By

Hemindra Kishen Hazari

Rabindra Kishen Hazari Jr. edited and contributed to this article

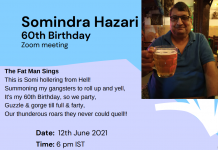

We lost our father, Rabindra Kishen Hazari, in 1986, when I was in my final year (TYBA) in St. Xavier’s College, Bombay. I was just short of being 21 years old. The suddenness of Dad’s death, (he was only 54), was repeated 35 years later when on Holi, 29th March 2021, Yama embraced my elder brother, Somindra Kishen Hazari, (“Sona” to his family and “Somi” to his friends). Sona was 59 years old.

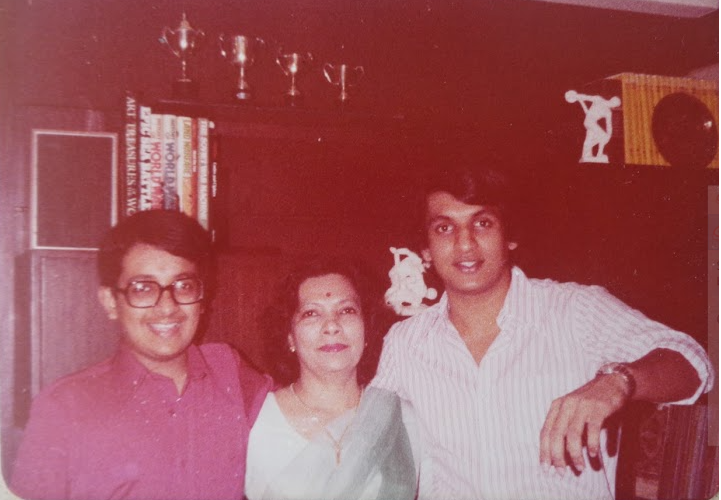

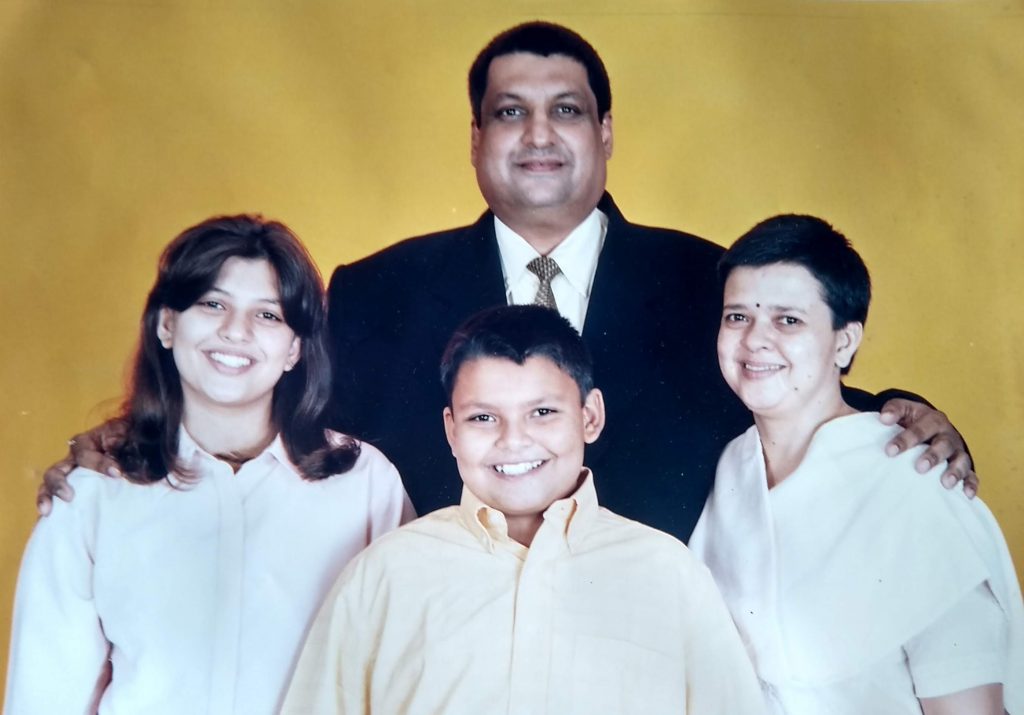

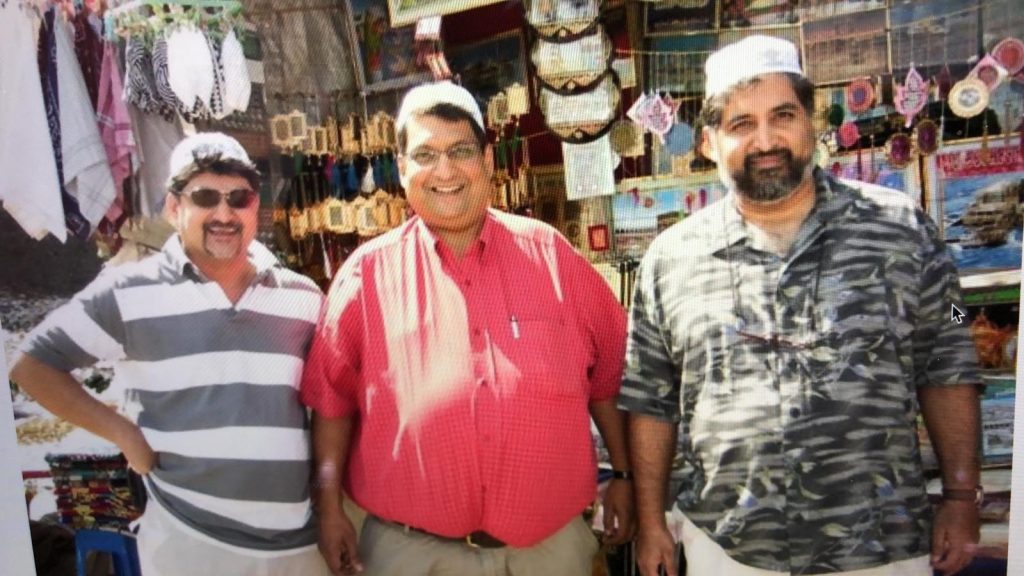

My eldest brother, Rabindra Kishen Hazari Jr, Ravi, (or “Vicky” as we call him at home), wrote a moving tribute to Sona, while Sona’s son, Somindra Kishen Hazari Jr., penned an emotional poem on his flight from Toronto to India. Sunil Khanna, (“Kheru”), Sona’s schoolmate, modified the Cathedral and John Connon school song to a rousing ballad in Sona’s memory. Sona leaves a painful void in our lives and is survived by our mother, Saroj, wife, Varanika, daughter, Shonali, son, Somi Jr., and innumerable friends and relatives, who are all shocked at his abrupt departure.

In 1964, when he was less than three years old, Sona miraculously survived a burst appendix, with gangrene ravaging his small body resulting in massive surgical wounds which erased his navel with horrific scars which covered his abdomen. Sona, lacked an inner stomach wall, and hence had to wear an abdominal belt throughout his childhood.

My father had warned my eldest brother, Vicky, in his incessant fights with Sona, that he could hit Sona anywhere but never in his stomach. My two elder brothers were notorious fighters. They fought constantly. They fought in our home, in the homes of our relatives and friends, in parks and playgrounds and just about everywhere. At home, chairs were smashed as they ripped into each other. My mother would scream in panic but my father, puffing away at his pipe, enjoyed the fisticuffs, egging both sons on, interfering only when the furniture was at risk of getting damaged. Only then, would Dad swiftly stop the fight.

