The RBI’s deputy governor resigned six months before end of tenure following other such goodbyes, indicating a troubled equation with the government

BY SALIL PANCHAL, Forbes India Staff3 min readPUBLISHED: Jun 28, 2019

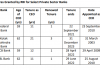

Image: Francis Mascarenhas/REUTERS

The premature exit of the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) deputy governor, Dr Viral V. Acharya, six months prior to the end of his tenure once again raises the concern over the inability of policy makers to work with government officials.Acharya’s exit is not a stray case. Before him, Arvind Panagariya of Niti Aayog, the Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian, former RBI Governor Urjit Patel and his predecessor Raghuram Rajan have all decided to end their tenures prior to their completion.“There is clearly a pattern [to these exits]. Those working from outside of the Indian government find it difficult to work [with the government],” says Hemindra Hazari, an independent banking analyst who writes for Singapore-based research platform Smartkarma.Acharya is the C.V. Starr Professor of Economics in the Department of Finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business (NYU-Stern) and has decided to return to the United States, where he teaches, to be with his family. Acharya had joined the RBI as deputy governor in January 23, 2017, but quit six months before his tenure was to end.In October 2018, Acharya surprised all by calling for the need for autonomy for a central bank from a government. He said, at a public forum, that governments that do not respect central bank independence will sooner or later incur the wrath of financial markets, ignite economic fire, and come to rue the day they undermined an important regulatory institution.“While a lot of what Acharya spoke about in that October speech might have an element of truth, I have little sympathy for him. The RBI, as a central bank, is subservient to the government. He should have resigned earlier [if he was peeved]…. You can’t be like an independent commentator in position of office and make statements which are destabilising,” Hazari told Forbes India.The bigger problem here is that Acharya—like Rajan, Panagariya and Subramanian—were never seen by the government to be part of the Indian system. Acharya was parachuted into the RBI. And then, like others, they have departed without really citing the exact reasons for their exits.Dr Ashima Goyal, well-known economist and member of the PM’s Economic Advisory Committee, says, “Acharya has gone back for personal reasons. Experts who come from teaching jobs have their own calendars, which do not necessarily match the terms of their contracts. Their contributions, even if for a limited time, have their utility. But no one is essential.”Goyal feels all exits will not impact the institutions, though Hazari disagrees.“Career bureaucrats will not exit but experts on short-term assignments will. You need the right mix of the two,” Goyal told Forbes India.Institutions will always be larger than the individual. The problem in the Indian system of policy making is that the financial and capital markets have often put pressure on decisions of the RBI’s monetary policy committee.Sonal Verma and Aurodeep Nandi from Nomura have, in a recent note to clients, said that Acharya’s departure is not a complete surprise, as frictions between him and the government on issues related to central bank independence had come to the fore.With Acharya’s exit, the RBI is likely to be incrementally more dovish, considering that Acharya was considered hawkish in matters of policy decisions.

- RBI cuts repo rate by 25 basis points to 6%

- SC quashes RBI bad loans note; central bank position “undermined”, say analysts

Nomura analysts forecast another 25 basis point rate cut in August (resulting in a cumulative 100bp of cuts in 2019). The focus will now shift towards implementing policy changes through the Union Budget.However, it does not take away the fact that the government has bigger problems to deal with, which go beyond building highways, roads and strengthening social reform policies. In this second term, Narendra Modi needs to build trust, which is in deficit both within and outside of the government.