relationship between the RBI and the government. As per

“Section 7(1) The Central Government may from time to time give such directions to the Bank as it may, after consultation with the Governor of the Bank, consider necessary in the public interest.”

In the recent debate in the media, reports have cited the fact that the government threatened to use this section to compel the RBI take certain actions. It is pertinent to note that “consultation” with the RBI Governor does not mean consent, and if the government has to use this hitherto never used section, it has to argue after consulting with the governor, that it is in the public interest to do so.

Section 30 of the RBI Act, 1934, dealing with powers of the Government to supersede the RBI, states,

“If in the opinion of the Central Government the Bank fails to carry out any of the obligations imposed on it by or under this Act the Central Government may, by notification in the Gazette of India, declare the Central Board to be superseded, and thereafter the general superintendence and direction of the affairs of the Bank shall be entrusted to such agency as the Central Government may determine, and such agency may exercise the powers and do all acts and things which may be exercised or done by the Central Board under this Act.”

These two sections, although never utilised, lucidly highlight that the citizens of India did not want the country’s central bank to be independent and or totally autonomous of the central government. The RBI functions within the autonomy provided by the government, which the latter can increase or reduce at its discretion. If, however, the central government were to utilise either of these sections, the responsibilities for these actions would be on the government and not on the central bank.

As the RBI Governor and deputy governors are not elected officials, they do not enjoy a public mandate, which rests with the democratically elected government. Capital market commentators, especially those who represent the interests of global capital, would do well to remember that in the case of the RBI, legally the central bank is subordinate and finally subservient to the government.

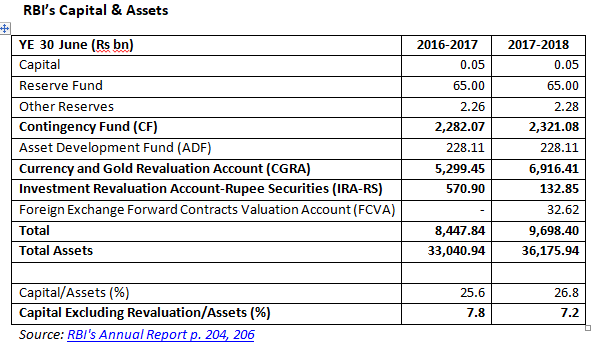

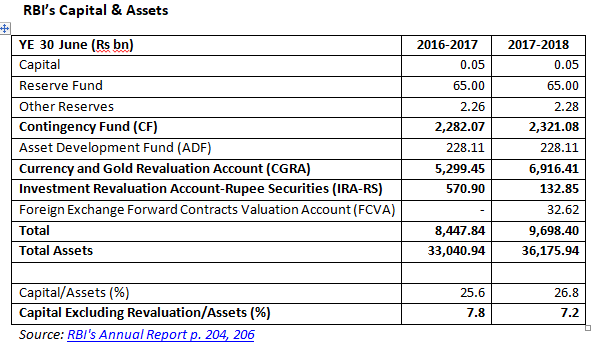

As per media reports, the government wanted the RBI to part with its reserves, as it believes the central bank to be over-capitalised. The media reported that the government wanted the RBI to give up an amount of Rs 3.6 trillion to beef up its fiscal deficit. Indeed, the government had been eyeing RBI’s surplus for some years. In The Economic Survey 2015-2016, the then Chief Economic Advisor (CEA) to the government, Arvind Subramanian, had argued that the RBI, with an equity to assets ratio of 32%, was over-capitalised as compared with the United States Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, whose ratios were less than 2%. The Survey said,

“If the RBI were to move even to the median of the sample (16 per cent), this would free up a substantial amount of capital to be deployed for recapitalizing the PSBs [public sector banks].” p. 20

In the following year, The Economic Survey 2016-17 even specified the likely amount that could be transferred to the government,

“Assuming that the RBI returns Rs 4 lakh crores [Rs 4 trillion] to the government…” p. 99

Hence, in the public domain, there is an estimate by the government’s CEA of the amount that the government was considering to transfer from the central bank, and the estimate of Rs 3.6 trillion in the media is therefore not baseless.