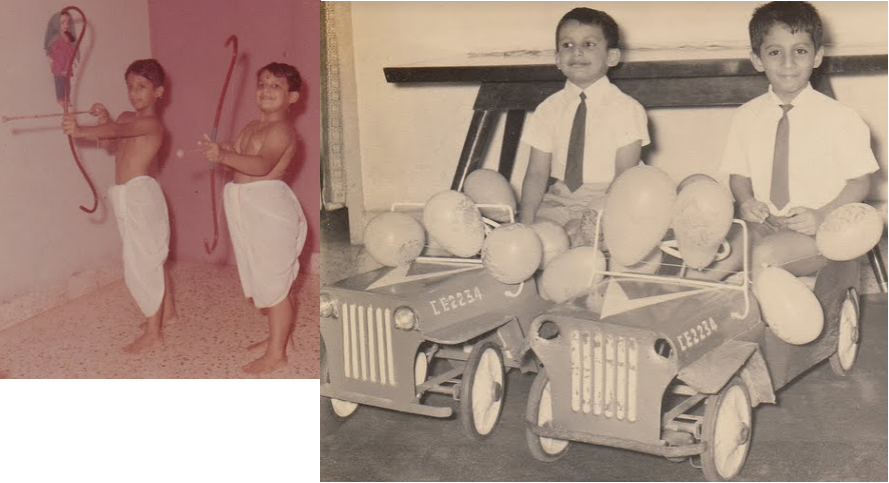

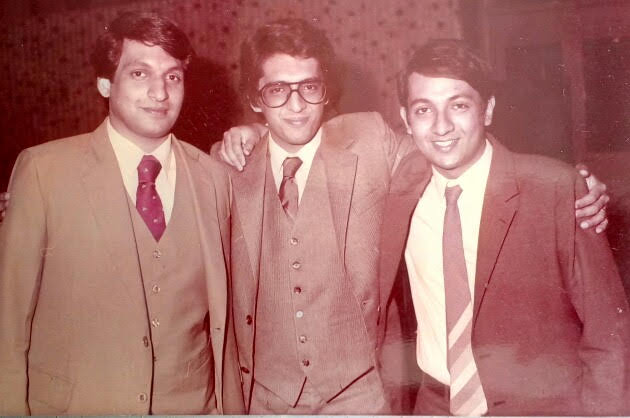

My elder brothers, (two years separated them), were called “Laurel and Hardy”. Vicky was slim, supple and wiry while Sona was always big and heavy like Yogi Bear. Looking at the pair, it appeared that Vicky never stood a chance. Sona’s fighting strategy was to knock Vicky to the ground and then simply squash him by sitting on him. In contrast, Vicky kept dancing out of reach, hitting Sona with fast, vicious punches and kicks using his skill as a gymnast combined with a street fighter’s cunning. In all the bloody fights I witnessed, the honours were even with Vicky having the edge.

When Vicky and Sona were not fighting each other, they ganged up and thrashed everybody else. They soon became notorious as “the Hazardous Hazaris”, an accolade which they mumbled proudly with puffed chests and bloody noses.

As the age gap between Sona and me was 4 ½ years, my physical fights were restricted to Sona and never with Vicky. All my fights with Sona were completely one-sided and they all ended with me running wailing to my mother for protection.

Sona was famous for his hilarious one-liners. I was the perpetual victim of Sona’s jokes and taunts. Once, when I had a particularly painful abscess on my backside, which made sitting very painful, Sona, gleefully introduced me to all and sundry as “the boy with a boil on his bum!”. My anguish, was Sona’s delight, as Sona liked nothing better than roaring with laughter at his own jokes.

Sona’s fond nicknames for me were, “Slave” and “Dog”. I retaliated by calling him “Pig”. Sona was rather porcine in appearance and habit; as hygiene and cleanliness were never Sona’s strong points. Visiting relatives were aghast at our terms of endearment for one another. They sternly coached us to address the elder brother with proper respect as “Bhaiya”. This made both my elder brothers hoot with horror as they vehemently objected at being confused with “Doodhwala bhaiyas”; the Bombaywala’s derisive nickname for men from the Cow belt.

One bright summer morning, my mother discovered some pictorial magazines hidden in my brothers’ room. The treasured magazines were, of course, promptly confiscated by an apoplectic Mamasan. Mum flipped out and screamed herself hoarse ending with the dreaded threat, “I shall speak to your father about this.”

Dad, though usually quite lovable, packed a wallop in his open-handed slap which was destined for your face. Just when you thought that the first slap was bad enough, he followed through with a terrific backhand smash. Dad rarely slapped only once but was a combo slapper with a formidable forehand-backhand combination.

The next morning, both my brothers sat silently at the breakfast table, glumly watching Dad sip his tea and peruse the Economic Times, fatalistically awaiting Dad’s celebrated combo slaps. After carefully noting that Mum had exited the dining room, Dad looked up and said, “Your mother has informed me of your reading habits. She has handed me your magazines. In future, when you get such magazines, kindly extend the courtesy of promptly sharing them with me.”

Thereafter, as per the Concordat arrived at between father and sons, we faithfully shared with Dad whatever magazines we got. Likewise, whenever Dad returned from his foreign trips, he dutifully handed over the latest magazines for his boys. In school, Dad became a celebrity as Sona and I became the librarians of our respective classes for the treasured, well-thumbed issues which Dad so thoughtfully provided. In the years to come, whenever we recalled those lovely ladies, we sang hallelujahs of praise to Dad for spurring us on in the pursuit of happiness.

Hailing from a hard core carnivorous family, my mother, a Tulu speaking Mangalorean, who loved chicken and fish, and Dad, a renegade Kashmiri Pandit, who relished mutton, beef and pork, our world revolved around non vegetarian food.

