The legal battle concerns the RBI’s instructions to Kotak Mahindra Bank to reduce the promoter holding, and the bank’s sharp practices while appearing to comply.

MUMBAI, Maharashtra—A royal legal battle has been going on between Kotak Mahindra Bank (KMB) and the banking regulator, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), in the Bombay High Court. The next hearing is now scheduled for January 9, 2020. It is likely that both parties may request for a mutually agreed earlier date. The battle concerns the RBI’s instructions to KMB to reduce the promoter holding, and KMB’s sharp practices while appearing to comply. The heat of the battle is reflected in the sharpness of the language used.

In the latest phase of this more than a decade-long drama, the RBI required KMB to bring down its promoter holding to 20 percent or below. On August 2, 2018, KMB threw a bombshell: it announced an issue of Rs 500 crore of Perpetual Non-Cumulative Preference Shares (PNCPS), effectively a form of debt which carries no voting rights. With this, the promoter holding came down to 19.7 percent of paid-up capital, but promoter control is not reduced at all. This defeated the spirit of the RBI regulation, which was to diversify ownership and control.

So far the focus of the discussion by the press and analysts has been on whether the regulator has the powers to compel a promoter to reduce shareholding in a bank. What has received far less attention is the language used by the RBI in describing KMB’s professional conduct.

Normally, the central bank is extremely careful and selective in the words it puts on record, as their interpretation can have a significant impact on the markets and the financial system. Hence the language used by the RBI in its confidential correspondence with KMB, and the subsequent affidavit filed in the Bombay High Court in its reply to the bank’s writ petition is highly relevant and significant for the stakeholders (especially shareholders) of the bank, with respect to the continuance of Uday Kotak, the promoter-CEO and Dipak Gupta, the joint managing director of KMB.

Sudarshan Sen, the then executive director (since retired), RBI, in a letter dated August 13, 2018 to Dipak Gupta, joint managing director, KMB, rejected the bank’s claim that the issue of PNCPS would reduce the promoter’s shareholding. Referring to the bank’s failure to keep the regulator informed on how it planned to reduce the promoter’s stake, Sen said, (all italics are in the original documents).

“However, the bank did not care to apprise Reserve Bank of these developments, thus going back on the assurance given in your letter of March 26. We were informed of the PNCPS issue only after it was completed.We have taken serious exception to this, which amounts to wilful non-disclosure sought by the Reserve Bank.”

In para 10 in its reply dated February 8, 2019, to KMB’s Writ Petition, the RBI states,

“… [KMB has] made several wilful misrepresentations of fact and raised arguments wholly irrelevant to the real matters in issues in order to obfuscate the latter. The Petitioners have by such misrepresentation, clinically singled out unrelated issues, attempting to portray an atmosphere of instability in the financial regulatory systems of the RBI. I say that the Petitioners are also guilty of suppressio veri and suggestio falsi.”

In para 135 of its reply, the RBI explains to the court how KMB informed the RBI of the issuance of PNCPS and states,

“…It is submitted that the Petitioner bank is well aware that the Department of Banking Regulation [DBR or erstwhile DBOD] is the Department which handles the issuance of licenses, operations of banks, dilution of promoters’ shareholding etc. Knowing fully that DBR of RBI is the Department with whom the Petitioner is in constant touch for the last 14 years, it would have been that Department which ought to have been consulted. However, Petitioner No. 1, with mala fide intent sent a mail on August 2, 2018 at 9:47 AM to another officer of the RBI who is not involved with the work relating to DBR of RBI. A copy of the mail sent to Shri R K Moria, General Manager is annexed as Exhibit “Y”. This act of the Petitioner bank clearly establishes how it tried to take the Regulator for a ride and the conduct of the Petitioner bank amply demonstrates the scant regard it has for the statutory regulations stipulated by the RBI.”

