The central bank’s decision to not spell out a rationale does little in terms of adding to the ownership debate.

Hemindra Hazari BANKING 12 HOURS AGO

It was surely one of the more odd episodes in the history of banking regulation. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recently concluded a ‘settlement’ with Kotak Mahindra Bank, which had dragged the regulator to court. The settlement was more or less a win for the bank’s promoter, Uday Kotak and his demands.

Given the RBI’s long history of attempting to compel Uday Kotak to reduce his promoter stake in the bank, it would have been odd if the central bank had changed its policy to accommodate him.

What happened was perhaps worse as the central bank ultimately decided this issue was an exceptional case, thereby undermining its credibility as a banking regulator. It did not even attempt to justify this specially carved-out one-man exception; indeed it maintained a cryptic silence.

The obvious needs re-stating: a country’s banking regulator must carry authority with the banks. It is for the regulator to decide policy and issue regulations from time to time, according to its assessment of the situation. It is not for the banks to choose which regulations to follow, as if from a restaurant menu.

The origins of the promoter shareholding issue can be traced to the RBI approval to Kotak Mahindra Finance Ltd (KMFL), a non-bank finance company, to convert itself into a commercial bank in February 2003. As per the RBI’s January 3, 2001 guidelines for the entry of private sector banks, the promoter had to maintain a minimum of 40% in the paid-up capital of the bank for a lock-in period of 5 years from the date of getting the license from the RBI.

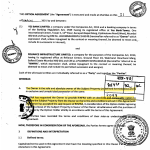

Pertinently, on February 7, 2002, when the RBI gave an in-principle approval to KMFL to convert itself into a bank, conditions 17 and 18 in the annexure to the approval letter specifically stated:

17. As regards the interpretation of the clauses/provisions of the terms and conditions of the ‘in-principle’ approval the decision of the RBI shall be final

18. RBI may impose additional conditions that it deem appropriate…” (p. 5 RBI reply to Kotak Mahindra Bank writ petition dated February 8, 2019)

On June 7, 2002, the RBI revised the minimum promoter holding to 49% from 40% to provide a “level playing field”, as the RBI in February 2002 had approved 49% foreign direct investment in private sector banks.

However, the mismanagement at the erstwhile private sector Global Trust Bank, which led to it being placed under a moratorium in July 2004 and subsequently merged with the majority government-owned Oriental Bank of Commerce, compelled the RBI to change its view regarding bank ownership. It now decided to reduce the influence of private sector bank promoters. In RBI’s February 28, 2005 guideline it emphasised diversified ownership, with any single entity or group of related entities holding a maximum of 10%; higher levels required RBI approval.

Three years later, on February 7, 2008, when the KMB promoters were holding in excess of 49%, the RBI instructed KMB to draw up a plan to reduce the promoter stake to 10%. KMB had originally assured the RBI that the 49% promoter holding would be achieved by June 2007; in fact, it finally was achieved by October 31, 2010, more than three years past the deadline, without any form of censure. Thereafter, till February 2013, the bank delayed bringing down the promoters’ stake to 10% by March 31, 2016.

On February 22, 2013, the RBI issued the revised guidelines for licensing of new private banks, wherein the maximum promoter shareholding was capped at 15% “within 12 years from the date of commencement of business of the bank.” For KMB, the RBI’s guideline meant that, by February 2015, the promoters’ shareholding should have been 15%. But here again correspondence between the regulator and KMB reveals both a prolonged delay by KMB to reduce the promoters’ stake, and the absence of any regulatory action against KMB for not complying with the regulatory norms.

Also read: Why the RBI-Kotak Spat Deserves Far More Attention Than It’s Getting

Finally, on January 30, 2017, KMB agreed to reducing the promoters’ stake in 3 stages: to 30% by June 30, 2017, 20% by December 31, 2018 and finally 15% by March 31, 2020. It also agreed to provide the RBI with its proposed action plan on how it planned to achieve the reduction.

Despite the RBI regularly reminding KMB to share its plan to reduce promoter stake to 20% by December 31, 2018, the bank declined to comply. Finally the bank cocked a snook at the RBI, and issued preference capital, which it argued qualified as “paid-up capital” to bring down the promoters’ stake. But preference capital is merely debt, and in no way fulfils the terms of the regulation. The RBI refused to accept KMB’s interpretation to bring down the promoter stake.

