Jay Kotak’s appointment comes with questions for the private banking sector, which has mostly eschewed the dynastic tendencies of old-school India Inc companies.

Jay Kotak (standing) and Manish Agarwal of the Kotak Mahindra Bank’s 811 initiative. Photo: YouTube screengrabSupport Us

Listen to this article:

On May 26, 2022, a proud father hosted his son’s debutante ball. Uday Kotak, though, is no ordinary father. As the founder-CEO of Kotak Mahindra Bank, he is Asia’s richest banker, and the event was to present his 32-year old son, Jay Kotak, as the co-business head of the bank’s 811 digital initiative.

At the function, which cited the theme from “horses to automobiles” to highlight the bank’s path-breaking digital venture, Uday Kotak introduced Jay Kotak. He said that his son had joined the consumer division three years ago, and had been working as an executive assistant to Shanti Ekambaram (president of consumer banking and newly appointed executive director on the board).

In January 2021, Ekambaram selected Jay as co-head of the 811 initiative. Manish Agarwal, a 47-year-old executive with 17 years’ banking experience, has been heading and driving the 811 incubator since March 2017.

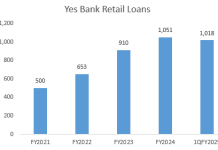

Business Heads Kotak 811

Source: Kotak Mahindra Bank 811 Presentation

The business media dutifully heralded the entry of the Kotak scion.

The Economic Times even titled its article “Long-term succession planning. Jay Kotak is being readied for top role at Kotak Mahindra Bank.”

For good measure the official bank spokesperson was cited stating, Jay’s progress “will continue to be based on merit.”

The media and the attendees were oblivious to the elephant in the room, namely, how was a 32-year old with an MBA degree from Harvard University and a mere three years of work experience was selected as a business co-head in a bank valued at $48.7 billion.

In banks, equity doesn’t come with divine rights

The media and sell-side research, the ostensible sentinels of the public and non-founder shareholder interests, seem to believe that since children of founders tend to be treated as natural successors in non-bank companies, the same norms should be observed in banks. This is not to say that the appointment of family members is appropriate in publicly held non-financial firms, just that it is even less desirable in banks.

In particular, they seem to forget that in a bank even 100% ownership of equity renders the owner a minority stakeholder, as depositors have a significantly larger stake than equity shareholders. Furthermore, on account of the unsecured deposits, high leverage and the pivotal role played by banks in the economy, the banking industry is special, and cannot be compared with other sectors.

Also read: Twenty Years for Uday Kotak as CEO, and the Tailor-Made Exceptions That Allowed It

In private sector banks, especially prominent banks, it is imperative that ownership be separate and distinct from management. When individuals with sizeable shareholding are also CEOs or executive directors (EDs) their interest may conflict with the bank’s interest resulting in mis-management and the failure of the bank as was seen with Ramesh Gelli at the erstwhile Global Trust Bank and recently with Rana Kapoor at Yes Bank.

To prevent promoters from unduly influencing a bank’s operations, the Reserve Bank of India mandated that the promoter stake in a private sector bank be brought down to 15% within 12 years of operation but made a special concession to Uday Kotak to keep it at 26%. After giving the exemption to Uday Kotak, the RBI in November 2021 revised the maximum promoter holding to 26% for all private sector banks.

To curtail the influence of CEOs and executive directors the RBI also mandated that promoter/major shareholder CEOs and EDs have a maximum tenure of 12 years extended by special permission from the regulator to 15 years with an age limit of 70 years. Professional CEOs’ tenure was also capped at 15 years with a similar age limit of 70 years. It is indeed unfortunate that RBI was unable or unwilling to implement this basic principle in Kotak Mahindra Bank, and Uday Kotak was allowed tenure as CEO for nearly 20 years.

By publicly announcing the anointment of 32-year-old Jay Kotak as co-business head, the 63-year-old Uday Kotak is preparing the climate for possible hereditary succession, albeit with a time lag, at KMB.

The critical issue in Jay Kotak’s appointment as co-head of the 811 initiative is what criteria were selected to determine Jay’s suitability for the post. One understands that new digital ventures are set-up in banks as incubators and are staffed by youngsters but there is no explanation to KMB stakeholders why Jay was the most suitable candidate amongst many youngsters for the post, apart from having Kotak as his last name.

Such a lack of clarity highlights a serious issue in KMB on how business heads are selected in such important posts and what is the role of the Nominations and Remuneration Committee (NRC) chaired by Farida Khambata and has as its member, Prakash Apte, the chairman of the board.

There is a marked difference between the profile of the 32-year-old Jay and that of the 47-year-old Manish Agarwal. The latter has 17 years’ bank experience, according to his LinkedIn profile and launched the 811 project in April 2015 and was solely in charge of it from March 2017 till January 2021. As if to justify Jay’s selection, the bank’s presentation states that the average age of the 811 team (excluding call centre and sales) is 32.8 years, but the average age of the 16 key 811 team members highlighted in the presentation is higher, at 38.9 years.

Manish Agarwal. Photo: YouTube screengrab

The order of appearance of the speakers at the function is also very revealing. After Uday Kotak and Shanti Ekambaram spoke, it was Jay who preceded (21:07 in video link) the more experienced Manish Agarwal (29:00) to enlighten the audience on the 811 initiative. During the question and answer session, Jay referred to Uday Kotak as “Dad” (54:33). This could either be attributed to his immaturity or to the reality that KMB is the Kotak family jagir.

The bank took the required approval from KMB shareholders for granting Jay Kotak’s compensation, as he was a related party to the CEO. However, the explanation to shareholders in the notice dated July 26, 2021, did not mention that he had been appointed as a co-business head.

Source: Kotak Mahindra Bank

This analyst sent a questionnaire to Kotak Mahindra Bank enquiring about the selection process for identifying a co-business leader for 811 and how many candidates were shortlisted for the role and on what basis Jay Kotak was identified by Shanti Ekambaram. The questionnaire also enquired about the average age and work experience of the bank’s other business heads. The bank declined to respond to or acknowledge any of the queries. Pertinently, this analyst was not even invited for the analysts’ meet.

The fact that a 32-year-old individual with three years’ relevant experience was selected as a co-business head, and that the bank organised a function to announce the decision taken more than a year earlier, indicates a fast-track promotion system is exclusively available for the son of Uday Kotak. This is then rubber-stamped by the board of directors. The bank’s statement that future progress within the firm will be determined on “merit” lacks conviction when Jay’s appointment as co-business head smacks of nepotism.

In the old private sector banks – those established prior to 1991 – there is one instance of a bank selecting a son with a time lag to replace the father, as was the case with City Union Bank (market valuation of US$ 1.3 billion) and its current CEO, N. Kamakodi.

However, with the Reserve Bank of India capping founders’ shareholding and emphasising diverse ownership, the new private sector banks, particularly the prominent banks, should desist from getting their offspring into banks and fast-tracking their promotion. If founders like Uday Kotak are allowed to promote such a culture, a dangerous precedent will be set wherein existing CEOs will influence servile boards to induct their children or relatives and rapidly promote them to critical positions, so as to ensure succession is kept within the family.

The Indian private sector banking system will then resemble a jagir.