The strong language used by the banking regulator to describe the conduct of a regulated entity (now in the public domain thanks to TheWire.in) not only displays the regulator’s extreme displeasure at the bank, but also has severe legal ramifications. Wilful non-disclosure to the banking regulator is a very serious offence, and in the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 (BRA) it is treated as a criminal offence. Indeed Section 46(1) of the BRA states,

“(1) Whoever in any return, balance-sheet or other document 1[or in any information required or furnished] by or under or for the purposes of any provision of this Act, wilfully makes a statement which is false in any material particular, knowing it to be false, or wilfully omits to make a material statement, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years 2[or with fine, which may extend to one crore rupees or with both].”

Normally, the RBI does not invoke Section 46(1) of the BRA when entities provide the regulator with a false statement or withhold important information, as it has to prove that such conduct by the bank was “wilful”. However, in the correspondence addressed to the bank and the subsequent affidavit filed by the RBI in its reply to KMB’s writ petition, the RBI has specifically not only used the word “wilful” but has accused the bank of being “mala fide” i.e the intent to deceive and has said that the bank is guilty of “suppressio veri and suggestio falsi” (the suppression of truth is the suggestion of falsehood). The RBI has also accused KMB of undermining banking regulations and of taking the “regulator for a ride.”

The public and shareholders must realise that this dispute is not between two commercial entities, but between the banking regulator armed with punitive powers and an entity which it regulates. That a banking regulator has consciously decided to use such language to describe a bank’s conduct is extremely serious.

The banking industry is based on trust, as it raises unsecured liquid public savings and channelizes the same into less liquid assets such as loans to economic actors; it also has high leverage and plays a critical role in the payments process. That is the reason why the industry is so heavily regulated. Promoters and senior executives therefore have to be of impeccable integrity and have to be and more importantly perceived to be above suspicion. Senior bank executives, especially CEOs, cannot afford to have their reputations tarnished in a court, least of all by the banking regulator, which has the status of a quasi-judicial body which is mandated to regulate banks.

- RBI Tried To Bury Details Of Demonetisation Advice That Modi Ignored, I Fought Them With RTI

- RBI Board Was Not Convinced About Demonetisation, RTI Reply Shows

- RBI Cuts Repo Rate By 25 Basis Points

If the Bombay High Court favours the RBI in its judgement in this dispute, it would appear that the latter is empowered to invoke Section 46(1) on Uday Kotak, the CEO and Dipak Gupta, the joint managing director of the bank, as it has specifically used the word, “wilful” to describe the bank’s conduct. Even if the RBI is not confident of proving “wilful” in a court of law, how will it consider individuals whom it has described in such strong language to be ‘fit and proper’ to continue as promoters and/or senior executives in a bank it regulates? The RBI’s own credibility would be severely undermined if it were to allow such individuals to continue in their posts after having accused them of mala fide intent, providing wilful misinformation, which is a criminal offence, and of undermining banking regulation, which is a key objective of a central bank.

It is ironic for Uday Kotak’s conduct to be the subject of such language. After all, the capital market regulator, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) had selected him to chair the prestigious Committee on Corporate Governance which submitted its report in October 2017. A year later, the government thought it fit to appoint him as chairman of the IL&FS board when it decided to remove the earlier IL&FS board for mismanagement. That the banking regulator should describe KMB’s conduct in such harsh language thoroughly exposes an iconic figure in India’s corporate and financial sector.

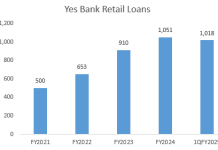

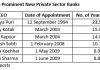

In the case of Axis Bank and Yes Bank, where, despite the financial accounts being questioned by the regulator and other serious corporate governance and mismanagement issues, the boards rewarded their CEOs with another term, the RBI shot down these extensions. In both cases, the RBI waited for the terms of the CEOs to expire, and then took the required action. Similarly, it is apparent that the board of directors of KMB fully supports the action taken by the bank against the RBI. The terms of both Uday Kotak and Dipak Gupta were renewed for another 3 years, from January 1, 2018 till December 31, 2020. If the RBI does not take action prior to their term ending, it remains to be seen whether it will permit another term for individuals whom it has accused of “wilful non-disclosure”, “mala fide intent” and taking the “regulator for a ride.”

Hemindra Hazari is an independent banking and financial sector analyst.