At this stage KMB took the extraordinary step of contesting the regulator’s decision by filing a writ petition in the Bombay High Court.

In KMB’s writ petition and the RBI’s reply, harsh language was used by both parties. KMB alleged that the RBI’s action was “without jurisdiction, wholly illegal, ultra vires the BR [Banking Regulation] Act [1949], manifestly unreasonable, arbitrary, unfair, without the authority of law, and unconstitutional…” The RBI for its part accused KMB of “wilful non-disclosure” of information sought by the regulator, “malafide intent”, “suppressio veri and suggestio falsi [suppression of truth is the suggestion of falsehood]” and of “taking the regulator for a ride”. That the regulator had vigorously challenged KMB’s writ petition and used strong language such as “wilful non-disclosure” (which according to Section 46(1) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 is treated as a criminal offence) indicates the seriousness with which the regulator viewed KMB’s act of defiance.

It is therefore odd that, on January 29, 2020, nearly a year after filing its reply to KMB’s writ petition, the RBI more or less capitulated to KMB’s demands. As per RBI’s final approval with KMB dated February 18, 2020, the promoters’ shareholding will be reduced to 26% of paid-up voting equity capital (PUVSEC) by not later than August 17, 2020 from the existing 30%. Most importantly, no time line has been specified for the promoters’ stake to be reduced to 15%. Instead, the promoters’ voting rights will be capped at 26% of PUVSEC until March 31, 2020, and capped at 15% of PUVSEC from April 1, 2020. Interestingly, in RBI’s final approval, there is no clarity on the status of the preference capital issue and whether it qualifies as paid-up capital – the question which was the subject of the dispute between the RBI and KMB.

There is no guarantee that KMB will abide by this “final approval”, if the history of nearly two decades of correspondence between the RBI and KMB on the issue of reduction of promoters’ stake is any guide. It is a tale of repeated non-compliance by KMB to such deadlines, even after the bank nominally agreed to comply with the RBI’s instructions.

In contrast, the RBI took stringent action against Bandhan Bank in September 2018; when the bank did not reduce the founders’ stake, the RBI restricted its business by barring the opening of new branches.

Also read: Kotak-RBI Tussle Also Has Consequences for Control of the Overarching Group

The RBI has not issued any press release or notification explaining the rationale for its drastic change of stance on the KMB’s promoters stake and why it has carved out an exception for promoter Uday Kotak. As per RBI’s February 22, 2013 guidelines which were applicable to all private sector banks, KMB promoters should have reduced their stake to 15% by March 31, 2015. By the RBI’s failure to enforce the FY2015 deadline, by its allowing Uday Kotak to dictate his own timetable, and on account of the secular rise KMB’s share price, the banking regulator has in effect gifted the KMB promoters (essentially Uday Kotak) a staggering gain estimated at Rs 233 bn (US$ 3.3 bn).

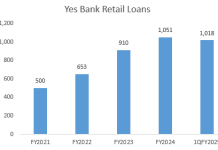

In KMB’s case, the promoter is not an institution which has diversified ownership, but where a single individual is the dominant promoter. Out of the total promoter holding in KMB of 29.96%, Uday Kotak holds 29.7% (as an individual and beneficial owner of a trust) shareholding as on December 31, 2019. Take the case of comparable prominent private sector banks where promoters are individuals: at Yes Bank, which was given its license at around the same time as KMB, the promoters’ holding as on December 31, 2019 was 8.33%; while for IndusInd Bank (established in 1994), the promoters’ holding is 14.68%. In both cases it is below 15%. That the RBI has made an exception to its policy of reducing promoter ownership and influence in private sector banks for just one case is a sorry commentary on the state of banking regulation.

In banking, on account of the high leverage, the holding of liquid unsecured public deposits which are invested in longer maturity illiquid loans, and the critical role played by banks in the payments system and in the economy, it is considered prudent policy to separate ownership (which should be diversified) from management. In KMB, the promoter ownership is concentrated in the hands of a single individual who is also the CEO.

That a private sector individual banker can successfully persuade the RBI to tailor make a special exception for him raises a significant concern. The concern is magnified by the lack of transparency by the regulator in providing this special dispensation. That a single individual can exert so much influence in the strategic banking and financial sector should be an issue of debate, especially as KMB is the holding company for the group’s life insurance, asset management and capital markets businesses.

Hemindra Hazari is an independent writer.