Sona, ever the Glorious Glutton, was obsessed with food. Always hungry, with the size, appetite and temperament of Bhim, Sona jealously watched my mother doling out portions of meat or chicken at mealtimes, when he would erupt with rage, accusing Mum of favouring me, with the choicest pieces of meat. Sona bitterly complained to Mum with all seriousness; “You only believe in odd numbers, 1 and 3; I am the even number 2, so I get treated like your step son”. For several years, Sona caustically reminded me, “As I was served only bones, I became tough and strong, while you are soft and weak as you were fed the choicest cuts of meat ! ”

Sona, despite wearing an abdominal belt, secretly enrolled for boxing in school without informing our parents. Fortunately, he did not suffer any injury which would have been catastrophic as he did not have any abdominal wall. In the 8th standard, Sona underwent a major four hour surgery whereby multiple hernias were corrected and his stomach muscles were reconstructed. Sona no longer had to wear an abdominal belt.

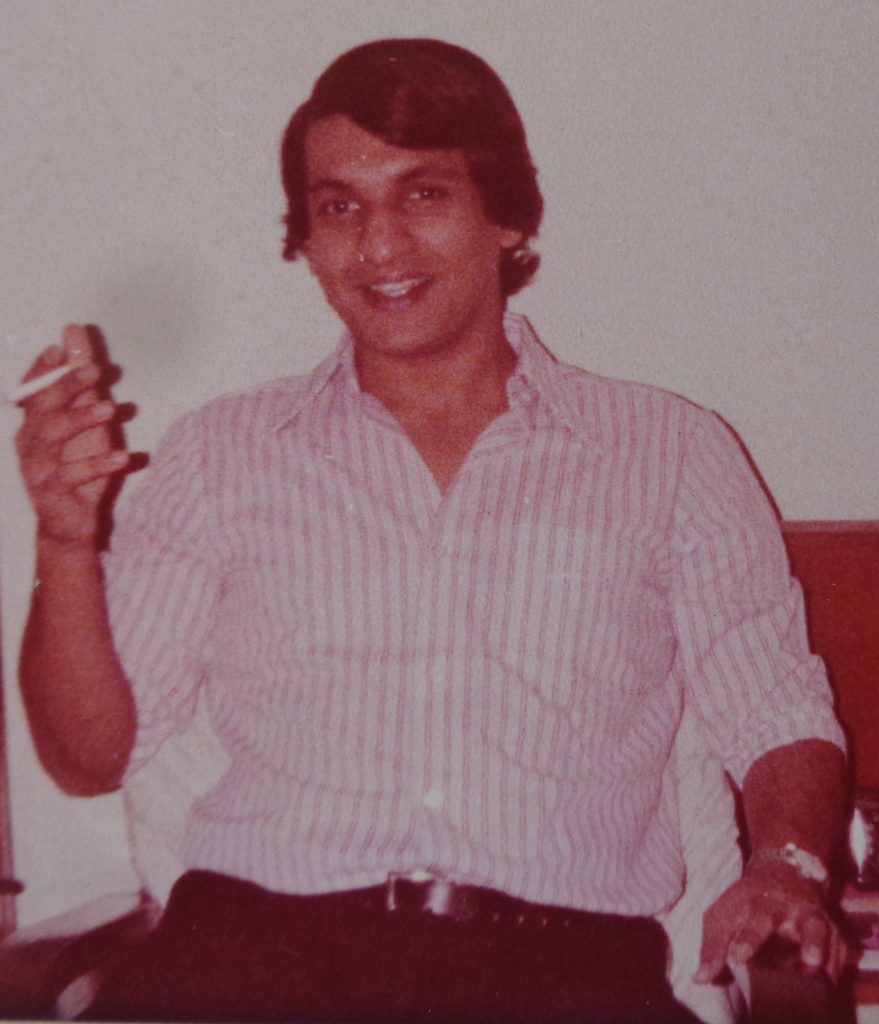

The surgery magically transformed Sona who lost his big paunch and he could now play rough games with impunity. Sona was now dashingly handsome, with a physique resembling Michaelangelo’s David and he was constantly surrounded by a bevy of girls who fawned all over him. Sona’s Harem was Sona’s Pride and Brothers’ Envy.