There are two main problems with the CEA’s analysis, as with that of other economists who have argued for the significant return of capital from the RBI to the government. A large amount of RBI’s capital is unrealised gains from its holdings of foreign exchange assets, gold and government securities.

Around 70% of RBI’s capital is unrealised capital gains, which fluctuates with the valuation of the underlying asset, and can be realised only by selling the concerned assets. If the RBI were to realise a part of those gains, it would have to sell a considerable component of its foreign exchange assets. The second problem is, as V.K. Sharma, a former Executive Director, RBI argued, that selling a considerable component of the foreign currency assets to realise part of the unrealised gains will lead to a disruption in markets, collapse in asset prices and a contraction in reserve money which will have disastrous impact on the economy. A central bank’s balance sheet is unique, as selling an asset does not result in cash, as in a normal balance sheet, but in a contraction in money supply – similar to conducting open market operations to control money supply in the economy. Given the high component of unrealised gains in RBI’s capital it is not practical for the RBI to sell the assets to realise the assets.

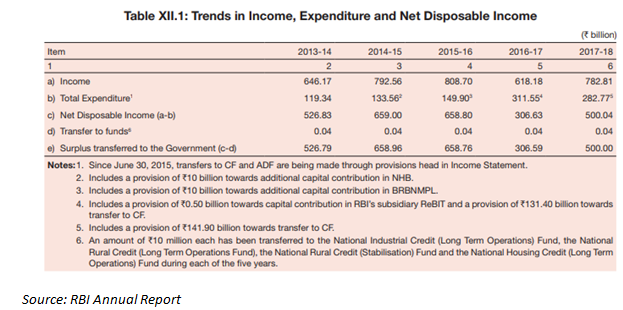

The only capital which the RBI can repatriate to the government is its contingency fund of Rs 2.3 trillion. But if the RBI were to transfer a significant component of it to the government, its own capital will consist of only unrealised capital gains, which may not be healthy for a central bank. For the last 5 years RBI has been transferring nearly its entire disposable income to the government via dividend, and hence its contingency fund is the only fund into which it can dip to provide the government with more funds.

To soothe the media furore the issue was creating, S.C. Garg, Secretary Department of Economic Affairs on November 8, 2018 tweeted,

“Lot of misinformed speculation is going around in media. Government’s fiscal math is completely on track. There is no proposal to ask RBI to transfer 3.6 or 1 lakh crore [3.6 or 1 trillion], as speculated. Only proposal under discussion is to fix appropriate economic capital framework of RBI.”

It is apparent that the government is backing down, or that it was using the threat of utilising Section 7(1) of the RBI Act, 1934 as a negotiating tool to pressurise the RBI to part with some of its capital to the government at a time when there is pressure on the fiscal deficit and national elections are to be held in 2019.

The RBI’s next board meeting is scheduled on November 19, in which the issue of transfer of capital is expected to be taken up. There was some speculation that the RBI governor, Urjit Patel would resign at that meeting: The earlier board meeting on October 23 was reported as being contentious, and led to the sharp tone of RBI deputy governor’s Viral Acharya’s speech on October 26, which in turn sparked the media debate.

On the issue of the ‘surplus’ transfer of capital from RBI to the government, which appears to be impractical, with negative consequences for the economy and the central bank’s balance sheet, the fact remains that if the government continues to insist on it, the central bank has to acquiesce, as the RBI by law is subordinate to a democratically-elected government with a popular mandate.

DISCLOSURE & CERTIFICATION

I, Hemindra Hazari, am a registered Research Analyst with the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Registration No. INH000000594) I have no position in any of the securities referenced in this Insight. Views expressed in this Insight accurately reflect my personal opinion about the referenced securities and issuers and/or other subject matter as appropriate. This Insight does not contain and is not based on any non-public, material information. To the best of my knowledge, the views expressed in this Insight comply with Indian law as well as applicable law in the country from which it is posted. I have not been commissioned to write this Insight or hold any specific opinion on the securities referenced therein. This Insight is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide financial, investment or other professional advice. It should not be construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation for any security.