While Sona and I regularly fought and Ravi occasionally ribbed me, the rules were clear: only my brothers and nobody else could tease me. No other boys, senior or bigger than me, dared bully me as my brothers suddenly descended on them with fraternal fury. However, when it came to boys of my own age and size, they did not interfere. Instead, they coached me in boxing, in which they both excelled. My brothers taught me to fight well and hard with no quarter asked nor given. Non-violence was never an option. The lessons in fisticuffs came handy. Decades later, when I tread the lonely path of exposing the powerful, the corrupt, the greedy, and the incompetent, in India’s revered financial world, I was never really alone, as in my corner my guardian brothers always protected my back. Taking on the high, the mighty and the privileged never deterred us. Whenever the occasion demanded, we stood up to be counted and fought the good fight. We were, after all, the Hazardous Hazaris.

In Cathedral School in those days, boxing started in the 7th standard. The boxing ring was traditionally erected in the senior school quadrangle with screaming students lining the balconies on three sides looking down on the ring, reminiscent of the blood thirsty Roman mobs of the gladiatorial arenas.

When I entered the 7th standard, I jokingly told my brothers that I will not box. My brothers were appalled. Vicky sternly rebuked me stating, “Your real education is not in the classroom. It is when you are blooded in the boxing ring and are trampled and torn on the Rugby field.”

And so it was that I was well blooded in the Inter-House Boxing Tournament. Sona was in my corner as my second. Vicky had already passed out of school. In the first round, I was hammered hard; my face being a mess of blood, sweat and saliva. As the bell sounded for the end of the first round, I returned to my corner, bloodied, bruised and in shock. In those thirty seconds between rounds, Sona pumped me with courage and cunning, and in the next two rounds, I gave as good as I got, eventually losing narrowly in a closely fought fight. Later, Sona counselled me, “You panicked initially when you got hit. It is only when you get hit, that you learn. You learnt. Don’t worry. The lessons of the Ring; are the lessons of life.”

Years later, when I left Cathedral School for St Xavier’s College, I returned to the boxing ring in our school quadrangle to cheer my former classmates. The school boxing captain, Arjun Erry, a fine technical boxer, was about to commence his bout. Knowing how butterflies flutter furiously in a boxer’s stomach before the bell sounds, I sauntered to his corner and said “Erry…When the bell rings, you hit first, you hit hard and you keep hitting.” That’s what Erry did and that’s how he won his bout. These were the lessons of the Ring; learnt hard and well with blackened eyes and bloodied lips, which were to guide me as a beacon in my future career as a research analyst.

Sona had a heavy hand and boy did I know it well. My last physical fight with Sona was when I was in Junior College. I took the family car, a classic 1961 FIAT 1100, BMF 7658, which was the love of Sona’s life, without informing Sona. Worse, I came back late and on seeing Sona frothing at missing his date, I made the cardinal mistake of laughing in his face. Sona shrieked with rage and rushed at me like an maddened bull elephant in musth. I thought I stood a chance as I was at the peak of my fitness but then so was he. Sona’s right hook slammed into my jaw. My head snapped back bouncing off the wall behind me and I was stunned, Dad sprang to my defence, lashing Sona with his celebrated forehand-backhand combo slaps, restraining Sona from administering me the coup de grace.

Sona continued with boxing in Sydenham College participating in the Bombay University Inter-College Boxing Tournament. Vicky was very excited and rushed back from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi to coach Sona. In the final bout, Sona out fought his opponent to be crowned the heavy weight boxing champion of Bombay University. The following year, an over confident Sona did not bother to practice at all. Instead, Sona kept preening himself as Sylvester Stallone in “Rocky”, whose lisp he faithfully mimicked along with the dark aviator googles which he tirelessly wore all day and all night. Vicky could not come from JNU to act as Sona’s second. In a keenly contested fight, Sona lost his heavy weight boxing crown but broke his opponent’s nose.

While I gave up fisticuffs after my last scrap with Sona, both my elder brothers, even in their late-fifties, remained incorrigible, gleefully wading into fights with fists flying, baying with fury, the blood lust burning bright in their eyes.

In school and college, Sona was a party animal, rarely to be seen at home. It is not for nothing that Amma, our quick-witted maternal grandmother, nicknamed Sona as “Road Inspector.” Sona’s constant partying and being out late with friends annoyed my mother no end. One late morning, Mum angrily inquired, “What time did you come home?”

Pat came Sona’s reply, “I was home early.”

“What nonsense Sona, don’t lie to me. I was up till past midnight and you had not come home.”

Sona smoothly replied, “I am not lying Mama. I came home early…early in the morning.”

Marriage changeth the Man or so they say. For Sona, marriage meant acquiring a wife who was his unwitting accomplice. Post marriage, Sona went on an eating binge whereby his weight peaked at 215 kilos. Sona, however, remained surprisingly quick on his feet During a stay at the Taj Malabar in Cochin, with his petite Anglo-Indian wife, Varanika, Sona was in the loo, performing lustily on the Throne, when there was a thunderous crack followed by a roar of rage from Sona. Alarmed, Varanika rushed into the loo to find that the western commode had shattered with jagged shards intermingled with crap all over the floor. Sona was miraculously unhurt but was howling with rage. While Varanika stood thunderstruck wondering how to clean up the foul mess, Sona quickly cleaned himself and rushed out. The next thing she knew was that the hotel manager was in the room with a formally dressed Sona was hollering at him. Pointing to Varanika, he said, “Look at her size. I can understand if it had been me on the pot, but no, it was her on the pot, and yet your damn pot broke!”

There was something obviously wrong with the quality of the commodes at the Taj Malabar. In the span of the next two days, Sona smashed a further two commodes. However, each time he claimed that his dear wife had been perched on the commode when it mysteriously fell to pieces. And hence it came to pass, that Sona earned for his wife the title of “Commode Breaker”.

Based in Madras, Sona was a familiar figure in the South Indian Chambers of Commerce with his extensive business contacts with Sri Lanka, Southeast Asian and European countries. A frequent speaker at events he elaborated on the need for growing trade between India and neighbouring nations.

Sona’s generosity was as wide as his girth which was massive. When I went through difficult times, as I was continually exposing powerful corporate cronies, Sona helped me tide over this tough period. Sona was always there, ever generous with gifts for both Vicky and me, for which Sona never kept tabs. Sona’s visits to Bombay were like the first rains following a drought. He came laden with gifts for family and friends and our home filled with laughter as he regaled us with his latest antics. Sona was an One Man Movie, with his stories projected on a 70 mm screen in Technicolour and Dolby sound. Sona played his role of prankster and Court Jester with full zest; remaining at heart the Honourable Schoolboy who never grew old.

Mum, Vicky and I were knocked out when we heard that Sona had expired on Holi. It was unbelievable. It was not possible that our dear indestructible, ever playful Sona had left us so quietly and so suddenly. How could he leave us so? Numb with disbelief, we left Mum in Bombay, and Vicky and I flew to Madras. There we choked on seeing our beloved Sona entombed in a glass covered refrigerated casket. I recalled how Sona had found humour even in the most sombre of moments. Many years earlier, when accompanied by his langoti friend and fellow prankster, Arun Rao, (aka Rho), they attended the funeral of a colleague lying in an open coffin. As they stooped over the body to pay their last respects, Sona turned to Rho and enquired, “Do you know why cotton is stuffed in his nose?”

When Rho pleaded ignorance, Sona replied, “To stop the smoke from coming out,” as the gentleman was a chain-smoker throughout his life.

Death is not a pretty sight but as I gazed with tear soaked eyes at Sona’s face for the last time, all I could see was the goodness in him for he was my elder brother who loved me fiercely and I too loved him with all my heart

What a lovely write up about Somi! Miss u dear Somi.😭

I miss you Somi.

“… Sona shrieked with rage and rushed at me like an maddened bull elephant in musth.”

Hemu, this was a brilliant obit for Sona. And I thought Ravi’s was great, but yours outdid his. You Hilarious Hazaris are a handful. I’m sure he’s shuddering with laughter at our piece. I remember from Sona decades ago, he was in my sister’s class in school. Lovely chap. Well loved by all.

Hemindra

It is very difficult and painful to go through the void of abrupt departure of a family member. Kindly accept my heartfelt condolences. I pray God to rest the departed soul in eternal peace and give you enough strength to bear this irreparable loss. Time alone will heal the grief. I will say that your beloved brother Mr Somindra is around you through the great memoirs you have of the time spent together which you have covered well in the tribute to him.

I would like to quote a Gita verse here.

न जायते म्रियते वा कदाचि न्नायं भूत्वा भविता वा न भूयः।

अजो नित्यः शाश्वतोऽयं पुराणो न हन्यते हन्यमाने शरीरे।।2.20।।

It (the self) is never born; It never dies; having come into being once, It never ceases to be. Unborn, eternal, abiding and primeval, It is not slain when the body is slain.

I came across your email today.

Zaregaonkar

April 22,2021

Well written, Hemu! You created a vivid account of your memories with Sona.